Good morning, class.

I love making lists. Ever since I started this blog I’ve been anxious to put the list of “50 Books to Read Before You Die” in order, from least favorite all the way up to favorite. I had to read them all first—so here’s a three-years-long dream coming true. I’ve read Every. Single. One.

To be honest, I paid more attention to the very least favorite and the top ten. The middle-ranked books got organized with a little less scrutiny. But I really can’t stand Martin Amis’ Money: A Suicide Note so it’s at the bottom. I wish I could unread it.

| 50. | Money: A Suicide Note by Martin Amis |

| 49. | On the Road by Jack Kerouac |

| 48. | A Bend in the River by V. S. Naipaul |

| 47. | Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe |

| 46. | The Quiet American by Graham Greene |

| 45. | The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri |

| 44. | The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer |

| 43. | Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes |

| 42. | The Stranger by Albert Camus |

| 41. | Frankenstein by Mary Shelley |

| 40. | Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift |

| 39. | The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells |

| 38. | The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain |

| 37. | A Passage to India by E. M. Forster |

| 36. | The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame |

| 35. | The Way We Live Now by Anthony Trollope |

| 34. | The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas |

| 33. | A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens |

| 32. | Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë |

| 31. | Lord of the Flies by William Golding |

| 30. | Memoirs of a Geisha by Arthur Golden |

| 29. | The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde |

| 28. | Moby-Dick by Herman Melville |

| 27. | Brave New World by Aldous Huxley |

| 26. | The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath |

| 25. | Men Without Women by Ernest Hemingway |

| 24. | Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë |

| 23. | The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck |

| 22. | Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy |

| 21. | Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll |

| 20. | Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier |

| 19. | Hamlet by William Shakespeare |

| 18. | Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad |

| 17. | 1984 by George Orwell |

| 16. | The Lord of the Rings Trilogy by J. R. R. Tolkien |

| 15. | One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey |

| 14. | Catch-22 by Joseph Heller |

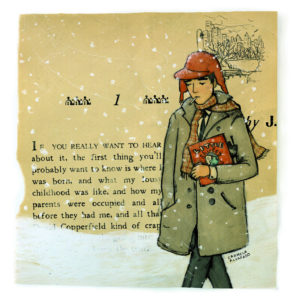

| 13. | The Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger |

| 12. | The Diary of Anne Frank by Anne Frank |

| 11. | Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen |

| 10. | The Color Purple by Alice Walker |

| 9. | Birdsong by Sebastian Faulks |

| 8. | The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Timeby Mark Haddon |

| 7. | His Dark Materials Trilogy by Philip Pullman |

| 6. | The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald |

| 5. | The Bible by Various |

| 4. | Life of Pi by Yann Martel |

| 3. | To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee |

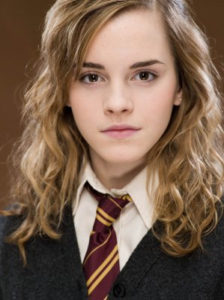

| 2. | Harry Potter Series by J. K. Rowling |

| 1. | Ulysses by James Joyce |

Yes, of course Ulysses is my top pick. I know it’s certainly not everyone’s favorite, I know it’s one of my several biases . . . but I love it anyway.

After writing this list out, I looked back at some of my older posts—looks like I condemned ranking books a few times, making my list here a bit hypocritical. Well, maybe a person can’t compare one book to another in a hierarchical system like this . . . I may pick Ulysses as my favorite, but I can’t just pick it up and read it for fun the same way I can with a Harry Potter book. And, to be fair, while I picked Ulysses for the way it changed my perspective as a reader, and for the way it portrayed love and humanity, it’s not like Harry Potter didn’t do that for me first.

If I have a point, I guess it’s that a book’s meaning to you as a reader will constantly change—and that there are as many books as there are people, and as many complicated feelings about stories as there are relationships.

I’ve got one more blog post planned—I want to share some of my personal reflections about reading all 50 books. Then you can all graduate from Prof. Jeffrey’s class.

Until then,

Prof. Jeffrey

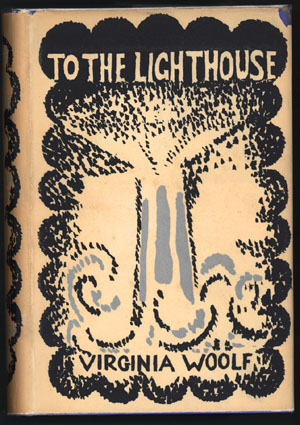

Virginia Woolf is one of those hallmark authors who stand out by reputation alone, regardless of sex as a qualifier, while still being one of the clearer representatives of feminism known in literature. The fact that she has no novel on the 50-books list highlights the fact that so many other women are left off of it, too.

Virginia Woolf is one of those hallmark authors who stand out by reputation alone, regardless of sex as a qualifier, while still being one of the clearer representatives of feminism known in literature. The fact that she has no novel on the 50-books list highlights the fact that so many other women are left off of it, too.

Something I tend to forget about modernism is its obsession with time. Novelists from this period liked to portray the unreliability of time by reorganizing chronological order, speeding up and slowing down the story, and confusing a single moment with an eternity. Virginia Woolf fit right in with these modernists—entire chapters in parts 1 and 3 of To the Lighthouse take place in seconds, while part 2 speeds through ten years in no time at all. The action of parts 1 and 3 is also mostly internal, letting stream-of-consciousness explain characters and their motivations—something modernism all but invented.

Something I tend to forget about modernism is its obsession with time. Novelists from this period liked to portray the unreliability of time by reorganizing chronological order, speeding up and slowing down the story, and confusing a single moment with an eternity. Virginia Woolf fit right in with these modernists—entire chapters in parts 1 and 3 of To the Lighthouse take place in seconds, while part 2 speeds through ten years in no time at all. The action of parts 1 and 3 is also mostly internal, letting stream-of-consciousness explain characters and their motivations—something modernism all but invented.

Good morning, class.

Good morning, class.

These Odyssey references, where the name Ulysses comes from, give the novel it’s epic-ness. The length of this one day is impressive, so filled with detail that it overflows at the seams, and it still doesn’t capture every single moment of the day. The ancient has been updated to match advances in technology and societal evolution, but it still meets the same archetypes it’s known for.

These Odyssey references, where the name Ulysses comes from, give the novel it’s epic-ness. The length of this one day is impressive, so filled with detail that it overflows at the seams, and it still doesn’t capture every single moment of the day. The ancient has been updated to match advances in technology and societal evolution, but it still meets the same archetypes it’s known for.

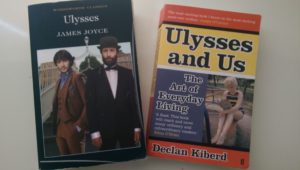

If you are going to try it, and you don’t have a literary professional standing nearby at all times, you might try reading a guidebook along with it—I recommend Ulysses and Us: The Art of Everyday Living by Declan Kiberd. It’s pretty focused on understanding the intentions behind the novel, and it helped me find the love within Ulysses. I also recommend any and all online resources—a summary won’t replace the novel, but it will help you understand what on earth is happening.

If you are going to try it, and you don’t have a literary professional standing nearby at all times, you might try reading a guidebook along with it—I recommend Ulysses and Us: The Art of Everyday Living by Declan Kiberd. It’s pretty focused on understanding the intentions behind the novel, and it helped me find the love within Ulysses. I also recommend any and all online resources—a summary won’t replace the novel, but it will help you understand what on earth is happening.

Recent Comments