Hello again, class.

James Joyce’s Ulysses features prominently on the 50-books bookmark, for good reason (more on that another time). But what bothers me is that Ulysses is a sequel—one of the main characters, Stephen Dedalus, is the main character of Joyce’s original groundbreaking work A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. I won’t have any of this reading-out-of-order nonsense, so Portrait of the Artist needs to be spoken for.

Granted, I’m not the first to admit that Ulysses is the better of the two. It has stronger characters and fewer sermons. But Ulysses wouldn’t have been possible without Portrait of the Artist. And since millions of books wouldn’t have been possible without Ulysses, I think Joyce’s first novel has earned a little spotlight.

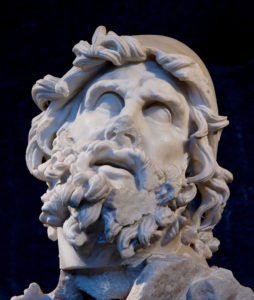

Portrait of the Artist tells the coming-of-age story of Stephen Dedalus, a boy in late 19th century Ireland with a creative streak and a complicated life. We get to see him transform from a mystified little boy to a questioning teenager, and then to an adult making the terrifying decision to be himself, regardless of the consequences. He loses respect for his father, puts his family in financial struggle, rejects religion and Irish nationality . . . and doesn’t compromise.

The mastery of this novel is not the story—this is a story anyone could tell. What makes it masterful is it’s original style, which any reader encounters with the opening lines: “Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road and this moocow that was coming down along the road met a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo . . .”

It’s confusing, that’s for sure. It causes quite the double-take.

Some of you know that this is called stream-of-consciousness, where the author takes the characters inner thoughts and dumps them on the page as they are. Most authors do this within the rules of grammar, but Joyce didn’t have time for rules. Just like Stephen’s struggle to be himself, despite the expectations around him, Joyce denied the expectations a novelist should follow.

These opening lines are the inner thoughts of Stephen as a child, with a glorified version of his father telling him a story. The “moocow” is the combination of the sound with the animal (imagine asking a child what noise a cow makes, and they answer “MOOOO;” in their mind, they don’t distinguish the noise from the animal . . . they are the same thing until they’re old enough to tell the difference). And without commas or periods, the run-on feels like a knowledge dump, which is how Joyce portrays the mind of a child—unbound by rules.

As Stephen grows up, his mind develops, and his thoughts become more structured. He uses a stronger vocabulary and a more refined grammar. Not that it makes his style much easier to follow—we are still inside the mind of a temperamental artist.

Which is why the title has that specific word artist. Stephen isn’t just anyone—his creative tendencies are a part of his core. He finds himself obsessed with the beauty of words, and his imagination is incredible as it unfolds (my favorite moment is when he is a boy: he thinks of different colors of roses and imagines a rose that’s green).

Stephen is a bit too angst-y to be likable, but he is still a strong character. And when we see him again in Ulysses . . . well, we’ll get there when we get there.

I’m still reading The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon, and it’s worth mentioning the similarities it has with Portrait of the Artist. The main character is hinted to have autism, so he sees everything differently—many people claim that James Joyce had some form of autism, which may have led to his particular stylistic approach. While the novels are very different, the stylistic connections make The Curious Incident a kind of spiritual sequel to Joyce’s writing.

That being said, Haddon’s book is a lot easier. If Joyce isn’t your thing, The Curious Incident is a touch easier on the brain cells. But more on that next week.

Until then,

Prof. Jeffrey

Recent Comments