Good morning, class.

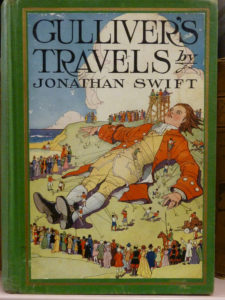

I’ve been comparing Gulliver’s Travels (my other most recent read from the list) with Don Quixote, and I’ve come away with a broad conclusion on both. On my post about Gulliver’s Travels, I wrote that that Gulliver’s Travels is all a dark joke at society’s and humanity’s expense. If Gulliver’s Travels is literature’s dark joke, then Don Quixote is its lighthearted one—a series of recurring comedy sketches centered on a madman who thinks he’s a knight and the hopeless fool who tags along as his squire.

I’ve been comparing Gulliver’s Travels (my other most recent read from the list) with Don Quixote, and I’ve come away with a broad conclusion on both. On my post about Gulliver’s Travels, I wrote that that Gulliver’s Travels is all a dark joke at society’s and humanity’s expense. If Gulliver’s Travels is literature’s dark joke, then Don Quixote is its lighthearted one—a series of recurring comedy sketches centered on a madman who thinks he’s a knight and the hopeless fool who tags along as his squire.

Despite that simple premise, Don Quixote is more complicated than that. The main character, whose name isn’t even Quixote, starts as an ordinary Spanish man with an ordinary life. But he reads a little too much about the knights of the age of chivalry, and starts to think he’s a knight himself, adopting the name Don Quixote. What follows is a carefully orchestrated parody of knighthood, romantic quests, and the world of literature.

Don Quixote charging at the windmills.

The relationship between Quixote and his squire, Sancho Panza, reminds me a lot of the relationship between Frodo and Samwise in The Lord of the Rings—both relationships come from the same place: the knight/squire relationship of older works of literature like the King Arthur stories and Beowulf. But Quixote and Sancho don’t fit these roles so easily. Quixote acts like the noble knight he thinks he is, which usually just gets him into trouble; and Sancho is simply along for the ride, not half as dedicated as he imagines and too much of a buffoon to know any better. Comedy ensues.

There are several moments that stand out—the most famous one is likely the episode where Quixote attacks a set of windmills, thinking that they are a field of giants with large swinging arms, despite Sancho’s explanations of reality. The comedy tends to remain in this area, where Quixote misreads a common occurrence as a knightly adventure, and Sancho has little choice but to go along with it.

Portrait of Author Miguel de Cervantes (1547-1615)

Author Miguel de Cervantes has more than a touch of Shakespeare about him. The dialogue is witty, with double entendres that survive translation and clever twists that make the old feel new. The meta-jokes are hilarious additions that stand the test of time (about 400 years). What’s more, since Don Quixote is considered one of the earliest novels ever written, it’s clear that Don Quixote paved the way for an entire category of literature like nothing else before it—that’s fairly Shakespearean. Cervantes was one of the story-telling geniuses of his time, and his writing is one of the big reasons Don Quixote made the list.

That said, the experience of reading it wasn’t 100% enjoyable, if only because I had to trudge through it. It’s not easy to read, and I knew it wouldn’t be as I started—the same thing happens with Shakespeare. In reading Don Quixote, there was always so much happening within so many different layers of language that most of it passed me by. It takes a steadier mind than mine to dive headfirst into all that makes Don Quixote special, and as I’m someone who prides himself on his joy of reading, it doesn’t bode well for the poor soul who reads this thinking “well, it’s one of the 50 books I’m supposed to read before I die, so I guess I’ll try it.”

But that’s my mild complaint—that I didn’t feel smart enough to catch everything that happened. I’ve already explained in other posts that there are books that don’t belong on the list, but Don Quixote isn’t one of them. Don Quixote is hilarious, thoughtful, and a perfect example of good literature from its era, and that’s the best reason it made the list.

I’m jumping forward in time and reading Ernest Hemingway next—his collection of short stories, Men Without Women. I have a lot of thoughts on Hemingway, as well as this particular choice for the list (as opposed to his several other more famous novels), but I’ll save those thoughts for next time.

Until then,

Prof. Jeffrey

Welcome back, class.

Welcome back, class.

Recent Comments