Hello again, class.

At this point, I’ve picked more than 20 books that are “missing from the list”—books that I think deserve to be read as much as the “50 Books to Read Before You Die.” They all stand out for one reason or another . . . they all feature some crucial element not found on the original list. The Outsiders is hallmark young adult fiction, in a way that the other 50 books fails to deliver; The Shining is one of the best horror novels of all time, and horror in its own right is not as featured on the list as it should be; Citizen is one-of-a-kind, a cultural collage of racism in America; and there’s nothing in children’s literature quite like the works of Dr. Seuss.

Then there’s Cloud Atlas—a book that I chose to write about not because it had something crucial the list was missing . . . but because it mashes the best books on the list together. Cloud Atlas is not one book, but several—it’s a montage of genres throughout time that resonates more strongly as one piece. In a way, it’s its own library.

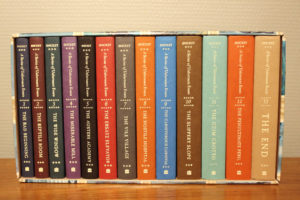

The full set of the 13 book series, A Series of Unfortunate Events, published from 1999-2006.

The same can be said of A Series of Unfortunate Events by Lemony Snicket. This 13-book series is filled to the brim with cues from the greatest books of all time, so that each new character, plot device, or unfortunate event is the makings of Lemony Snicket’s personal, quirky library. From 1984 to Moby Dick, and from the poetry of T. S. Eliot to The Little Engine That Could, Lemony Snicket filled his books with other books and made something original: a modern literary canon for kids, as well as a part-time dictionary, a how-to manual, and a kind but constant reminder that the world is a treacherous place . . . and that knowledge, dedication, and empathy are the tools one needs to fight treachery.

I’m not sure that a synopsis is needed for a series this famous, but just in case . . . this is the miserable story of the Baudelaire children, who, after a fire in their home, become the Baudelaire orphans. Violet, Klaus, and Sunny, each with their own talents and skills, are thrust into a world without the comforts of home and with only the memory of their parents, and they fall into the hands of Count Olaf, a villain who wants to steal the Baudelaire fortune. Time and again the Baudelaires escape his clutches, and time and again he catches up to them, making every chapter in their lives seem more unfortunate than the last.

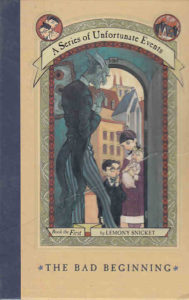

The first book, titled The Bad Beginning (1999)

And no—it’s not a happy children’s story. The narrator makes that unbelievably obvious in every single installment, writing about how dreadful the lives of these children are and how you, dear reader, would be far better off not reading this story at all. That’s part of the genius of A Series of Unfortunate Events—author Daniel Handler, who created the fictional narrator Lemony Snicket, writes in a way that makes this tragic story absurdly interesting. I’ve said it before . . . it’s almost impossible to describe, it simply has to be experienced.

There are several reasons I think A Series of Unfortunate Events should be included on the list. For one thing, the series handles concepts like grief and sadness in ways that are perfect for children and teenagers, without compromising on those concepts to make them “child-friendly.” Evil exists, and Count Olaf represents it, but that evil has been in this world long before Count Olaf appeared and it will be here long after he’s gone. Facing evil takes love, like love for a sibling, love for those we’ve lost, and love for others in this world that are suffering, who need a volunteer to help them—and not simply a blind, thoughtless love, but a courageous, unconditional love of understanding and acceptance. That kind of love can be hard to find in a world of schisms and fires, but it’s our last hope against evil, and we must cling to it.

A symbol used throughout all 13 books, revealing many secrets for the Baudelaires. It most commonly appears as the sinister tattoo on Count Olaf’s ankle.

With that as the backbone of the story, what remains is an absurd world filled with poorly named reptiles, hypnotism, a pit of hungry lions, several angry mobs, a bad acting troupe, vicious leeches, a deadly fungus, and a secret organization filled with codes, disguises, weapons, and more mysteries than can be imagined. The story is ridiculous, often funny even, and stands out accordingly.

And for all that, there’s a reason it belongs on the list that’s special—the thing that makes this series special, not just among children’s literature but among all stories. It’s the same thing that makes Cloud Atlas special—A Series of Unfortunate Events is, among other things, a complicated concoction of the greatest moments of literature, and that blended result is something entirely different than what came before. It’s even a direct reflection of the 50-books list itself, taking the old stories and making them new. A Series of Unfortunate Events is a library all on its own, and this is a story that loves how a library can be a kind of sanctuary—a place that fosters curiosity, provides access to knowledge, and can be one of the last safe places in a dangerous world.

This blogger can testify that stories and books have always been a refuge. Stories can take you places you’ve never seen, reveal truths you’ve never imagined, and comfort you when you’ve never been lonelier. Lemony Snicket understands that better than most, and he understands that stories can give you the tools you need to go out into the world after you’ve set the book down. Even if this series isn’t for everybody, I can personally testify that it’s one of the forces of good in our treacherous world.

I’m not sure if I can say the same about Catch-22, which I’m still finishing up for next time. I’ve said already that it’s sort of an anti-story—and an anti-war story to boot. It’s experimental, and that’s always a plus in my readings. I think there’s a subtle reference to Catch-22 in A Series of Unfortunate Events, but I can’t be completely sure—emotionally, the two stories aren’t that far apart from each other, so it doesn’t surprise me. The horrors of war played for laughs in a comedy of the absurd would be the perfect inspiration for the Baudelaire’s ridiculously miserable lives.

Either way . . . more on Catch-22 next time. Until then,

Prof. Jeffrey

Recent Comments