Happy Holidays, class! Let’s talk about nonfiction.

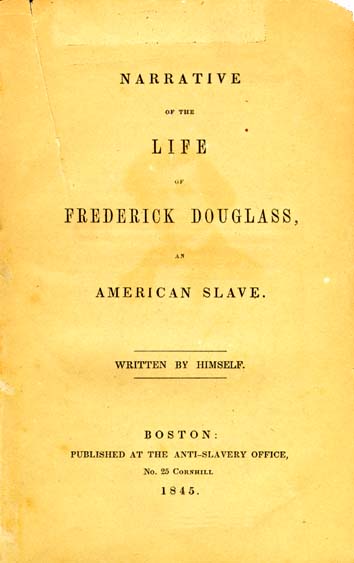

The full title of the work is Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself.

While the Bible depicts some historical events, the only nonfiction work on the entire 50-books list is The Diary of Anne Frank (which I will write more about in a future post). And though I think the nonfiction novel In Cold Blood by Truman Capote is missing from the list, too, I also believe so about the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass—for entirely different reasons. In Cold Blood is an unnerving look at humanity’s desire for witnessing a brutal and real crime. In some ways, Douglass’ Narrative is similar—Douglass shows the criminality of slavery that scarred his own life and American society as a whole. But it’s a redeeming tale, too, revealing the outcomes of perseverance against a system of oppression . . . one that Douglass defies with his very existence.

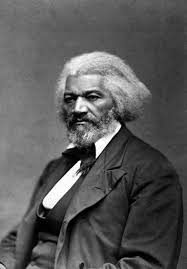

Douglass writes of his life growing up as a slave, the people who influenced him, and the realizations he came to in his hardships. He’s a traditional storyteller, which he was likely conscious of in order to attract a traditional audience—the kind of audience who needed to read his story, and to understand his humanity. His experiences can affect hearts and minds by their ever having been allowed to happen.

And while each of his experiences are both meaningful and inhumane, one stands out to me every time. The wife of his slaveowner begins to teach Douglass to read, until her husband stops her and tells her it’s illegal and will “spoil” the slave for life . . . meaning that reading tends to empower a slave beyond a slaveowner’s control. This is not only all the evidence Douglass’ story needs to prove his own humanity—that his intellect, as a human quality, cannot be denied—but this is also the passage that proves that reading can set a person free.

It makes me think of all those blissfully stupid inspirational posters in public schools about how knowledge is power and how reading can take you to the stars. It makes me think of the stress parents and teachers put on the importance of reading and learning. Our society’s idea that reading is everything came from stories like Douglass’ Narrative—where the kindness of a fellow soul and the strength of a human mind can conquer slavery, and where reading can change lives.

Douglass’ life also has enough historical significance that it should be read whether it’s good or not (it just so happens that it’s good writing as well). The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is an important historical milestone for the abolitionist movement of its time, which forever altered American history through the Civil War, the Civil Rights Movement, and modern race issues we still struggle with today. Like similar nonfiction works, it should be required reading for everyone—it belongs on the list because it helped change the world.

Douglass’ life also has enough historical significance that it should be read whether it’s good or not (it just so happens that it’s good writing as well). The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is an important historical milestone for the abolitionist movement of its time, which forever altered American history through the Civil War, the Civil Rights Movement, and modern race issues we still struggle with today. Like similar nonfiction works, it should be required reading for everyone—it belongs on the list because it helped change the world.

As I continue to read Memoirs of a Geisha by Arthur Golden, the fictional account of a geisha’s life in the first half of the 20th Century, I’m noticing similarities between it and Douglass’ Narrative, if only in the way the story is told. The attempt to reflect on one’s own life and tell as rounded a story as possible is something no one can completely achieve. Douglass’ story is, more often than not, about slavery, and not about himself. The picture he paints for us reveals the experiences that affected him more than it reveals his character. To describe yourself, using your own point of view, is one of those impossible things human beings always try and fail to do—which actually makes Douglass’ Narrative more meaningful and Golden’s Memoirs of a Geisha more enjoyable.

More on that next class!

Prof. Jeffrey

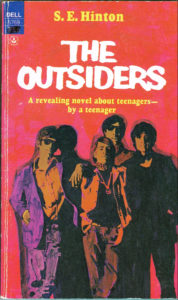

So this book—of teenagers, by a teenager, and for teenagers—was one of the first of its kind, and remains the embodiment of young adult literature even today. It clearly should be on the list.

So this book—of teenagers, by a teenager, and for teenagers—was one of the first of its kind, and remains the embodiment of young adult literature even today. It clearly should be on the list.

Virginia Woolf is one of those hallmark authors who stand out by reputation alone, regardless of sex as a qualifier, while still being one of the clearer representatives of feminism known in literature. The fact that she has no novel on the 50-books list highlights the fact that so many other women are left off of it, too.

Virginia Woolf is one of those hallmark authors who stand out by reputation alone, regardless of sex as a qualifier, while still being one of the clearer representatives of feminism known in literature. The fact that she has no novel on the 50-books list highlights the fact that so many other women are left off of it, too.

Something I tend to forget about modernism is its obsession with time. Novelists from this period liked to portray the unreliability of time by reorganizing chronological order, speeding up and slowing down the story, and confusing a single moment with an eternity. Virginia Woolf fit right in with these modernists—entire chapters in parts 1 and 3 of To the Lighthouse take place in seconds, while part 2 speeds through ten years in no time at all. The action of parts 1 and 3 is also mostly internal, letting stream-of-consciousness explain characters and their motivations—something modernism all but invented.

Something I tend to forget about modernism is its obsession with time. Novelists from this period liked to portray the unreliability of time by reorganizing chronological order, speeding up and slowing down the story, and confusing a single moment with an eternity. Virginia Woolf fit right in with these modernists—entire chapters in parts 1 and 3 of To the Lighthouse take place in seconds, while part 2 speeds through ten years in no time at all. The action of parts 1 and 3 is also mostly internal, letting stream-of-consciousness explain characters and their motivations—something modernism all but invented.

Thankfully, the comparisons between Brave New World and The Giver end there. For all its similarities, The Giver is actually something quite different, and that’s why I think it should make the list of books to read before you die.

Thankfully, the comparisons between Brave New World and The Giver end there. For all its similarities, The Giver is actually something quite different, and that’s why I think it should make the list of books to read before you die.

Capote and Lee went researching after the murders were committed to tell the story: Herbert and Bonnie Clutter, and their two youngest children Nancy and Kenyon, were killed on November 15, 1959 by Dick Hickock and Perry Smith. The novel follows the murderers, the victims, and the rest of Holcomb leading up to and following the crime.

Capote and Lee went researching after the murders were committed to tell the story: Herbert and Bonnie Clutter, and their two youngest children Nancy and Kenyon, were killed on November 15, 1959 by Dick Hickock and Perry Smith. The novel follows the murderers, the victims, and the rest of Holcomb leading up to and following the crime.

Unlike The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit is a children’s novel—the story is simpler, with the same feel as The Wind in the Willows or Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. But it doesn’t sacrifice the depth of Tolkien’s fantasy world by being kid-friendly; Middle-Earth is more extravagant and complete than Narnia, Neverland, and Oz combined. The only difference in The Hobbit is that it’s for all ages.

Unlike The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit is a children’s novel—the story is simpler, with the same feel as The Wind in the Willows or Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. But it doesn’t sacrifice the depth of Tolkien’s fantasy world by being kid-friendly; Middle-Earth is more extravagant and complete than Narnia, Neverland, and Oz combined. The only difference in The Hobbit is that it’s for all ages.

Good morning class.

Good morning class.

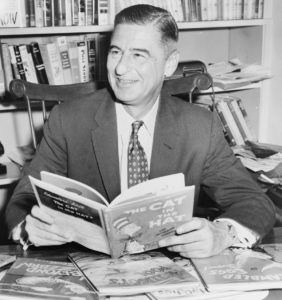

I think it’s a stroke of genius from Dr. Seuss that the Grinch hates Christmas simply for the sake of hating Christmas. He hates the noise and the feasting and the singing—there’s no explanation, just that he hates it from the bottom of his too-small heart. It makes him instantly unlikable and easy to transform by the end.

I think it’s a stroke of genius from Dr. Seuss that the Grinch hates Christmas simply for the sake of hating Christmas. He hates the noise and the feasting and the singing—there’s no explanation, just that he hates it from the bottom of his too-small heart. It makes him instantly unlikable and easy to transform by the end.

In a

In a  The Hunger Games Trilogy didn’t get the same advantage—the first installment was published in 2008, and the final installment in 2010, a year before the official list was released. If the list had been made later, I honestly believe this series would have been included. But, as always, let’s talk about why.

The Hunger Games Trilogy didn’t get the same advantage—the first installment was published in 2008, and the final installment in 2010, a year before the official list was released. If the list had been made later, I honestly believe this series would have been included. But, as always, let’s talk about why.

The story: a small, struggling family watches over the Overlook Hotel through the winter, as supernatural forces try to tear them apart. The father’s alcoholism leaves him vulnerable to the violent spirits in the hotel, and he becomes monstrously abusive. His wife tries to protect their little boy, who just happens to have the ability to communicate with the spirits around them—an ability called shining.

The story: a small, struggling family watches over the Overlook Hotel through the winter, as supernatural forces try to tear them apart. The father’s alcoholism leaves him vulnerable to the violent spirits in the hotel, and he becomes monstrously abusive. His wife tries to protect their little boy, who just happens to have the ability to communicate with the spirits around them—an ability called shining.

Recent Comments