Hello again, class.

The Wind in the Willows is one of the most pleasant stories I’ve read in a long time. It’s short and entertaining, full of talking animals on crazy adventures, and never shallow enough to lose suspension of disbelief. More importantly, it’s a children’s story—easily what a parent would read to their children every night, which means unlike most novels on the 50-books list, this actually is something everyone should (and could) read.

The Wind in the Willows is one of the most pleasant stories I’ve read in a long time. It’s short and entertaining, full of talking animals on crazy adventures, and never shallow enough to lose suspension of disbelief. More importantly, it’s a children’s story—easily what a parent would read to their children every night, which means unlike most novels on the 50-books list, this actually is something everyone should (and could) read.

The story follows four animal characters, who each live on or around a great river: the Mole, the Water Rat, the Toad, and the Badger. Their stories intersect mildly, as the Mole adventurously abandons his home or the Toad tries desperately to return to his own, and the characters gather together at the end to wrap up the plot. It’s funny and sweet.

Author Kenneth Grahame

I don’t think the story and characters would be all that special, though, if it wasn’t for Kenneth Grahame’s writing. He adapted the bedtime stories he would tell his son into this novel, and because of that, he made it meaningful. Grahame balanced the animal-instinct for adventure with the desire for the comforts of home; he harnessed the distinctions between creatures and embraced those differences; and he portrayed the simple elements of nature with the same depth and complexity as the world of humanity can be perceived—at least by a child. His care for this story made it beautiful, and that’s why it makes the list.

Everything seems to have a dream-like quality as well, and that’s no mistake—the word “dream” is used obnoxiously often. Apart from a few main story arcs, most of the chapters feel like individual short stories, jumping between random plot points like a dream would. The talking animals, the exciting adventures, the beautifully comforting language . . . The Wind in the Willows is a childhood dream brought to life.

I do still question it’s inclusion on the list. The excellent writing and the portrayal of a child’s fantasy dreamworld is already on the list—Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Lewis Carroll’s classic is also much more popular and more fantasy-heavy than The Wind in the Willows, so why include Grahame’s novel at all? If we needed another children’s fantasy, we could have also included The Hobbit or Peter Pan . . . why The Wind in the Willows?

I do still question it’s inclusion on the list. The excellent writing and the portrayal of a child’s fantasy dreamworld is already on the list—Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Lewis Carroll’s classic is also much more popular and more fantasy-heavy than The Wind in the Willows, so why include Grahame’s novel at all? If we needed another children’s fantasy, we could have also included The Hobbit or Peter Pan . . . why The Wind in the Willows?

I don’t have much of an answer. It’s not that The Wind in the Willows is bad, but there are plenty of books missing from this list. Any one of them could have replaced this one. In any case, this would only be a concern if we were ranking the books on this list, and since that’s not what the list is about, I encourage you all to give this story a go.

I’m reading Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird next—for my book #25! Halfway there! And there’s no better book to wrap up the first half of my blog with.

Until next time!

Prof. Jeffrey

Good morning, class.

Good morning, class.

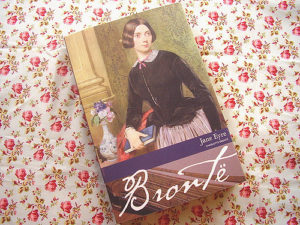

But, Gothic influences aside, what makes this story great is Jane herself. She is an excellent heroine, knowing and understanding who she is and what she deserves. She faces the consequences of her actions, refuses to let her emotions cloud her judgement, and defends her body, spirit, and worth in the face of anyone who hurts her. Even when it costs her everything, she does what any person is supposed to do—she respects herself.

But, Gothic influences aside, what makes this story great is Jane herself. She is an excellent heroine, knowing and understanding who she is and what she deserves. She faces the consequences of her actions, refuses to let her emotions cloud her judgement, and defends her body, spirit, and worth in the face of anyone who hurts her. Even when it costs her everything, she does what any person is supposed to do—she respects herself. Good morning, class.

Good morning, class.

These Odyssey references, where the name Ulysses comes from, give the novel it’s epic-ness. The length of this one day is impressive, so filled with detail that it overflows at the seams, and it still doesn’t capture every single moment of the day. The ancient has been updated to match advances in technology and societal evolution, but it still meets the same archetypes it’s known for.

These Odyssey references, where the name Ulysses comes from, give the novel it’s epic-ness. The length of this one day is impressive, so filled with detail that it overflows at the seams, and it still doesn’t capture every single moment of the day. The ancient has been updated to match advances in technology and societal evolution, but it still meets the same archetypes it’s known for.

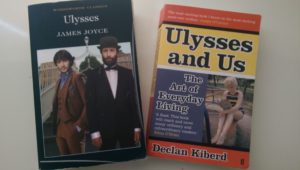

If you are going to try it, and you don’t have a literary professional standing nearby at all times, you might try reading a guidebook along with it—I recommend Ulysses and Us: The Art of Everyday Living by Declan Kiberd. It’s pretty focused on understanding the intentions behind the novel, and it helped me find the love within Ulysses. I also recommend any and all online resources—a summary won’t replace the novel, but it will help you understand what on earth is happening.

If you are going to try it, and you don’t have a literary professional standing nearby at all times, you might try reading a guidebook along with it—I recommend Ulysses and Us: The Art of Everyday Living by Declan Kiberd. It’s pretty focused on understanding the intentions behind the novel, and it helped me find the love within Ulysses. I also recommend any and all online resources—a summary won’t replace the novel, but it will help you understand what on earth is happening.

Welcome back, class.

Welcome back, class.

Don’t get me wrong—The War of the Worlds is a little dated. It’s well over a hundred years old, and sounds too much like Charles Dickens describing aliens and battle, which is jarring. Parts of the novel stumble over themselves, like when the narrator tells the story of what happened to his brother. Any modern writer wouldn’t bother explaining why two people are telling the story, but that’s too complicated for H. G. Wells’ audience—Wells’ is very careful in making his narrator explain the leap in the story.

Don’t get me wrong—The War of the Worlds is a little dated. It’s well over a hundred years old, and sounds too much like Charles Dickens describing aliens and battle, which is jarring. Parts of the novel stumble over themselves, like when the narrator tells the story of what happened to his brother. Any modern writer wouldn’t bother explaining why two people are telling the story, but that’s too complicated for H. G. Wells’ audience—Wells’ is very careful in making his narrator explain the leap in the story.

Another book finished! Welcome back, class.

Another book finished! Welcome back, class.

Recent Comments