Welcome back, class.

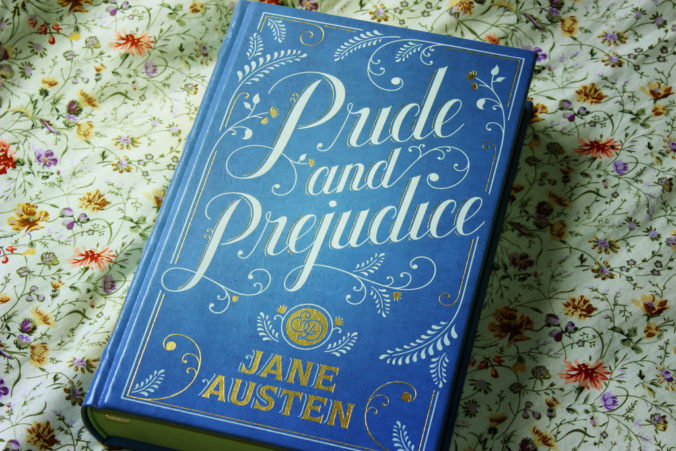

I was once gushing about my newfound favorite novel, Ulysses by James Joyce (blog post pending), to a professor who could gush just as easily over Jane Austen’s novels. I explained that Ulysses broke all the rules and changed literature like nothing ever had, and my professor didn’t hesitate; she said “Jane Austen did that already, about 100 years before Ulysses was published.”

She had a point. Since then, I may have only read one Austen novel, but it really did call every rule into question. I’ve said it before, I’ll say it again: the novels that break the rules are my favorite ones.

Elizabeth and Mr Darcy (played by Kiera Knightly and Matthew Macfadyen, respectively)

Chances are good that you know the story: an unlikely love develops between Elizabeth Bennet and Fitzwilliam Darcy. Elizabeth is a lower class girl who speaks her mind, often against others’ wishes, and is more concerned with her own happiness than anyone else’s. Mr. Darcy is a very proud, very rich man, who is so bad at conversation and social obligations that he comes off as a terrible person. Mr. Darcy’s pride and Elizabeth’s prejudice against her first impression of him are the road blocks they must overcome (hint, hint).

Beyond these personal road blocks, there are the general expectations of 19th century society that stand in their way, and Austen is ruthless in criticizing them. The famous opening lines do this best: “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” For most of the men in the novel, this is accurate; for Mr. Darcy, pinning down a wife is the furthest thing from his mind. Falling in love with Elizabeth is the only thing that changes his position.

Depiction of Jane Austen

Most of Austen’s criticisms come through Elizabeth’s mother—an incredibly foolish woman whose only desire is to see her daughters married. For instance, when her middle daughter runs away with a man, she is driven to constant bed rest and hysterics from the shame . . . until she finds out her daughter and this man will be married, and it becomes the happiest day of her life. Elizabeth narrowly dodges the bullet of becoming like her mother, but some of her sisters—uncontrollably silly, uneducated, and trapped by skewed perspectives—aren’t so lucky.

These flaws are not one character’s fault—Austen’s criticism is of a society that perpetuates those flaws. This is why Elizabeth is such an amazing character: she not only sees most of these flaws, but also acts against them. She denies the rules that mean nothing to her, and adheres to the ones that she chooses to adhere to. She isn’t perfect—her first impressions of Mr. Darcy can prove that—but she is herself, more than most literary characters and more than most people in the real world.

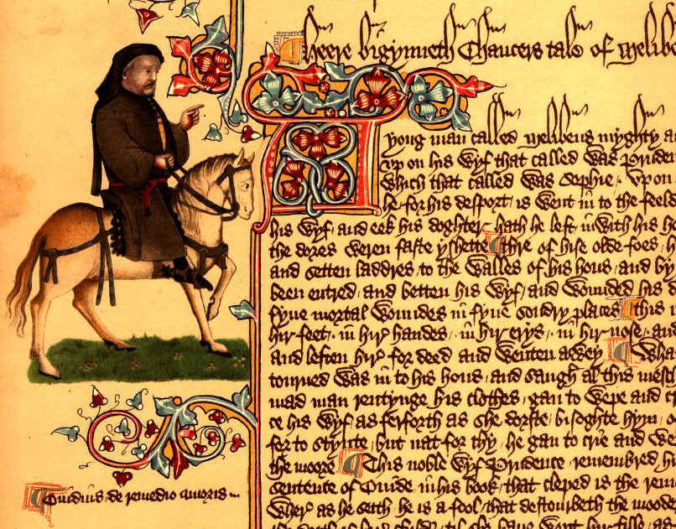

As some supportive evidence, Pride and Prejudice is based on Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, which I wrote about last week. Elizabeth strives to be herself in a world of disguises, which happens to be a major motif of Twelfth Night. And, of course, Elizabeth’s mother is the Fool from the play—except the Fool is much wiser. Plus about a thousand other connections.

I’d also like to add that for me, it took me several chapters of Pride and Prejudice before I became impressed. If you pick it up, know that it’s the kind of novel where you need to invest yourself—the drama is only DRAMATIC if you let it be. Otherwise, it’ll feel like hundreds of pages of “Good heavens!” which, personally, I can only take so much of.

Up next, I’m picking up what I think is the exact opposite kind of novel—The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, another that I’d never heard of before the 50-books list. All I know is that a dog is murdered and we’re going to solve the mystery. That’s a good enough place to start.

Until then,

Prof. Jeffrey

That being said, Pi’s ordeal is terrifying, graphic, and even hilarious at times. The tiger—named Richard Parker, in a strange origin story—is as much a character as Pi, and their journey toward communicating with each other is a roller coaster. Richard Parker can never be trusted, and though there are moments that indicate he is more than an animal, Pi is constantly reminded of Richard Parker’s natural instincts. Any moment of weakness from Pi could mean death…for both of them.

That being said, Pi’s ordeal is terrifying, graphic, and even hilarious at times. The tiger—named Richard Parker, in a strange origin story—is as much a character as Pi, and their journey toward communicating with each other is a roller coaster. Richard Parker can never be trusted, and though there are moments that indicate he is more than an animal, Pi is constantly reminded of Richard Parker’s natural instincts. Any moment of weakness from Pi could mean death…for both of them.

Good morning class.

Good morning class.

Recent Comments