Welcome back, class.

Welcome back, class.

Peter Pan seems accidentally special—like it struck the right cord with its audience and they never let it go. It’s inventive and ageless, but it’s also simple. It’s for children, written by a man that seemed never to grow up (and I mean that only in a good way), so there’s a reason it’s so magical. Reading it as an adult, I picked up on the fact that Peter Pan wasn’t meant for me at all—it only clued me in on the fact that, being a grown-up, my innocence was already gone. The rest of its efforts were directed towards its childhood audience.

Compare Peter Pan to a good Pixar movie, for example—they are family movies, and while they are kid-oriented, they are as much for the parents as they are for the kids. The Incredibles is as much a story about the children with superpowers as it is about the two superhero parents, in a struggling marriage and trying to keep their family together. Inside Out is the story of 5 different characters—emotions—making developmental decisions on behalf of a young girl, and I promise you that’s more for the parents’ benefit than for the kids’.

But that’s not Peter Pan—just like The Outsiders by S. E. Hinton, which was written by a teenager for teenagers, Peter Pan is about children and, in its way, written by a man that might as well have been a child. That’s why it should have made the list of books everyone should read before they die.

A statue of Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, which served as inspiration for J. M. Barrie as he wrote the story.

Growing up, I knew the story of Peter Pan from its adaptations—the animated Disney film was familiar, and a few spin-off/prequel books pulled a Wicked and made Captain Hook the focus. But my favorite adaptation is the 2003 movie, staring Jeremy Sumpter as Peter Pan and Jason Isaacs as Captain Hook. By staying more faithful to J. M. Barrie’s original story, it was a darker take—to my surprise, the original novel is darker than it appears.

For one thing, Peter himself is everything a child can be when unsupervised. He is innocent, impulsive, and (to use the novel’s exact word) heartless. There’s something unnatural, even monstrous, about this boy that never grows up—we don’t really get to the point that we’re supposed to fear him, but being his friend is not something you’d want. Maybe that’s the adult in me talking . . . who’s to say?

Then there’s Wendy Darling and her two siblings, John and Michael, who escape with Peter impulsively to fly to Never Never Land, where they might get the chance to remain children forever. They meet Peter’s gang of Lost Boys (a nicer crew than the Lord of the Flies boys, but same principle); they see mermaids, fairies, Indians (yes, this is fairly racist and does not age well); and they fight pirates, specifically the maddeningly evil Captain Hook, who hates Peter with a burning passion. Adventure ensues.

Author J. M. Barrie

I’ve compared Peter Pan to The Wind in the Willows before—both are simple stories, meant specifically for children, as opposed to stories like Alice in Wonderland. Lots of children’s stories are allegory and symbolism, meant to convey deeper meanings for the people that look for them. Alice in Wonderland makes a point to criticize society through methods specifically for adults to understand, unbeknownst to the children enjoying the fantasy. While Peter Pan certainly has its moments of meaning—powerful, moving moments—they aren’t buried in literary codes. The amazing things about Peter Pan are on the surface, not between the lines.

And one of the things that makes Peter Pan so amazing is Never Land itself—it’s Disney World. It’s an imaginary theme park, complete with every fantasy creature and villain a typical child wants. Wonderland and Oz are mighty scary at times, but Never Land is a dream come true. Even the pirates and the danger they pose are fun and exciting. Never Land is imagination, and Peter Pan is fantasy come true—that’s why it should have made the list.

I’m just finishing The Way We Live Now by Anthony Trollope—it may be from the same era and even location as Peter Pan, but they are both about as far apart as The Lord of the Rings and The Lord of the Flies. So I’ll save my discussion for next time. Until then,

Prof. Jeffrey

I’ve made it clear that my favorite eras of literature are

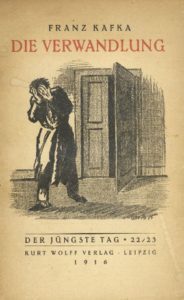

I’ve made it clear that my favorite eras of literature are  The story doesn’t waver from this approach. The Metamorphosis is the most absurd family drama ever written, about how a family deals with the weight of their dutiful Gregor’s untimely transformation. Any truly fantasy narrative would capitalize on the strangeness of the fantasy, but instead, Kafka makes his story about the regular struggles of everyday life—just with an added wrinkle. Few novels can pull this off well, so for that alone, The Metamorphosis deserves to be on the list.

The story doesn’t waver from this approach. The Metamorphosis is the most absurd family drama ever written, about how a family deals with the weight of their dutiful Gregor’s untimely transformation. Any truly fantasy narrative would capitalize on the strangeness of the fantasy, but instead, Kafka makes his story about the regular struggles of everyday life—just with an added wrinkle. Few novels can pull this off well, so for that alone, The Metamorphosis deserves to be on the list.

Welcome back, class.

Welcome back, class.

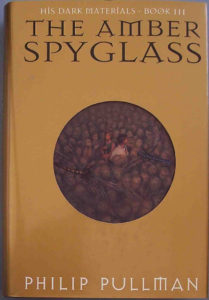

But for Pullman, it wasn’t enough to point out the corruption of religious institutions—his novels attempt to reveal corruption in the existence of God. He writes about the ongoing battle of humanity, between those who humbly submit to a greater power and those who seek wisdom and refute oppression. His novels point out the inherent immorality of a Kingdom of Heaven, like the immorality of any dictatorship in the modern age. The overarching plot of the trilogy goes so far as to use Christian theology (and mythology) to dismantle the Christian story of God—portraying God as the villain of humanity’s ongoing battle.

But for Pullman, it wasn’t enough to point out the corruption of religious institutions—his novels attempt to reveal corruption in the existence of God. He writes about the ongoing battle of humanity, between those who humbly submit to a greater power and those who seek wisdom and refute oppression. His novels point out the inherent immorality of a Kingdom of Heaven, like the immorality of any dictatorship in the modern age. The overarching plot of the trilogy goes so far as to use Christian theology (and mythology) to dismantle the Christian story of God—portraying God as the villain of humanity’s ongoing battle.

Unlike The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit is a children’s novel—the story is simpler, with the same feel as The Wind in the Willows or Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. But it doesn’t sacrifice the depth of Tolkien’s fantasy world by being kid-friendly; Middle-Earth is more extravagant and complete than Narnia, Neverland, and Oz combined. The only difference in The Hobbit is that it’s for all ages.

Unlike The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit is a children’s novel—the story is simpler, with the same feel as The Wind in the Willows or Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. But it doesn’t sacrifice the depth of Tolkien’s fantasy world by being kid-friendly; Middle-Earth is more extravagant and complete than Narnia, Neverland, and Oz combined. The only difference in The Hobbit is that it’s for all ages.

Recent Comments