Welcome back, class. It’s time to weep for the end of innocence.

A while back, I wrote about The Shining by Stephen King, claiming that it should be on the 50-books list as a representative of the horror genre, because horror didn’t feature much on the list. After reading William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, I realize that I spoke too soon . . . Lord of the Flies is one of the spookiest, goriest, most uncomfortable novels I’ve read in a long time, and that’s clearly one of the reasons it made the list.

It’s a basic concept of a story: a group of boys is involved in a plane crash on a deserted island, and there are no grown-ups to lead them. They start out well enough, organizing themselves, electing a leader, establishing a hunting team—but a childish tension erodes it all. To top it off, they start to imagine a beast somewhere on the island, that it may be hunting them and planning to kill them all. Their fear and resentment against each other soon become hatred, anger, revenge, and eventually murder.

It’s a basic concept of a story: a group of boys is involved in a plane crash on a deserted island, and there are no grown-ups to lead them. They start out well enough, organizing themselves, electing a leader, establishing a hunting team—but a childish tension erodes it all. To top it off, they start to imagine a beast somewhere on the island, that it may be hunting them and planning to kill them all. Their fear and resentment against each other soon become hatred, anger, revenge, and eventually murder.

Ralph, the boy elected as “chief,” is somewhat charismatic, and older than most of the boys there—in the boys’ eyes, this makes him an excellent leader. Jack, the boy almost elected, is similar to Ralph at first, but he ultimately resents not being elected; he divides the group between those who voted for him and Ralph, and releases his inner savage when things don’t go his way. Then there’s Piggy: an overweight asthmatic boy who wears glasses, and who is never once taken seriously, even though he is clearly the smartest of the group. Between these three characters, this group of boys is transformed into a group of dangerous killers.

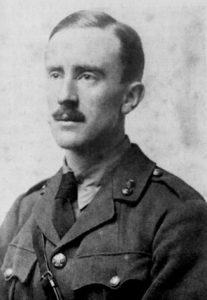

Author William Golding

If these characters weren’t children, the story would still work remarkably well. They disagree about the best methods of survival, hesitate to abandon rules, and eventually succumb to their more primal instincts. Part of Golding’s message is that the human race functions like this, on a larger scale . . . that within even the most composed and humane individuals lies a beast, waiting to lash out at the opportune moment. If a group of fully grown adults were trapped on this island, the societal breakdown might have taken longer, but it would have happened all the same (i.e., the TV show Lost).

But the simple fact that these are children makes all the difference. As Jack slips slowly into vengeance and savagery, it’s easy to hate and fear him, until you get the gentle reminder that he’s no older than 12. But he is wrapped up in the same horror as the rest of them—within him lies the beast within all of humanity, and his power over the others causes it to lash out ravenously.

There is one other boy who deserves mentioning: Simon, the quiet boy younger than Jack, Ralph, and Piggy, serving as a kind of bridge between the “biguns” and the “littluns.” He’s smart—not in the same way as Piggy, who is rational and critical, but in a more creative and reflective way. Simon doesn’t say or do much, but he is the only boy on the island who sees and understands who (or what) the Lord of the Flies really is.

There is one other boy who deserves mentioning: Simon, the quiet boy younger than Jack, Ralph, and Piggy, serving as a kind of bridge between the “biguns” and the “littluns.” He’s smart—not in the same way as Piggy, who is rational and critical, but in a more creative and reflective way. Simon doesn’t say or do much, but he is the only boy on the island who sees and understands who (or what) the Lord of the Flies really is.

After Jack’s hunting party slays a pig, they victoriously stake the pig’s head on a sharpened stick and post it in the ground. As they leave, Simon is enamored by it and stays behind, staring at the pig’s gory smile and hearing nothing but the cloud of flies attacking the bloody corpse. And then the scene becomes a mirage, or maybe a nightmare, as the pig’s head—the Lord of the Flies—begins to speak to Simon, naming himself the beast the children are all afraid of. The Lord of the Flies is the Devil itself.

Simon is the only boy who realizes that the beast they are all so afraid of is harmless, because it lies within—the only one who learns the message Golding is writing. The Lord of the Flies is a part of all of us, and all it needs is a push to escape the confines of something as simple as society.

In continuing the theme of savagery, I’m following up Lord of the Flies with Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. I’m surprised that the list features 1984 and Brave New World together, both heavily influential dystopian novels. I look forward to discussing the differences between them.

Until then, enjoy your week. And keep an eye out for your inner Lord of the Flies.

Prof. Jeffrey

Capote and Lee went researching after the murders were committed to tell the story: Herbert and Bonnie Clutter, and their two youngest children Nancy and Kenyon, were killed on November 15, 1959 by Dick Hickock and Perry Smith. The novel follows the murderers, the victims, and the rest of Holcomb leading up to and following the crime.

Capote and Lee went researching after the murders were committed to tell the story: Herbert and Bonnie Clutter, and their two youngest children Nancy and Kenyon, were killed on November 15, 1959 by Dick Hickock and Perry Smith. The novel follows the murderers, the victims, and the rest of Holcomb leading up to and following the crime.

Good morning, class.

Good morning, class.

Unlike The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit is a children’s novel—the story is simpler, with the same feel as The Wind in the Willows or Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. But it doesn’t sacrifice the depth of Tolkien’s fantasy world by being kid-friendly; Middle-Earth is more extravagant and complete than Narnia, Neverland, and Oz combined. The only difference in The Hobbit is that it’s for all ages.

Unlike The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit is a children’s novel—the story is simpler, with the same feel as The Wind in the Willows or Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. But it doesn’t sacrifice the depth of Tolkien’s fantasy world by being kid-friendly; Middle-Earth is more extravagant and complete than Narnia, Neverland, and Oz combined. The only difference in The Hobbit is that it’s for all ages.

Recent Comments