Hello again, class.

Hello again, class.

I’m nearing the end of this blog, with only a handful of books left from the list to finish. I’ve been thinking about why certain books were chosen, and about the list overall—how the list itself affects the way someone reads the books on it. Like when I read Moby-Dick at the same time as One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Men Without Women—my thoughts about themes like insanity and masculinity felt more well-rounded.

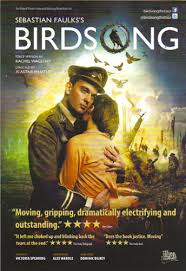

There’s something to be said for my approach . . . I imagine most people who attempt something like reading all 50 of these books do so more casually. They might add the books to some catch-all reading list and get around to it when they can, maybe jump into Ulysses as a book club or a personal reading challenge . . . and in a bookstore one day, they happen upon one of the obscure ones, like Birdsong or The Quiet American, and they buy it, only to get around to it months or even years later, remembering why they bought it in the first place. Not me—I made this list and this blog my personal mission. With any luck, I’ll have finished all 50 books in under three years, with a blog to show for it.

In reading all 50 of these books in as short a time as I could manage, I tightened the experience. It cost me in some places—reading Anna Karenina on a budgeted schedule made it hard to appreciate it in the small moments, and flying through Hamlet, even in reading it a third time, dangerously hindered my understanding of Shakespeare. But even so, I gained something as well: a greater understanding of the list itself. Most people would have read one of the books every so often, but I’ve read the list in one swift motion.

And as you, dear students, potentially read the list in its totality like I did (or like I’m doing), you might find the similarities I found. Thematic callbacks, cultural foreshadowing, opposing arguments, storytelling trends . . . every book on the list has these qualities in common. And no matter what book you pick up from the list of 50 Books to Read Before You Die, you’ll likely see these qualities pop up yourself.

The Theme of Humanity

That’s right—you’ll notice that every author on this list is a human.

Humanity as a theme is broader than people tend to give it credit for—it covers everything. All stories are human stories, and any story that claims otherwise is fiction or even fantasy told from human perspective. As a species we have defined ourselves and are constantly redefining ourselves with every story ever told, and the 50-books list reflects that.

There are fantasy stories like The Lord of the Rings or The Wind in the Willows, involving nonhuman characters doing very human things. Romantic stories like Pride and Prejudice or Wuthering Heights tell stories of romantic love . . . passionate, practical, destructive, all-consuming, redeeming love, defining one of the most human experiences we know. War stories like Birdsong or The War of the Worlds (as well as a true account of wartime, The Diary of Anne Frank), portray some of the darkest moments human history has to offer—inhumanity at its strongest. Stories relying heavily on religion like Life of Pi or The Divine Comedy tell stories about God in human contexts, and humanity’s contrast to God is so stark and vast that it could be the overarching theme of the Bible itself.

It makes sense that every work on the list has something to say, even if unintentionally, about the great human story we’re all a part of. The 50-Books list is a best-of compilation of Walt Whitman’s line of poetry—from “O Me! O Life!”, Whitman says “the powerful play goes on, and you may contribute a verse.” The list is 50 different contributions to the powerful play of life from the greatest writers of all time.

A Western Perspective

Not all of the similarities are good—and this one happens to point out some intrinsic bias on the list. There are some exceptions, but 4 times out of 5, if you pick up a book from this list you’ll be reading stories by English-speaking, first world authors.

For instance, there seem to be no Asian authors on this list, despite there being several great Asian authors like Lu Xun or Asian-American authors like Amy Tan who could have been featured. This is made worse by the fact that Caucasian writer Arthur Golden makes an appearance on the list for telling a Japanese story, Memoirs of a Geisha. It’s a great story, which unfortunately is still a Western story and a weak form of representation for a huge percentage of the world population.

Another point of contention is the Bible being featured on the list—it is the only religious text featured. The Bible itself is not a Western text; its origins are Hebrew and Middle Eastern, and it is a remarkable reflection of oral tradition and culture from a definitely not-Western history. But the Bible, like Christianity, has first-world connotations; Western cultures have a history of forcing Christianity on others, and the Bible can be and has been used as a tool to do so.

I don’t condemn the inclusion of the Bible on the list, because it has had such a huge cultural impact on stories across the globe that it’s worth reading for that reason alone. But what if another religious text was featured to balance things out? Including the Quran on the list, as an example, would have shed light on Islamic beliefs and reflected the culture of a different people—a small step in undoing social biases and bridging cultural divides, a step that this list does not take.

This doesn’t mean “don’t read from this list, it’s biased and overrated”—if that’s what I meant I would have stopped this blog a long time ago. It just means “take this list with a grain of salt.” Like all things, this list has its flaws, and it should not be treated as a sacred end-all-be-all to your personal library.

Modern Literature

I have a theory here—one that I already brought up on my post about Modernism and Postmodernism, so I won’t go into too much detail. Basically, I think that modern literature is the focal point (or maybe tipping point?) that all other literature revolves around. The modern era is the first half of the 20th Century, defined by world wars, technology, psychology, shifting morality, financial crisis, and all the art that resulted from it. I think modern literature is that which lends focus to the chaos of our world, specifically the chaos of the 20th Century, and all literature before that time is a part of the long journey building up to it.

Every book on the list (arguably) falls into this category. Older stories like Gulliver’s Travels and Don Quixote foreshadow the changing literary landscape, while novels like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Moby-Dick are prefaces to 20th Century literature. Novels from the actual time period like Ulysses, The Great Gatsby, and Men Without Women each deal with the chaos head-on—grapple with it, challenge it, fear it, and attempt to make art out of it. Novels after that period are postmodern reactions to the chaos, like To Kill a Mockingbird and The Catcher in the Rye, and more contemporary novels like Life of Pi or The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time are more like celebrations of the chaos that make the world and the people in it more interesting.

The list is a series of historical milestones, looking forward and backward to find truth in the chaos, or to at least accept the chaos as the truth. Questions posed by stories of the past are answered by stories of the present (though they answer with more questions). Each of these stories questions convention and force us to think in a modern way, and that change of perspective is everything in a good story.

How to Tell a Story

Every story on the list has a meta-storytelling approach. Or, put a different way, every story on the list is aware of itself as a story, and is all the better for it.

Most stories stop at telling a story, plain and simple. There’s nothing wrong with that; stories make the world go ’round, just as they are. But the best ones seem to reflect on themselves, challenge themselves to be better (almost like people—the best stories are the ones that are almost alive, and they can comfort, frighten, challenge, and improve us like other people can).

This usually pops up in small ways, like when a story is told in a different form. The Color Purple is an epistolary novel, which means it’s told entirely in letters—a simple method that upends the entire dynamic of the story. All eighteen chapters of Ulysses are each in a different form—a play, a series of newspaper articles, a romance novel, a catechism, and so on. Even the Bible is told in several forms—law books, poetry, parables, letters, and gospels, all with different authors, audiences, and intentions. To play with the form of a story is to find out how to tell a story in a better way.

More often than not, a book from the list will include stories within stories as a reflection on their own storytelling. Don Quixote and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn are a series of overlapping episodes and several mini-stories, told in the context of the overall story. The Canterbury Tales is a set of stories within stories within stories, all within one big story. Hamlet features its famous play-within-a-play, a common and effective Shakespeare move. Moby-Dick is filled with textbook-like interludes, almost anti-stories, with enough aesthetic merit to not feel out of place.

A lot of the authors on the list write stories about authors and storytellers, who tell stories of their own and reflect the authors’ personal narratives. Stories like The Divine Comedy and Money: A Suicide Note feature the authors themselves (Dante Alighieri and Martin Amis, respectively) as major characters. Gulliver’s Travels and The Way We Live Now feature fictional authors that the real author can use to criticize or shed light on other real life authors. Life of Pi and Memoirs of a Geisha are both disguised as works based on a true story, which gives their fictional main characters a kind of authoritative power and reorients the kind of story they are telling.

In every case, it’s about story. These are all books written for the purpose of advancing what a story can do, and what a story can be. These are all books written by people who not only know how to tell a story, but who are dedicated to telling lasting stories, and that’s why they each made the list in the first place.

I expect the remaining books on the list to have these same qualities—and I expect a lot of the great books I’ll read down the road will be similar. I know I won’t enjoy every book previously vetted by a master list like this (as we’ve seen with Money, A Bend in the River, Huckleberry Finn, etc.); but even for the books I don’t enjoy, I’ve developed a few tricks up my sleeve to see if a story is objectively good. Being able to tell the difference between a story you don’t like and a story that’s bad is a pretty useful skill.

I’m finishing up Rebecca—I’ll leave the discussion for next time. Until then,

Prof. Jeffrey

Hello again, class.

Hello again, class. But the least I can do is tell you who these unlikable characters are, and a bit about what they do that’s so unlikable. The narrator is a man named John Self, a conceited, sadistic, out-of-control addict attempting to adapt his story into a movie. He is surrounded by celebrities that are as self-absorbed as he is, as money-addicted and as morally bankrupt too. He spends his days in constant cycles of prostitutes, alcohol, smoking, and mindless purchases, and all the while he experiences a ceaseless and vulgar inner monologue that is as carefully crafted as it is offensive.

But the least I can do is tell you who these unlikable characters are, and a bit about what they do that’s so unlikable. The narrator is a man named John Self, a conceited, sadistic, out-of-control addict attempting to adapt his story into a movie. He is surrounded by celebrities that are as self-absorbed as he is, as money-addicted and as morally bankrupt too. He spends his days in constant cycles of prostitutes, alcohol, smoking, and mindless purchases, and all the while he experiences a ceaseless and vulgar inner monologue that is as carefully crafted as it is offensive.

Hello again, class.

Hello again, class.

Recent Comments