Hello again, class.

I’m still a little surprised that I was able to read Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World in high school—at the time, it was the most sexually explicit required reading that had ever crossed my path. But I had a teacher who made it clear that this was an adult novel . . . it wouldn’t be fun or funny. It would be challenging and disturbing, and probably raise more questions than it could answer. In another teacher’s hands, I would have written this novel off as weird; but as I read it for his class, and as I reread it over the past few weeks, I realize that this book is one of the few that invited me to read more challenging stories, even if I didn’t like them.

And there are parts of Brave New World I don’t like, but the novel is special for that exact reason. You aren’t supposed to like it because it’s not entertainment . . . it’s a warning.

The society of Brave New World runs on a set of rules that everyone happily follows; for instance, solitary actions are as prohibited as possible, and in sexual terms, everyone belongs to everyone else. Extreme emotions have been all but eradicated with removal of the family unit, genetic modification, psychological conditioning, and a drug called soma. Without extreme emotions—passion, rage, fear, jealousy, misery—all that’s left is a mellow contentment. Between universal happiness and ideals like truth, beauty, or knowledge, the populace has overwhelmingly chosen happiness.

The society of Brave New World runs on a set of rules that everyone happily follows; for instance, solitary actions are as prohibited as possible, and in sexual terms, everyone belongs to everyone else. Extreme emotions have been all but eradicated with removal of the family unit, genetic modification, psychological conditioning, and a drug called soma. Without extreme emotions—passion, rage, fear, jealousy, misery—all that’s left is a mellow contentment. Between universal happiness and ideals like truth, beauty, or knowledge, the populace has overwhelmingly chosen happiness.

And that’s the setting for a rather depressing story, told from the perspective of a handful of individuals in a society where individuals shouldn’t exist. Bernard Marx is the catalyst for the plot—a man shorter than those he is genetically similar to, and therefore made an outsider. He is simple and somewhat shallow, but by being an outsider, he refuses to medicate himself for happiness and wishes society were different. His friend, Helmholtz Watson, is an outsider because of his affinity for poetry—the happiness of their society begins to wear itself thin for him, causing him to challenge social norms for the sake of the beauty of language.

Author Aldous Huxley

But the real outsider is John the Savage, a man born in one of the few Savage Reservations left that are not “civilized” like the rest of the world. His mother was a woman from civilization, but she became trapped visiting the reservation and was left there, unexpectedly pregnant with John. He grew up with a different skin color from everyone else in the reservation, so he had been an outsider his whole life—then the opportunity arose to visit civilization, as a scientific and social experiment. But he soon learns that the “brave new world” of civilization is terrible, where adults act like children, morality and freedom are all but stripped away, and humanity is weighed down under machines and medication.

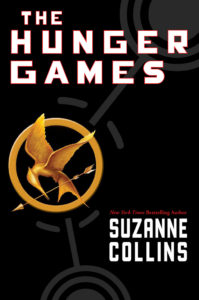

Huxley’s novel portrays less of a dystopia and more of a parodied utopia; there’s a clear distinction. A dystopia is inherently bad, like 1984 or The Hunger Games, where it’s clear people are suffering due to humanity’s mistakes. But Brave New World actually represents a utopia—an almost unrealistically happy society, without war, poverty, famine, misery, or burden. The only person who cannot bear this society is John, who grew up apart from it.

1984 is about a regime holding power and using ideology, propaganda, and torture to subdue threats . . . humanity’s enemy is more powerful than ever, but it’s the same enemy: an upper class with all the power. Brave New World might even be scarier, because there is no enemy. Humanity simply gave up, surrendered to happiness. All the things we like to think make humanity good—art, morality, intelligence, curiosity, passion . . . all replaced by peace. A numbing, terrifying global peace.

1984 is about a regime holding power and using ideology, propaganda, and torture to subdue threats . . . humanity’s enemy is more powerful than ever, but it’s the same enemy: an upper class with all the power. Brave New World might even be scarier, because there is no enemy. Humanity simply gave up, surrendered to happiness. All the things we like to think make humanity good—art, morality, intelligence, curiosity, passion . . . all replaced by peace. A numbing, terrifying global peace.

Brave New World is a warning, but not like most dystopian novels, warning us against threats to society. It’s warning to us that if our everlasting search for happiness and comfort continue, we may gain peace, but we will lose what makes us human.

Nothing hits this point more at home than the many Shakespeare references throughout the novel. Shakespeare has been completely removed from this society, because his words are too beautiful and evocative. His stories of revenge, passion, tragedy, and love cause too much instability to the stable World State, so his works cannot be allowed to exist in society.

A Portrait of William Shakespeare

But in the reservation, John finds one of the last remaining copies of The Complete Works of William Shakespeare, which he uses at a young age to learn how to read. His attraction to Lenina Crowne in the civilized world becomes reminiscent of Romeo and Juliet, while his contemplation of suicide is mirrored in Hamlet‘s “To be or not to be” soliloquy. Most importantly, the title of the book comes from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, which John uses to describe civilization when he sees it for the first time: “O, wonder! How many goodly creatures are there here! How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world, that has such people in’t!”

And that, possibly more than anything else, it what makes this future so horrible. To have happiness, we have to get rid of Shakespeare . . . as well as any other good story, along with God and religion, scientific discovery, and anything else that doesn’t serve the greater purpose of providing comfort and stability for society. Welcome to the brave new world.

I honestly don’t like thinking about this. At least with 1984, I can see that abuse of power is something that has always happened and will continue to happen—the current state of the political world does nothing to convince me that that will ever change. But this . . . Huxley’s novel is simply messed up, and I can’t stand the possibility that humanity might surrender itself completely. This is scarier than any horror I can think of.

So I’m just going to move on to the next novel. Hopefully, students, you feel better about this than I do. I’ve got nothing.

Next up, I’m reading Wuthering Heights, another somewhat depressing story, but at least it comes with a better ending!

Until then, be careful with your happiness and beware the future.

Prof. Jeffrey

The society of Brave New World runs on a set of rules that everyone happily follows; for instance, solitary actions are as prohibited as possible, and in sexual terms, everyone belongs to everyone else. Extreme emotions have been all but eradicated with removal of the family unit, genetic modification, psychological conditioning, and a drug called soma. Without extreme emotions—passion, rage, fear, jealousy, misery—all that’s left is a mellow contentment. Between universal happiness and ideals like truth, beauty, or knowledge, the populace has overwhelmingly chosen happiness.

The society of Brave New World runs on a set of rules that everyone happily follows; for instance, solitary actions are as prohibited as possible, and in sexual terms, everyone belongs to everyone else. Extreme emotions have been all but eradicated with removal of the family unit, genetic modification, psychological conditioning, and a drug called soma. Without extreme emotions—passion, rage, fear, jealousy, misery—all that’s left is a mellow contentment. Between universal happiness and ideals like truth, beauty, or knowledge, the populace has overwhelmingly chosen happiness.

1984 is about a regime holding power and using ideology, propaganda, and torture to subdue threats . . . humanity’s enemy is more powerful than ever, but it’s the same enemy: an upper class with all the power. Brave New World might even be scarier, because there is no enemy. Humanity simply gave up, surrendered to happiness. All the things we like to think make humanity good—art, morality, intelligence, curiosity, passion . . . all replaced by peace. A numbing, terrifying global peace.

1984 is about a regime holding power and using ideology, propaganda, and torture to subdue threats . . . humanity’s enemy is more powerful than ever, but it’s the same enemy: an upper class with all the power. Brave New World might even be scarier, because there is no enemy. Humanity simply gave up, surrendered to happiness. All the things we like to think make humanity good—art, morality, intelligence, curiosity, passion . . . all replaced by peace. A numbing, terrifying global peace.

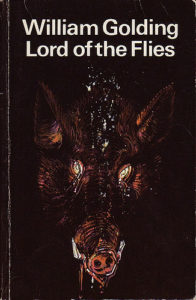

It’s a basic concept of a story: a group of boys is involved in a plane crash on a deserted island, and there are no grown-ups to lead them. They start out well enough, organizing themselves, electing a leader, establishing a hunting team—but a childish tension erodes it all. To top it off, they start to imagine a beast somewhere on the island, that it may be hunting them and planning to kill them all. Their fear and resentment against each other soon become hatred, anger, revenge, and eventually murder.

It’s a basic concept of a story: a group of boys is involved in a plane crash on a deserted island, and there are no grown-ups to lead them. They start out well enough, organizing themselves, electing a leader, establishing a hunting team—but a childish tension erodes it all. To top it off, they start to imagine a beast somewhere on the island, that it may be hunting them and planning to kill them all. Their fear and resentment against each other soon become hatred, anger, revenge, and eventually murder.

There is one other boy who deserves mentioning: Simon, the quiet boy younger than Jack, Ralph, and Piggy, serving as a kind of bridge between the “biguns” and the “littluns.” He’s smart—not in the same way as Piggy, who is rational and critical, but in a more creative and reflective way. Simon doesn’t say or do much, but he is the only boy on the island who sees and understands who (or what) the Lord of the Flies really is.

There is one other boy who deserves mentioning: Simon, the quiet boy younger than Jack, Ralph, and Piggy, serving as a kind of bridge between the “biguns” and the “littluns.” He’s smart—not in the same way as Piggy, who is rational and critical, but in a more creative and reflective way. Simon doesn’t say or do much, but he is the only boy on the island who sees and understands who (or what) the Lord of the Flies really is. The Hunger Games Trilogy didn’t get the same advantage—the first installment was published in 2008, and the final installment in 2010, a year before the official list was released. If the list had been made later, I honestly believe this series would have been included. But, as always, let’s talk about why.

The Hunger Games Trilogy didn’t get the same advantage—the first installment was published in 2008, and the final installment in 2010, a year before the official list was released. If the list had been made later, I honestly believe this series would have been included. But, as always, let’s talk about why.

Recent Comments