Welcome back class.

Movies have always connected with me. My interest in writing comes from falling in love with the stories in movies—and one of the greatest things a movie can do is bring a novel to life. It’s never perfect and often falls short—it takes severe dedication, risk, and miracle work, and even then the stars need to align correctly. When it does work, though, the result is imagination made into reality.

From many books on the list of 50 Books to Read Before You Die, several filmmakers, writers, actors, composers, designers, and artists have taken a powerful story, done the heavy lifting, and made a faithful adaptation—the authors’ and readers’ dream-come-true. Some are good, some are great, and some are above and beyond my favorites.

So here they are, my favorite movie adaptations from the list of 50 Books to Read Before You Die—in order of release date (and click on the links to see what I thought of the original novels!).

Actor Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch in To Kill A Mockingbird (1962)

When a classic novel is put to screen, it’s unlikely that it competes with the original—much less becomes a classic itself. To Kill a Mockingbird does just that. The movie has stood the test of time, much like the novel, and is a powerful perspective on race, racism, Southern culture, morality, and childhood.

There are several things that make the movie special, but the cherry on top is always going to be actor Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch. I’ve never seen him in anything else, but this movie alone proves to me he was one of the greatest actors of his time, and his compassionate, reserved, and compelling portrayal of such a wise father and dedicated lawyer stands out as one of the movie’s strongest attributes. He is one of my favorite father figures in both literature and film, and there’s only a handful of characters I can say that about.

Actress Whoopi Goldberg, who portrayed Celie in The Color Purple (1985)

This was one of the first movies from Steven Spielberg that proved he could do it all—not just sci-fi adventures or summer blockbusters, but serious dramas that come from places of pain and joy and soul. After movies like E.T. and the Indiana Jones franchise, he helped bring to life the story a black woman separated from her sister, who subsequently discovers her sexuality and challenges the lot life has given her. The movie was beautiful and made me cry as much as the book did.

I grew up seeing Whoopi Goldberg as the comedic counterpart of any movie she was in; but seeing her in The Color Purple as Celie changed my view of her. She portrayed a woman who knew only hardship and grief, who had had her life stripped away from her, and who was able to find love and mercy in the everyday terror of her life. It’s not an easy movie to watch (neither is the book easy to read); but it’s the kind of movie that tells a worthwhile story, and in an age of action-packed blockbusters, The Color Purple is a precious gem.

Kenneth Branagh, director of and lead star in Hamlet (1996)

There are lots of Hamlet‘s out there. There are at least five Hamlet movies I know of acclaimed enough to be worth mentioning. But Kenneth Branagh’s version is my favorite for many reasons. For one thing, it’s one of the only Hamlet adaptations that put the entire drama to screen—and it paid the price, clocking in at a four-hour running time and milking the original text for all it’s worth.

Hamlet (1996) didn’t limit itself to accuracy though—it also happens to take place in the 19th century, far beyond Shakespeare’s time, and the dynamic setting and garish colors make a point of proving that true Shakespearean genius has never been limited to the words on the page. Most of Kenneth Branagh’s adaptations of Shakespeare have been masterpieces, and this one is arguably the best modern Shakespeare movie there is.

Movie poster for Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (2001)

I’m not picking a favorite Harry Potter movie (nor am I picking a least favorite, and believe me, I have a couple in mind). No, I take this childhood-altering series altogether, magic and warts and all—this movie franchise defined a huge portion of my life, and the ten-year journey I took with the characters in these films (along with the child actors that my generation and I grew up with) is half of the reason these are some of my favorite movies ever.

I have to admit something I don’t like to admit. I read all of the Harry Potter books before seeing the movies . . . all except the first one. For as much as I love reading, I can drag my feet around a new book unless I have a good reason to dive into it—something interesting to look for, or if it’s somehow pertinent to my life. This was the case for the first Harry Potter book, which I ignored until being swept up by the magic of the movie adaptation of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, and that started a reading journey that has affected me to this day. Most of what I’ve read in my lifetime stemmed from a love of the Harry Potter series, and all of my love for the Harry Potter series stemmed from my love for that first movie—and I’m overwhelmingly grateful for it.

From left to right: Actors Dominic Monaghan, Elijah Wood, Billy Boyd, and Sean Astin portraying Meriadoc Brandybuck, Frodo Baggins, Peregrin Took, and Samwise Gamgee in The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001).

The Lord of the Rings movies are some of the best movies ever made. Not just the best book-to-film adaptations, not just the best fantasy movies . . . they’re some of the best, period. There are movies where the amazing dedication of filmmakers combines with an alignment of the stars that blesses the work from beginning to end—this is the case for all 9 hours of this fantasy trilogy.

These movies are some of my favorites for several reasons—the most important of which is that I watched them growing up, right alongside Harry Potter. The actors are perfect, notably Andy Serkis, Ian McKellen, Elijah Wood, Viggo Mortensen, Sean Astin . . . and the list could go on! The aesthetics and special effects make this trilogy stand out as one of the most beautiful stories ever put to film—these movies proudly delivered Tolkien’s masterful world on a silver screen. It’s worth noting that the music by Howard Shore is some of the best movie music ever composed. The movies do such a good job of telling the original story that they have earned a place in my heart beyond what the book was able to accomplish—there aren’t many movies that can boast the same.

Matthew Macfayden and Keira Knightley in Pride and Prejudice (2005)

This one surprised me. I didn’t expect a movie about a woman finding love in Victorian Era England to be so impressive, but it roped me in. The colors, the music, the elaborate nature of each scene . . . the emotional undercurrent of every interaction and the display of intelligence in every creative decision, all of it tied together so succinctly. I could fawn over this movie for days.

The 1990s mini-series is worth mentioning in the same breath, for its stronger sense of accuracy and its dedication to what makes the original novel so special. But there’s something about the 2005 movie that takes the spirit of the story and transforms it into film. Part of it has to do with Keira Knightley and Matthew Macfayden, the two amazing actors that brought Elizabeth Bennett and Mr. Darcy to life. There’s always something special happening when Knightley is on screen in any movie, often being her most Victorian self, and Macfayden seemingly came out of nowhere born to play the awkward, reserved, frustrating, deeply passionate Mr. Darcy. Pride and Prejudice was always simultaneously social commentary and a love story for the ages, and this movie manages to bring that much to life and more.

There are other movies out there adapted from the list that I haven’t seen, so this is a tentative line up—but like any good English major, I plan on reading the books first, so those other movies will have to wait.

I’m finishing up Moby-Dick and I’ll share my thoughts soon. More on that next time!

Prof. Jeffrey

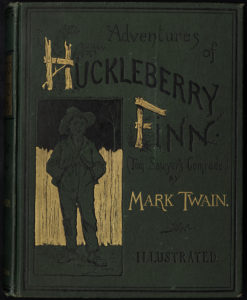

The book opens with a notice, explaining that anyone attempting to find motive, moral, or plot in this story will be subsequently prosecuted, banished, or shot. From the opening page, this book flaunts narrative, which is a hole-in-one from where I’m standing. The story that follows is a series of funny and dramatic events with a few well-developed and desperate characters and a barrage of side-character kooks to keep things light and interesting. It’s meant to be a delightful adventure story, through and through.

The book opens with a notice, explaining that anyone attempting to find motive, moral, or plot in this story will be subsequently prosecuted, banished, or shot. From the opening page, this book flaunts narrative, which is a hole-in-one from where I’m standing. The story that follows is a series of funny and dramatic events with a few well-developed and desperate characters and a barrage of side-character kooks to keep things light and interesting. It’s meant to be a delightful adventure story, through and through. But I’ve gotten ahead of myself—the only way this anti-narrative story even remotely works is because it has good characters. Huck is a boy in the American South, and he comes from an impoverished world with an abusive father. He views himself as a wrongdoer, or as trash, so he oscillates between wanting to do what’s right and giving up to do wrong. This puts him directly on the path of running away with an adult slave, Jim, whose relationship with Huck is tumultuous, subtle, carefree, and one of the strongest examples of friendship literature has to offer.

But I’ve gotten ahead of myself—the only way this anti-narrative story even remotely works is because it has good characters. Huck is a boy in the American South, and he comes from an impoverished world with an abusive father. He views himself as a wrongdoer, or as trash, so he oscillates between wanting to do what’s right and giving up to do wrong. This puts him directly on the path of running away with an adult slave, Jim, whose relationship with Huck is tumultuous, subtle, carefree, and one of the strongest examples of friendship literature has to offer.

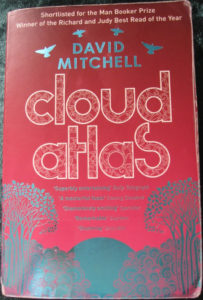

The first story is from the perspective of the attorney Adam Ewing on a Pacific ship in the 1800s, writing his experiences in his journal. The journal stops midway and picks up with an entirely new character, Robert Frobisher, a young composer in the 1930s working with a crippled aging composer as a sort of apprentice. Frobisher writes letters to his distant lover—both his letters and his lover are plot devices in the third story, a 70s mystery novel focusing on the stouthearted journalist Luisa Rey, who attempts to get to the bottom of a corporate conspiracy.

The first story is from the perspective of the attorney Adam Ewing on a Pacific ship in the 1800s, writing his experiences in his journal. The journal stops midway and picks up with an entirely new character, Robert Frobisher, a young composer in the 1930s working with a crippled aging composer as a sort of apprentice. Frobisher writes letters to his distant lover—both his letters and his lover are plot devices in the third story, a 70s mystery novel focusing on the stouthearted journalist Luisa Rey, who attempts to get to the bottom of a corporate conspiracy.

Recent Comments