Good morning, class.

Good morning, class.

Money: A Suicide Note and The Way We Live Now are a lot alike. Both are about greed and corruption, individually and globally. Both focus on terrible people—those who have decided on a certain lifestyle that hurts themselves and others. Both criticize the world and the poor choices people make to hold on to money or to get it by any means.

But I can’t stress this enough—I hated Money: A Suicide Note. For all it did to successfully criticize the corrupt and greedy world of the late 20th century, I couldn’t enjoy it and I couldn’t wait to be done with it. That wasn’t the case with The Way We Live Now, which wasn’t my favorite book of all time, but it was definitely more enjoyable. The Way We Live Now did for the 19th century what Martin Amis’ Money did for the 20th—portrayed a society that was as successful and wealthy as it was deplorable, with all the humor, darkness, and drama that comes with the territory.

Unlike with Money, which told everything from one biased perspective, The Way We Live Now is about the lives of a full cast of characters and shifts focus between different intersecting plots. A few main threads keep everything together and keep things moving, such as the love-life drama of Paul Montague (blatant Romeo and Juliet reference), the upcoming election for a seat in British Parliament, and the repeatedly disastrous behaviors of Sir Felix Carbury.

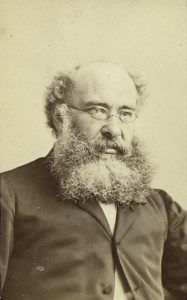

Author Anthony Trollope

Sir Felix is a spoiled son of reasonable wealth—except that he spends all his time and money gambling. His mother, too afraid of driving him away, enables him by giving him money she doesn’t have, despite what it does to her unmarried daughter, who is far less spoiled and yet far less appreciated. But Sir Felix’s spendthrift ways are nothing compared to his commitments to two different women, both of whom he cares very little for, except that they might be able to provide him with more wealth if he plays his cards right. He is the story’s source of carelessness and insincerity—the purest example of insatiable greed and the path it can lead one to.

But honestly, Sir Felix is redeemable, unlike the novel’s true villain—Augustus Melmotte, a man new to the area running for a seat in Parliament, and doing anything he can to get it. He is a typical political evil—a careful liar, a corporate-level thief, a two-faced celebrity, and a cultural phase that brings out the worst in people on a worldly scale. He steals and attempts to cover it up, abuses people close to him that would traditionally be loved ones, and refuses to accept anything that doesn’t go his way. Melmotte is a smiling, charming criminal, and is everything Sir Felix is but worse. Sir Felix is always just out of reach of being his better self, but Melmotte is nowhere near being redeemable.

Paul Montague’s story is the novel’s redemptive quality. His story is about his attempts to remain a good gentleman in the midst of his chaotic love-life—he no longer loves a woman he is intended for, and he loves someone that his closest friend hopes to marry. He makes some serious missteps, but his intentions are never unclear—he means to be a good person no matter what. He juggles his relationships to find the perfect balance, so that he can maintain his friendship, sincerely end his old engagement, and begin anew with the woman he cares for.

An illustration from The Way We Live Now, featuring Winifred Hurtle and Paul Montague

Then, the threads intersect—Montague’s love is Henrietta Carbury, Sir Felix’s sister; Sir Felix is in a threadbare relationship with Marie Melmotte, Augustus’ daughter, and Augustus disapproves of the relationship; Sir Felix is in an even more threadbare relationship with a girl named Ruby, who, after being kicked out of the house for being involved with Felix, finds herself in the same establishment as the woman Paul is trying to disengage with—an American woman named Winifred Hurtle; Melmotte, Paul, and Felix, as well as several other wealthy people, are involved on the governing board of a North American railway company. Every chapter is like a roll of the dice, and no one knows what social, political, or romantic disaster might happen next—and that does make it an exciting read.

Shifting from character to character is a strength—one that author Anthony Trollope uses to his advantage. Trollope sometimes writes from Paul’s perspective and shows Felix as deplorable as he seems, but then he writes from Felix’s perspective, without changing Felix’s actions or motivations, and makes him sympathetic (or we get to hear from the perspective of his mother or sister, to make things that much more complicated). This is a bolder move than it seems, especially for the time—the novel shows its age by having an overly helpful narrator, referring to us as the reader and guiding us on this journey. There’s some of that throughout the story—a balance between the traditional and the changing future, between the conservative and the progressive. It’s a story as time-tested as Shakespeare, and as experimental as Money.

And for all that, the reason it made the list is in the title—The Way We Live Now. This is a snapshot of English culture in the later half of the 19th century, an era more modern than it used to be and not as modern as today. Trollope’s goal was to point out how greed and corruption were plaguing English society, and with this novel, he does that with as much intrigue as balance. By focusing on that theme in its entirety, The Way We Live Now tackled a wide scope of ideas and truly reflected the world at the time, and with good writing to boot, it’s no wonder it made the list.

Next up, I’m working my way through Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier—another novel that serves as a snapshot of the era, the early 20th century. More on that next time.

Until then,

Prof. Jeffrey

Recent Comments