Good morning, class, and down with Big Brother.

I enjoyed 1984 much more reading it the second time…it must have something to do with not being in high school anymore. I’m sure my high school experience was better than others, but when my English teacher helped us understand George Orwell by comparing our student news videos to the Two Minutes Hate and the manipulation of the media, a wee bit of paranoia started to set in. I’ve been a skeptical person since.

Paranoia aside, 1984 is very enlightening. Rereading it now, in the heightened political tension of our country, is particularly notable. I won’t pretend to understand the political spectrum, but I do understand ethics, and there are some unethical happenings in these United States, let me tell you.

But before jumping into ethics and politics, I want to jump into the novel itself, and get at why it’s worth reading.

A Summary

For those of you that don’t know, 1984 is a novel from the late 1940s, portraying a dystopian future set in or around the year 1984. We follow Winston Smith, a regular enough guy, who spends his days updating documents in service to the Party (the ruling political body); but in his mind, he gives us the scoop on the terrible world he lives in. The Party enforces total order and removes any and all traces of rebellion or revolution; telescreens and microphones are everywhere, destroying privacy; egregious lies are perpetuated, the most notable of which is a fictional, decades-long war used to distract the masses and enforce rations; and Big Brother, the terrifying face that looms over everything, holds all of the political power.

For those of you that don’t know, 1984 is a novel from the late 1940s, portraying a dystopian future set in or around the year 1984. We follow Winston Smith, a regular enough guy, who spends his days updating documents in service to the Party (the ruling political body); but in his mind, he gives us the scoop on the terrible world he lives in. The Party enforces total order and removes any and all traces of rebellion or revolution; telescreens and microphones are everywhere, destroying privacy; egregious lies are perpetuated, the most notable of which is a fictional, decades-long war used to distract the masses and enforce rations; and Big Brother, the terrifying face that looms over everything, holds all of the political power.

In the privacy of Winston’s own mind, we find freedom. He can think what he wants, but that is dangerous: if his face, eyes, or body language reveal his thoughts to the ever-watchful telescreens, he will be caught committing thoughtcrime (any insurgent or disloyal thought) and for that he can be executed. So he is always mentally suppressing himself, forcing everything but the inner sanctum of his mind to walk, talk, and act like any other Party supporter would. He can only hope that this is enough to maintain his individuality.

The book is divided in three parts. In Part One, we see a handful of days in Winston’s life, and what he does to survive. In Part Two, his life is turned around by a woman he meets, who has a similar hate for the Party, and they begin an affair. I can’t give away much of Part Three without spoiling the ending, but suffice it to say that his affair leads him further inside the Party’s inner workings than he’s ever been before.

A Commentary on Individuality

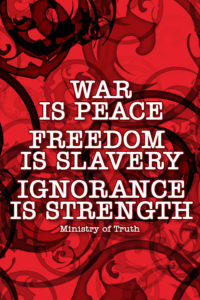

There are many ideas guiding the novel, but Winston’s individuality is the most important one. The fact that he has his own memories, his own thoughts, his own feelings… it means that he still has his humanity. The Party is, ideologically, a group mind; they believe that reality exists only in the collective mind, so if everyone agrees that something is true, then it is true. If there were only two people on the planet and they both truly believed that they had the ability to fly, then that was true, regardless of whether they actually lifted off the ground. External reality is invalid.

There are many ideas guiding the novel, but Winston’s individuality is the most important one. The fact that he has his own memories, his own thoughts, his own feelings… it means that he still has his humanity. The Party is, ideologically, a group mind; they believe that reality exists only in the collective mind, so if everyone agrees that something is true, then it is true. If there were only two people on the planet and they both truly believed that they had the ability to fly, then that was true, regardless of whether they actually lifted off the ground. External reality is invalid.

I think Winston is less concerned about the idea that reality is subjective, and more interested salvaging the part of him that mentally disagrees with the Party’s ideology. He wants to maintain his self by distancing it from the Party, but they have all the power, so he has to do that without them knowing, making him a sheep in wolf’s clothing. He can see his impending death, so his life is about putting that off for as long as possible, which is only worthwhile because he remains himself, at his own peril.

This may be a drastic view on Orwell’s part, but it is a dark mirror of the world we live in. Historically speaking, we have less privacy than ever before. There are drones and cameras and microphones everywhere, and there is the Internet, where social media opens up every biographical floodgate and where bloggers post at their every whim (don’t worry, I don’t do that; I may be whimsical, but I’m practically whim-less; impulsiveness is my bane). There is an incredible power to the technology we have access to, and that technology can be extremely costly to our lives and our humanity, if we aren’t careful.

But imagine, for a second, what reality looks like if exactly that happens—if we aren’t careful, if we are reckless, if we are even destructive. This novel reveals that there are two options—recklessness and order, or as I like to call them, freedom and peace. And, if you’ll allow the genre leap, these same options are offered in a much more contemporary story…Captain America: Civil War.

The Comics’ Relief

Well, I seem to have caught the attention of comic book fans in the back of the class—thank you for joining us. Yes, I am comparing George Orwell’s 1984 to the blockbuster hit of the year, Captain America: Civil War, at least in part because it continues Orwell’s political and ethical dialogue. It’s not a perfectly clean connection, but a very similar issue is played out between our opposing heroes, Steve Rogers’ Captain America and Tony Stark’s Iron Man.

Well, I seem to have caught the attention of comic book fans in the back of the class—thank you for joining us. Yes, I am comparing George Orwell’s 1984 to the blockbuster hit of the year, Captain America: Civil War, at least in part because it continues Orwell’s political and ethical dialogue. It’s not a perfectly clean connection, but a very similar issue is played out between our opposing heroes, Steve Rogers’ Captain America and Tony Stark’s Iron Man.

Stark, having been partly responsible for the almost-destruction of Earth, has given up. He thinks superpowered people should answer to someone before things get out of hand, and he’s lumped himself into the group that needs to be “put in check.” He can’t stand to be responsible for more loss of life. Rogers starkly opposes this (don’t you love a good pun); when leaders start putting superheroes on a register, they dangerously approach the death of freedom. He wants to save people, and if he signs over his allegiance to a government body, he may not get the chance to do what he believes is right. He trusts his own abilities and his own morals more than those of a government.

The irony is not lost here—Captain America is opposing the American government. Well, surprise, that’s because America is its people, not its ruling body. Rogers’ decision is about freedom, and not letting the fear of loss of life get in the way of that. Stark, on the other hand, is giving into his own fears, and his guilt. He’s willing to sacrifice freedom for safety, where Rogers isn’t. Stark wants peace and order, and he’ll do what it takes to get it.

A Political, Ethical Question

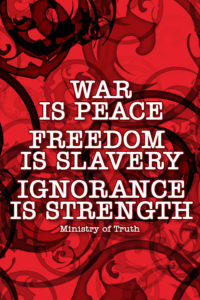

As terrible as the world of 1984 sounds, it is a peaceful world. Crime is dealt with before it happens, the ruling body stays in power unquestionably, and noble ideas about freedom and justice won’t dare topple the order that has been established. It is a deadly, terrifying peace, at the cost of freedom. Winston Smith, our aging, frail hero, is maintaining his individuality—his freedom to be himself—endangering his life at every passing moment. The novel asks an unanswerable question of politics and ethics—what’s more important, freedom or peace?

As terrible as the world of 1984 sounds, it is a peaceful world. Crime is dealt with before it happens, the ruling body stays in power unquestionably, and noble ideas about freedom and justice won’t dare topple the order that has been established. It is a deadly, terrifying peace, at the cost of freedom. Winston Smith, our aging, frail hero, is maintaining his individuality—his freedom to be himself—endangering his life at every passing moment. The novel asks an unanswerable question of politics and ethics—what’s more important, freedom or peace?

Even worse, it gives us an answer we don’t like: external reality is invalid, the Party’s truth is the only truth, and the individual’s thoughts, memories, and feelings are subjective. The Party has power and truth, and the individual’s denial of it makes the individual an enemy of the state. Everything said can be disproved, denied, manipulated…everything thought is a lie because the individual mind is a lie, and the collective mind is the only truth.

As brutally heart-wrenching as Captain America: Civil War is, 1984 takes “brutal” to a whole new level.

If you decide to try reading 1984, I recommend you come at it with determination. The language is difficult to muddle through, and at its worst, it is a tangent on ideological concepts. Orwell uses the story to explain political ideas, and he does it because the story is important, but it doesn’t seem as important to him as the political ideas. Even so, I can’t imagine that there’s a better way to tell this kind of story, which definitely needs to be told.

Your homework: answering another unanswerable question. If you had the choice between freedom and peace, what would you choose? I’ve obviously landed on the side of freedom, as have George Orwell and Captain America, but this is such a broad topic that we can easily be proven wrong. Is it more important to be free, regardless of the cost to peace? Or is it more important to have a lasting peace, sacrificing freedom in the process? Leave a reply in the comments, and bonus points for anyone who ties in actual politics to a political question.

Up next, I’m reading Hamlet. Time for some Oedipal complexes and existential crises!!

Prof. Jeffrey

Good morning class.

Good morning class.

For those of you that don’t know, 1984 is a novel from the late 1940s, portraying a dystopian future set in or around the year 1984. We follow Winston Smith, a regular enough guy, who spends his days updating documents in service to the Party (the ruling political body); but in his mind, he gives us the scoop on the terrible world he lives in. The Party enforces total order and removes any and all traces of rebellion or revolution; telescreens and microphones are everywhere, destroying privacy; egregious lies are perpetuated, the most notable of which is a fictional, decades-long war used to distract the masses and enforce rations; and Big Brother, the terrifying face that looms over everything, holds all of the political power.

For those of you that don’t know, 1984 is a novel from the late 1940s, portraying a dystopian future set in or around the year 1984. We follow Winston Smith, a regular enough guy, who spends his days updating documents in service to the Party (the ruling political body); but in his mind, he gives us the scoop on the terrible world he lives in. The Party enforces total order and removes any and all traces of rebellion or revolution; telescreens and microphones are everywhere, destroying privacy; egregious lies are perpetuated, the most notable of which is a fictional, decades-long war used to distract the masses and enforce rations; and Big Brother, the terrifying face that looms over everything, holds all of the political power. There are many ideas guiding the novel, but Winston’s individuality is the most important one. The fact that he has his own memories, his own thoughts, his own feelings… it means that he still has his humanity. The Party is, ideologically, a group mind; they believe that reality exists only in the collective mind, so if everyone agrees that something is true, then it is true. If there were only two people on the planet and they both truly believed that they had the ability to fly, then that was true, regardless of whether they actually lifted off the ground. External reality is invalid.

There are many ideas guiding the novel, but Winston’s individuality is the most important one. The fact that he has his own memories, his own thoughts, his own feelings… it means that he still has his humanity. The Party is, ideologically, a group mind; they believe that reality exists only in the collective mind, so if everyone agrees that something is true, then it is true. If there were only two people on the planet and they both truly believed that they had the ability to fly, then that was true, regardless of whether they actually lifted off the ground. External reality is invalid. Well, I seem to have caught the attention of comic book fans in the back of the class—thank you for joining us. Yes, I am comparing George Orwell’s 1984 to the blockbuster hit of the year, Captain America: Civil War, at least in part because it continues Orwell’s political and ethical dialogue. It’s not a perfectly clean connection, but a very similar issue is played out between our opposing heroes, Steve Rogers’ Captain America and Tony Stark’s Iron Man.

Well, I seem to have caught the attention of comic book fans in the back of the class—thank you for joining us. Yes, I am comparing George Orwell’s 1984 to the blockbuster hit of the year, Captain America: Civil War, at least in part because it continues Orwell’s political and ethical dialogue. It’s not a perfectly clean connection, but a very similar issue is played out between our opposing heroes, Steve Rogers’ Captain America and Tony Stark’s Iron Man. As terrible as the world of 1984 sounds, it is a peaceful world. Crime is dealt with before it happens, the ruling body stays in power unquestionably, and noble ideas about freedom and justice won’t dare topple the order that has been established. It is a deadly, terrifying peace, at the cost of freedom. Winston Smith, our aging, frail hero, is maintaining his individuality—his freedom to be himself—endangering his life at every passing moment. The novel asks an unanswerable question of politics and ethics—what’s more important, freedom or peace?

As terrible as the world of 1984 sounds, it is a peaceful world. Crime is dealt with before it happens, the ruling body stays in power unquestionably, and noble ideas about freedom and justice won’t dare topple the order that has been established. It is a deadly, terrifying peace, at the cost of freedom. Winston Smith, our aging, frail hero, is maintaining his individuality—his freedom to be himself—endangering his life at every passing moment. The novel asks an unanswerable question of politics and ethics—what’s more important, freedom or peace?

Recent Comments