We’re at the end, class!

I’m not dying, or anything. But I promised myself at the beginning of this that I wouldn’t push this blog too far. I wouldn’t let it be one of those blogs that posted a lot at once, tapered off into a few posts a year, and died out from age or boredom. (If anyone thinks to look back at the posting dates of each one of my posts, you’ll notice a remarkable consistency.)

Which means there’s a finale to this saga. I read and reviewed the 50 Books to Read Before You Die, according to a bookmark. Just a few final remarks, and that’s all, folks.

I liked most of them. I loved many of them. There were a few I couldn’t stand, and I’m getting rid of those (to leave room on my bookshelf for better books). They all left an impression . . . they all gave me something to think about, something to chew on. Reading each one gave me a world to explore or a new perspective to consider. That’s what books are for.

Several of them gave me clues about how to be a better writer. This list is full to the brim of storytelling techniques, fascinating characters, and hilarious puns. I think all the great storytellers and artists copy from the greats, and this list featured some of the greatest stories of all time—so I’ve got a storytelling repertoire that will continue to inspire before I expire.

I keep coming back to why I chose to do this, and there’s one very obvious answer. I’d just graduated college. I loved college, and more importantly, I loved going to class. I love reading books and then talking about them. We just read this amazing chapter in this book I love, I can’t miss class! The professor’s going to break it apart, show me the little pieces that I missed—then I’ll love it even more!! That’s me. So what’s a man to do after graduation, when there are no more classes, no more professors, no more books and discussions? He starts a blog, of course.

I did this because I’d done nothing but read the assigned reading for the past four years. I wanted to dare myself into reading “literature” on my own. This was my way of making a real life class for myself, a series of self-assigned readings that any professor of a grade-A-geek would be proud of. And I did it for myself—not to show off my limited knowledge to people that know me, but to make myself better as a reader, writer, and storyteller, through the magic of the internet.

But I don’t stoop to think that this almost-three-year task made me a better person. I didn’t expect it would, because a better reader/writer/storyteller is not a better person. (If that sounds like too obvious a statement, I can assure you, that’s something I had to learn, and it’s something several fully grown adults still don’t know.)

It’s like the difference between living and reading about living. Some writers will tell you that the story is all that matters, but that only applies to stories, not to life. Stories serve many purposes—relief, connection, understanding, entertainment, discovery, motivation—but the one thing a story can’t do is replace living. Stories are reflections of life, and so is everything from history to art, from the greatest movie ever to a good joke. The reflections take us where we cannot go, far and wide around the Earth, back in time and forward to the future, and life still waits for us when we return.

No, this didn’t make me a better person. I learned a lot, though. If I use all I learned to not only tell better stories, but live a better life, then I’ll become a better person, I hope. That’s why the blogging is done, at least for now—I’m done with this chapter of my life-book, and if I stick around for too long, I might not get to the rest.

So keep reading. Then go live with what you learned.

Prof. Jeffrey

I’ve been comparing

I’ve been comparing

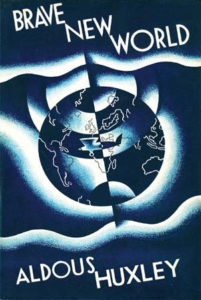

The society of Brave New World runs on a set of rules that everyone happily follows; for instance, solitary actions are as prohibited as possible, and in sexual terms, everyone belongs to everyone else. Extreme emotions have been all but eradicated with removal of the family unit, genetic modification, psychological conditioning, and a drug called soma. Without extreme emotions—passion, rage, fear, jealousy, misery—all that’s left is a mellow contentment. Between universal happiness and ideals like truth, beauty, or knowledge, the populace has overwhelmingly chosen happiness.

The society of Brave New World runs on a set of rules that everyone happily follows; for instance, solitary actions are as prohibited as possible, and in sexual terms, everyone belongs to everyone else. Extreme emotions have been all but eradicated with removal of the family unit, genetic modification, psychological conditioning, and a drug called soma. Without extreme emotions—passion, rage, fear, jealousy, misery—all that’s left is a mellow contentment. Between universal happiness and ideals like truth, beauty, or knowledge, the populace has overwhelmingly chosen happiness.

1984 is about a regime holding power and using ideology, propaganda, and torture to subdue threats . . . humanity’s enemy is more powerful than ever, but it’s the same enemy: an upper class with all the power. Brave New World might even be scarier, because there is no enemy. Humanity simply gave up, surrendered to happiness. All the things we like to think make humanity good—art, morality, intelligence, curiosity, passion . . . all replaced by peace. A numbing, terrifying global peace.

1984 is about a regime holding power and using ideology, propaganda, and torture to subdue threats . . . humanity’s enemy is more powerful than ever, but it’s the same enemy: an upper class with all the power. Brave New World might even be scarier, because there is no enemy. Humanity simply gave up, surrendered to happiness. All the things we like to think make humanity good—art, morality, intelligence, curiosity, passion . . . all replaced by peace. A numbing, terrifying global peace.

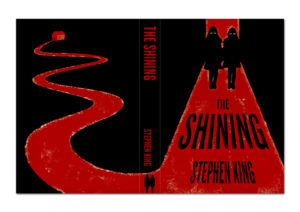

The story: a small, struggling family watches over the Overlook Hotel through the winter, as supernatural forces try to tear them apart. The father’s alcoholism leaves him vulnerable to the violent spirits in the hotel, and he becomes monstrously abusive. His wife tries to protect their little boy, who just happens to have the ability to communicate with the spirits around them—an ability called shining.

The story: a small, struggling family watches over the Overlook Hotel through the winter, as supernatural forces try to tear them apart. The father’s alcoholism leaves him vulnerable to the violent spirits in the hotel, and he becomes monstrously abusive. His wife tries to protect their little boy, who just happens to have the ability to communicate with the spirits around them—an ability called shining.

Good morning class.

Good morning class.

A lot of my time in literature courses at college was spent asking the probing question, “What is literature?” (We’ll get to WHY that’s an important question in a bit.) It seems like a simple enough question, but it always invokes a huge discussion that usually boils down to this: literature is art that uses words and language. It’s also described as a category of art—literature is always art but art is not always literature.

A lot of my time in literature courses at college was spent asking the probing question, “What is literature?” (We’ll get to WHY that’s an important question in a bit.) It seems like a simple enough question, but it always invokes a huge discussion that usually boils down to this: literature is art that uses words and language. It’s also described as a category of art—literature is always art but art is not always literature.

But let’s bring it back down to something resembling sanity. Why do we read? Usually, to learn something. When we read Shakespeare, we want to learn about the characters he’s created and the philosophy he’s trying to sell. When we read a letter or e-mail, it’s to keep up correspondence and to understand their goal or message in sending their note. When we read a magic 8 ball, we want a prediction, whether we believe it or not.

But let’s bring it back down to something resembling sanity. Why do we read? Usually, to learn something. When we read Shakespeare, we want to learn about the characters he’s created and the philosophy he’s trying to sell. When we read a letter or e-mail, it’s to keep up correspondence and to understand their goal or message in sending their note. When we read a magic 8 ball, we want a prediction, whether we believe it or not. I’ve tortured you enough. There is no definite answer to this question, and asking it is more academic “fun” than it is accomplishing ANYTHING. And yet, my follow-up question still stands: why is a question like this important? Don’t worry, it’s a much easier question to answer.

I’ve tortured you enough. There is no definite answer to this question, and asking it is more academic “fun” than it is accomplishing ANYTHING. And yet, my follow-up question still stands: why is a question like this important? Don’t worry, it’s a much easier question to answer.

Recent Comments