Good morning, class.

I had the pleasure of reading Alice Walker’s The Color Purple for the first time, knowing only that it is very controversial. But I had no idea it was so beautiful.

It tells the story of two Southern African-American sisters separated for years, keeping in touch through a series of letters to each other and to God. Celie, who is stuck in cycles of abuse and violence, finds love with another woman and transforms her life. Nettie has been sent as a missionary to Africa, where she discovers culture and history that change her worldview forever. Celie and Nettie remain in love with each other across time and distance.

The 1982 novel was adapted into film by Steven Spielberg in 1985, and it debuted as a musical in 2004.

Lovely Hoffman as Celie in the musical adaptation of The Color Purple

The novel may be more popular because of its controversy. It doesn’t censor itself—it is explicit with elements of abuse and sex. It brazenly portrays adultery and homosexuality. Its language and content are perfect catalysts for court cases and a quick book banning.

To be clear, this particular quality is in the novel’s favor. It holds back nothing. In my professional opinion, censorship that reacts directly to elements like adultery and homosexuality is indicative of a culture that knows what’s “best” for it’s mindless population. It is also a direct form of discrimination.

But the politics aren’t as important to me as the art. I’ve been around the literary block enough times to see that when a novel tosses the moral rule-book out the window, it lets the story tell something more beautiful. The choice to disregard right and wrong help us question right and wrong, and give us the ability to decide for ourselves what right and wrong mean…rather than adhering to the ideas of someone else. The R-rated movies, the TV-MA programs, and the books constantly challenged by censorship laws are the ones that help us evolve.

That’s what The Color Purple has to offer—a more beautiful story, a question about traditional rules and morals, and a chance to evolve. Celie’s discovery of her own sexuality matches Nettie’s discovery of African history and heritage. Though their physical journeys are different, their spiritual journeys are parallel.

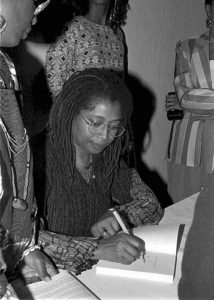

Author Alice Walker

If I have to pick a favorite moment in their respective journeys, its their growth in their ideas about God. They both begin to see God in a way that flaunts tradition, dismissing the image of the larger, bearded white man, dressed in white, standing at the gates of heaven. Maybe God is less white, and less man. Maybe God is everything: the trees, the flowers, the earth, the universe. God isn’t restricted by the confines of Biblical imagery.

The novel also works in a way that un-writes history. These characters live in the past, and they exist on the fringes of society. No one is paying them attention. As they make discoveries, those discoveries are forgotten by the larger public because these characters’ opinions don’t matter to anyone else.

That’s part of the brilliance of the novel—Alice Walker shows us that characters like these existed then and exist now, and will continue to exist. Their story matters. They are human beings, minority or not. And in a world that seems to constantly forget facts like that, it’s important to say it again here.

Next, I’ll be reading Graham Greene’s The Quiet American. I’m excited because I know it predicted many elements of the Vietnam conflict in American history…any novel that sees where the world is headed, even when the rest of the world can’t, earns thumbs up from me.

Until next time,

Prof. Jeffrey

0 Comments

1 Pingback