Hello again, class.

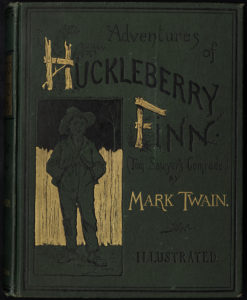

I have mixed feelings about The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. I’ve read it a lot, and I’ve hated it, loved it, misunderstood it, and been indifferent to it. I’ve thought of Mark Twain as a genius, and sometimes I’ve thought of him as a glorified hillbilly whose works we read for unknowable reasons. More often than not, I land on the idea of appreciating Huckleberry Finn from a distance, never quite sure what to make of it while knowing that it’s worth reading—that’s the mood for today.

If only reviewing books was a simple task.

The book opens with a notice, explaining that anyone attempting to find motive, moral, or plot in this story will be subsequently prosecuted, banished, or shot. From the opening page, this book flaunts narrative, which is a hole-in-one from where I’m standing. The story that follows is a series of funny and dramatic events with a few well-developed and desperate characters and a barrage of side-character kooks to keep things light and interesting. It’s meant to be a delightful adventure story, through and through.

The book opens with a notice, explaining that anyone attempting to find motive, moral, or plot in this story will be subsequently prosecuted, banished, or shot. From the opening page, this book flaunts narrative, which is a hole-in-one from where I’m standing. The story that follows is a series of funny and dramatic events with a few well-developed and desperate characters and a barrage of side-character kooks to keep things light and interesting. It’s meant to be a delightful adventure story, through and through.

Or is it? One of my issues reading Huckleberry Finn is also one of the things that has kept it popular in the century-and-then-some that came after—the story itself is more than it claims to be. No one narrative-identity sticks—it can never be limited to “adventure story.” The series of adventures do have some underlying meaning, even if the notice at the beginning tells the reader not to look for it.

But I’ve gotten ahead of myself—the only way this anti-narrative story even remotely works is because it has good characters. Huck is a boy in the American South, and he comes from an impoverished world with an abusive father. He views himself as a wrongdoer, or as trash, so he oscillates between wanting to do what’s right and giving up to do wrong. This puts him directly on the path of running away with an adult slave, Jim, whose relationship with Huck is tumultuous, subtle, carefree, and one of the strongest examples of friendship literature has to offer.

But I’ve gotten ahead of myself—the only way this anti-narrative story even remotely works is because it has good characters. Huck is a boy in the American South, and he comes from an impoverished world with an abusive father. He views himself as a wrongdoer, or as trash, so he oscillates between wanting to do what’s right and giving up to do wrong. This puts him directly on the path of running away with an adult slave, Jim, whose relationship with Huck is tumultuous, subtle, carefree, and one of the strongest examples of friendship literature has to offer.

Twain’s portrayal of Jim is remarkable—we see all through Huck’s eyes, and Jim’s actions show him to be far more than Huck can imagine of a slave. Just like the story, Jim is more than he seems, and for all the stereotypes he seems to embody of a submissive and hard-working slave, he subtly flaunts those stereotypes in the story’s stiller, smaller moments. Twain wrote him as both a caricature and an honest deconstruction of slave characters—and Jim is one of the reasons Huckleberry Finn is still read today.

Author Samuel Clemens, a.k.a Mark Twain

Twain’s real writing strength is his humor. Throughout Huckleberry Finn, there are disguises, pranks, puns, hilarious literary references, bumbling idiots and smart people fooled beyond recognition. Two characters known as the king and the duke swindle money from people for a living, and comedy ensues. Huck’s profound misunderstanding of most situations leads to hilarious chaos. One extended joke about two feuding families references Romeo and Juliet constantly, and Twain’s version isn’t half as tragic (that’s what he’d have you believe, in any case). Huck even dresses up like a girl to get information from someone. It’s non-stop, and Twain is a master of hilarity.

I can’t deny, even though I clearly think it’s a good novel, that I can’t stand Huckleberry Finn. Part of it is the overuse of the n-word, but that’s a weak reason—I love To Kill a Mockingbird for the same “fault.” Part of it is that this boy’s adventures are so unlike my life that I have no frame of reference; there’s almost no way his running away with a slave matches any moment in my own narrative. But that’s a weak reason, too—I could say the same about so many books I’ve praised before, including Pride and Prejudice, Brave New World, The Color Purple, As I Lay Dying, and To the Lighthouse.

It probably boils down to taste, and that’s the best answer you’ll get out of me. I’ll praise the genius of Huckleberry Finn while keeping my distance; there are several novels I’ll reread for pleasure, and this isn’t one of them. But I wholeheartedly agree that it’s one of the 50 books everyone should read before they die.

Next up, I’m finishing Moby-Dick—another story that is so unlike my own life that I have little to no frame of reference. But unlike with Huckleberry Finn, I very much enjoyed Moby-Dick even in spite of its flaws . . . but more on that next time.

Until then,

Prof. Jeffrey

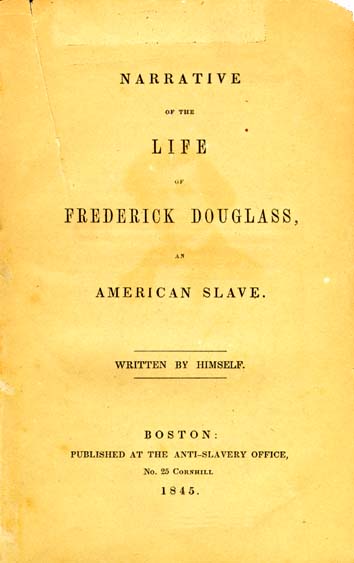

Douglass’ life also has enough historical significance that it should be read whether it’s good or not (it just so happens that it’s good writing as well). The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is an important historical milestone for the abolitionist movement of its time, which forever altered American history through the Civil War, the Civil Rights Movement, and modern race issues we still struggle with today. Like similar nonfiction works, it should be required reading for everyone—it belongs on the list because it helped change the world.

Douglass’ life also has enough historical significance that it should be read whether it’s good or not (it just so happens that it’s good writing as well). The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is an important historical milestone for the abolitionist movement of its time, which forever altered American history through the Civil War, the Civil Rights Movement, and modern race issues we still struggle with today. Like similar nonfiction works, it should be required reading for everyone—it belongs on the list because it helped change the world.

Recent Comments