Good morning, class.

Good morning, class.

The Great Gatsby is timeless—timeless because the story and it’s themes are still relevant; timeless because Gatsby is an icon of class struggle and the American dream; timeless because the language is unique and poetic; timeless because the narrative always has more to offer than what is seen on the page; and timeless because it not only represents people from 1920’s America, but also people all time periods, all over the world, who suffer from greed, love, and the past coming back to haunt us.

I really like this novel.

For those not in the know: The Great Gatsby follows narrator Nick Carraway, who tells us the story of Jay Gatsby, a mysterious figure with a complex past. He throws lavish parties that he doesn’t attend, brags about his seemingly made-up time spent at Oxford college, and is obsessed with Daisy Buchanan—a young wife and mother who knew him long ago. Daisy and Jay loved each other, but Gatsby went off to war, and Daisy settled for Tom—a wealthy athletic man who peaked young, and who cheats on his wife regularly.

Sam Waterston and Robert Redford as Nick Carraway and Jay Gatsby in The Great Gatsby (1974)

And then, Gatsby returns, and upends the Buchanans’ life. Nick depicts the turmoil in glorious detail; the affairs, the illegal money-making, the immense sadness and rage these people cause each other, and the fateful end. Every moment seems to be made out of poetry. The story is as thrilling as it is beautiful, and that’s what makes it special—and that’s why it makes the list.

Let’s talk about some of what makes it special: The Great Gatsby is a “summer” novel, partly because the events take place over the course of a summer. It’s also short and easy to read, not like most other “great” novels. But it’s not simple . . . it’s simply as thought-provoking as the reader is willing to think. It has enough layers to peel back for the most obsessive literary critics, but it still has enough of a surface story to be interesting to the common reader.

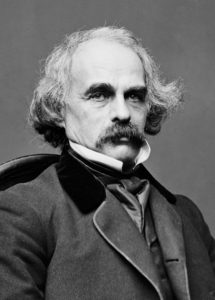

F. Scott Fitzgerald, author of The Great Gatsby.

And underneath the surface story is an interpretation for each and every reader. As soon as Nick’s judgement of the events is called into question—right about the time when he says “I’m inclined to reserve all judgements”—every statement he makes could be a rearrangement of the truth. If that doesn’t prove his unreliability, then his claim that he is “one of few honest people [he has] ever known” definitely does, after he lies a few times in later chapters.

There’s always something new to uncover with The Great Gatsby—it’s almost Shakespearean. But it’s not nearly as old and distant as Shakespeare; at almost one hundred years old, it still feels current and readable, and it’s as pleasant as it is mind-blowing. That’s more than enough reason to make the list.

Up next, I’m taking it easy with The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame, a classic of children’s literature. I’m sure I’ll enjoy it—I need some talking animals.

Until then, have a good week.

Prof. Jeffrey

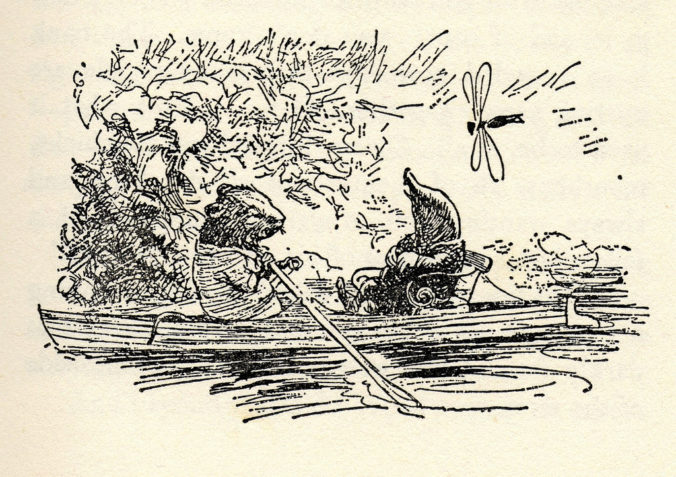

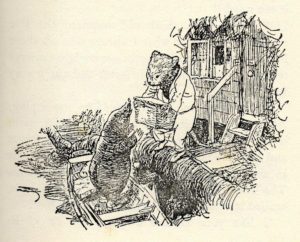

The Wind in the Willows is one of the most pleasant stories I’ve read in a long time. It’s short and entertaining, full of talking animals on crazy adventures, and never shallow enough to lose suspension of disbelief. More importantly, it’s a children’s story—easily what a parent would read to their children every night, which means unlike most novels on the 50-books list, this actually is something everyone should (and could) read.

The Wind in the Willows is one of the most pleasant stories I’ve read in a long time. It’s short and entertaining, full of talking animals on crazy adventures, and never shallow enough to lose suspension of disbelief. More importantly, it’s a children’s story—easily what a parent would read to their children every night, which means unlike most novels on the 50-books list, this actually is something everyone should (and could) read.

I do still question it’s inclusion on the list. The excellent writing and the portrayal of a child’s fantasy dreamworld is already on the list—

I do still question it’s inclusion on the list. The excellent writing and the portrayal of a child’s fantasy dreamworld is already on the list—

Good morning, class.

Good morning, class.

Recent Comments