Hello again, class.

We’ll have a bit of a history lesson today, and talk about literary periods. Historical context can redefine a piece of literature, and something that’s always helped me with reading older texts is understanding which period of history it came from. The Victorian Era, for example, was the era of Great Britain during the reign of Queen Victoria. I know little bits about Victorian society, belief systems, social stigmas . . . each one increasing my understanding of novels and poems of the time. It’s basic reading strategy any good blog professor should know.

My two favorite periods of literature are Modernism and Postmodernism (which are more like one 2-part period, but I didn’t write the textbooks). More than being the eras of some of my favorite works, I think the majority of the books on the 50-books list could fall in the categories of modern or postmodern literature. That alone makes it worth knowing what these categories mean and how they apply to novels on the list.

(Disclaimer: I am summing up entire textbooks worth of information into a blog post. It’s a LIMITED analysis.)

Modern writer F. Scott Fitzgerald, author of “The Great Gatsby.”

Modern literature doesn’t actually mean “modern” like new or contemporary. It sort of meant that at the time, but that period is about a hundred years old by now. When people talk about modern literature, they’re usually referring to the first half of the 20th century, ending around the same time as the end of WWII. That period of history was, on a worldwide scale, sheer chaos.

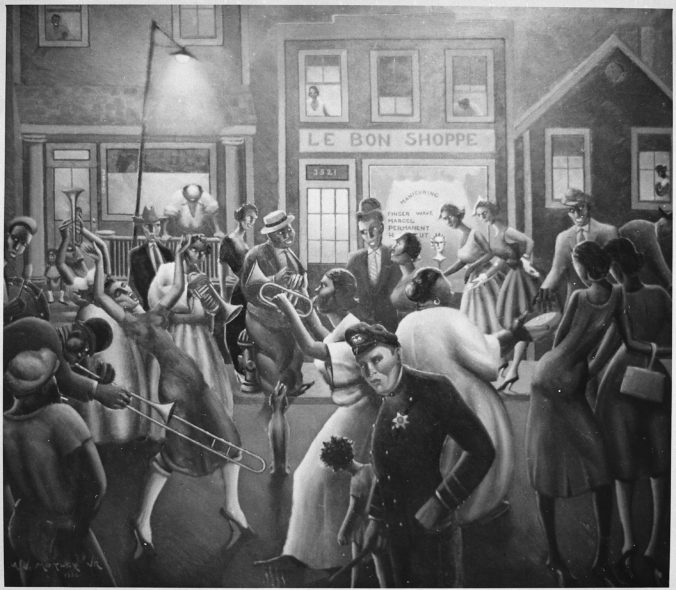

Both World Wars, the Great Depression, political movements for women’s rights, the Harlem Renaissance, introduction of Freud’s theories, the roaring 20’s, advances in technology . . . these are fractions of the chaos of the time. Traditions were breaking down, becoming fragmented copies of the old world. Questions were asked about morality, society, sexuality, religion, government, the future—questions that were never considered before.

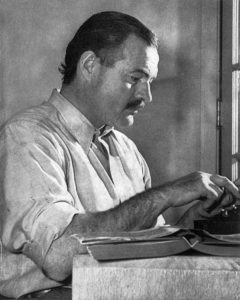

Modern Writer Ernest Hemingway, works including “The Sun Also Rises” and “The Old Man and the Sea.”

The art reflected the chaos. Novels like The Grapes of Wrath and As I Lay Dying were chaotic in the most complicated ways; they broke the rules of grammar and storytelling, and they sacrificed old traditions to make room for greater truths. Poems like T. S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” and W. B. Yeats’ “The Second Coming” broke the rules of poetry and removed the comfort of structure.

The dates are shifty for Modernism, so they are just as shifty for the sequel, Postmodernism. Ending with WWII and working through the Cold War and the later half of the 20th century, the Postmodern Era shares a lot of similarities to Modernism. The chaos of the 50s, 60s, and onward, the continuing breakdown of traditional values, the Vietnam and Korea conflicts, the birth of nuclear power, the Civil Rights movement . . . the chaos continued.

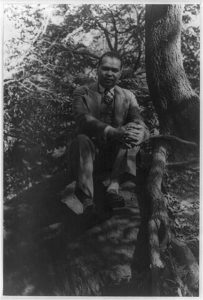

Postmodern poet Allen Ginsberg, author of “Howl.”

But one of the key differences was how the artists responded (which is why it gets a different name in the textbooks). The artists of the modern era were more afraid of the chaos, and the art was used to help them cope with it. But postmodern artists celebrated the chaos; they relished in the collapse of the old and the strangeness of the new.

Novels like The Catcher in the Rye, The Color Purple, and On the Road fall in the postmodern category. These writers took the previous generation’s fear and apprehension and transformed it into a movement that praised the breaking of tradition. Novels like these lived into the chaos of the time.

Postmodern author Margaret Atwood, author of “The Handmaid’s Tale.”

But as I said, the reason I chose these two periods for today’s lesson is not just because they’re my favorite, but because they sum up most of the books on the 50-books list. Before the 20th Century, elements of modern and postmodern literature can be seen popping up among the best of literature. Novels like The Picture of Dorian Gray and Pride and Prejudice and even older pre-novel works like Hamlet and The Canterbury Tales have elements reflecting the chaos: the depths of psychology, the fear of advancing technology, the downfall of conventionality, the inherent wrongness in rules of morality and religion.

Personally, I think all of literature was leading toward the birth of modern works. Questions about race asked by Oroonoko and Robinson Crusoe are answered by literature from the Harlem Renaissance. The heavily structured language of the Victorian Era’s A Christmas Carol and The War of the Worlds led to the deconstruction of language in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Early women writers like Aphra Behn and Jane Austen opened the doors for modern and postmodern writers like Virginia Woolf and Alice Walker. There’s no Ulysses without Dante’s Divine Comedy.

That’s my theory, anyway. And I like it for the same reason I like Ulysses: the “everything-is-connected”-ness of it all. Granted, it’s not a very scholarly theory, but it puts the “story” in “history.”

As I finish up Ulysses, you’ll hear more of this theory—next week is the big one!

Until then, enjoy your week.

Prof. Jeffrey

Overcoming the Monster (that’s, like, the millionth time I’ve mentioned this one—take the hint, it will be on the test)

Overcoming the Monster (that’s, like, the millionth time I’ve mentioned this one—take the hint, it will be on the test) A professor once told me that there are two ways to start a story—either a stranger comes to town, or someone decides to leave. Whatever happens from there changes everything. Somehow, that simple prompt is both challenging and comforting.

A professor once told me that there are two ways to start a story—either a stranger comes to town, or someone decides to leave. Whatever happens from there changes everything. Somehow, that simple prompt is both challenging and comforting. A lot of my time in literature courses at college was spent asking the probing question, “What is literature?” (We’ll get to WHY that’s an important question in a bit.) It seems like a simple enough question, but it always invokes a huge discussion that usually boils down to this: literature is art that uses words and language. It’s also described as a category of art—literature is always art but art is not always literature.

A lot of my time in literature courses at college was spent asking the probing question, “What is literature?” (We’ll get to WHY that’s an important question in a bit.) It seems like a simple enough question, but it always invokes a huge discussion that usually boils down to this: literature is art that uses words and language. It’s also described as a category of art—literature is always art but art is not always literature.

But let’s bring it back down to something resembling sanity. Why do we read? Usually, to learn something. When we read Shakespeare, we want to learn about the characters he’s created and the philosophy he’s trying to sell. When we read a letter or e-mail, it’s to keep up correspondence and to understand their goal or message in sending their note. When we read a magic 8 ball, we want a prediction, whether we believe it or not.

But let’s bring it back down to something resembling sanity. Why do we read? Usually, to learn something. When we read Shakespeare, we want to learn about the characters he’s created and the philosophy he’s trying to sell. When we read a letter or e-mail, it’s to keep up correspondence and to understand their goal or message in sending their note. When we read a magic 8 ball, we want a prediction, whether we believe it or not.

Recent Comments