Welcome back, class.

In some ways, Memoirs of a Geisha was an easy book. I fell right into the story and was amazed by the character who told it. Arthur Golden’s novel was enjoyable the entire time, and I understand why it was instantly successful when first published just over 20 years ago.

Calling it “easy,” though, puts a bad spin on a novel that, at times, disturbed me so terribly that I had to put it down. The protagonist, Chiyo Sakamoto, renamed Sayuri Nitta when she becomes a geisha, is sold, abused, raped, and betrayed on what seems like a regular basis. The casual way she discusses her horrible life proves just how common her hardships were; the life of a geisha is clearly not an easy one.

Sayuri and Mameha in the film adaptation, Memoirs of a Geisha (2005)

Memoirs of a Geisha is one of those un-put-down-able books, written in such a careful style that the story sticks with you after you’ve finished it. Part rags-to-riches, part love triangle, part coming-of-age . . . it fulfills as much as it can in 400 pages. The hardships of geisha training and life are too numerous to describe in full, but Golden spares no gory detail. He let’s the elderly Sayuri tell the story in her own way, and it’s fascinating.

The rest of the characters that fill up her life—both as Chiyo the girl and Sayuri the geisha—are just as fascinating. There’s the vicious geisha Hatsumomo, the kind Chairman and his friend, the proud but generous Nobu, the impressive geisha Mameha that agrees to train Chiyo, the clumsy geisha-in-training named Pumpkin who is hopelessly manipulated by all around her, the money-obsessed Mother of the Nitta okiya . . . the list goes on, each character as interesting as the last. Through one narrator’s eyes, each character is given a fantastic life of their own, which is an amazing feat in itself.

And overall, Memoirs of a Geisha a story about destiny—how we can find it, if we can make our own, and discovering the consequences of avoiding it. Expensive kimonos, zodiac motifs, sexual favors, teahouse parties, and delicate reputations . . . all details guiding Sayuri toward a destiny she has little control over. The novel as a whole handles the theme of destiny in one of the more honest ways I’ve ever seen.

Memoirs opens with a fictional translator’s note—like Life of Pi, this entirely fictional story was advertised as based on real life. I’m not sure why Golden did this, except that it made things more interesting.

But his rich realism actually faced some backlash: Golden was criticized for misrepresenting Japanese culture and geisha life. Some of the sources I’ve found detailing this misrepresentation are here and here.

It’s clear Golden did his research, but when a white American author portrays another culture, the details seem to consistently get lost in the effort. If I knew more about Japan, the time period, and what Golden got wrong, I would be more upset about it, but I was too wrapped up in a quality story. In my opinion, the best thing for others who plan to read Memoirs is to do it with a grain of salt, and to do more research into the realities that Golden couldn’t grasp, which I plan to do. All I know for sure is that misrepresentation is dangerous, and shouldn’t be taken lightly.

Sayuri, portrayed by Ziyi Zhang in the film adaptation

I hate to leave this review on such a sour note, because the book was an incredible piece of literature . . . but it’s not okay to twist another culture into an image that fits your vision. People begin to make assumptions, claim things that aren’t true, and take for granted what one man wrote in a piece of fiction, all of which can hurt people. And it’s all from a lack of consideration.

I’ve written about this in my reviews of A Bend in the River, The Quiet American, and Robinson Crusoe. Here again, with Memoirs, a work of art is so renowned for the amazing things it’s done that people neglect to point out the negatives—the racial, political, cultural misrepresentations that affect real people. Memoirs is one of the few books on the list that I still liked, despite those misrepresentations, but I know that’s because I don’t understand what Golden did wrong. So until I know more, I’m siding with the people who felt those effects and made claims against Golden’s novel—better that than to dismiss them for speaking their truth.

Up next is Dante’s The Divine Comedy. I have a lot of thoughts . . . most of them not in favor. I’ve never read it before and I absolutely should’ve had my own literary professional on call while I read it, but I’ve been arrogantly reading it straight through without help. To see the consequences, check in next time.

Prof. Jeffrey

Tis’ the season, class.

Tis’ the season, class.

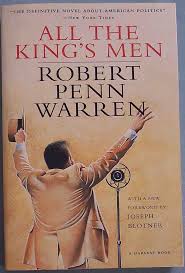

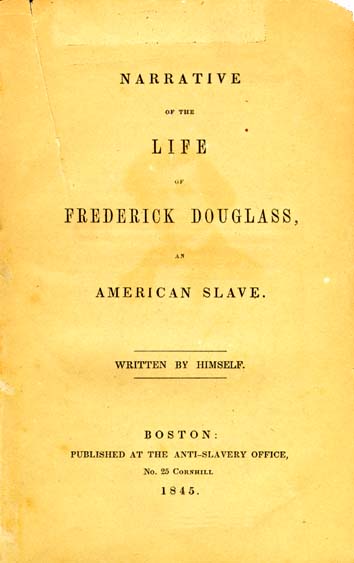

Douglass’ life also has enough historical significance that it should be read whether it’s good or not (it just so happens that it’s good writing as well). The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is an important historical milestone for the abolitionist movement of its time, which forever altered American history through the Civil War, the Civil Rights Movement, and modern race issues we still struggle with today. Like similar nonfiction works, it should be required reading for everyone—it belongs on the list because it helped change the world.

Douglass’ life also has enough historical significance that it should be read whether it’s good or not (it just so happens that it’s good writing as well). The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is an important historical milestone for the abolitionist movement of its time, which forever altered American history through the Civil War, the Civil Rights Movement, and modern race issues we still struggle with today. Like similar nonfiction works, it should be required reading for everyone—it belongs on the list because it helped change the world.

Recent Comments