Happy Black History Month!

I’ve recalibrated my view of Black History Month in recent years. Growing up, my privilege helped me see it as the month to remember the difficulties African Americans used to face. This is mostly the same today—it’s the “used to” that’s changed. What I see now is that the Civil War and Civil Rights Movement were both monumental eras in American history that changed how our laws and leadership treated black lives, and we have yet to solve the issue of racism separately from the law—i.e., the racism within the hearts and minds of American citizens. Nothing helped me understand that more than Claudia Rankine’s Citizen.

Claudia Rankine, author of Citizen: An American Lyric

Citizen: An American Lyric has a perfect excuse for not making the list: it was composed after the list was. Nonetheless, since it’s publication only three years ago, I believe it’s one of the books everyone needs to read before they die.

Citizen is a collage—a hodgepodge of pictures, personal accounts, and nonfiction written like poetry. It’s also a wide variety of perspectives on racism in modern America. Mostly what you’ll find is Rankine’s unique take on moments of racism, where she describes the context to “you” the reader, putting you in the place of the slighted and ignored. She paints the figurative portraits of the man no one will sit next to, the woman listening to complaints about affirmative action as if she’s to blame, and the child ignored and knocked over by a white man.

Reading Citizen is an experience—or, rather, it portrays the experience no one wants to have: the racism she and others have personally felt in a way that’s painfully relatable. She writes of the anger black men and women are stereotyped for, and of the collective sigh built up from all of the moments when racism stung her. More than anything, Rankine proves how different the black experience is from the white in America, with privilege clearly bending toward the white.

Still of Serena Williams at the 2011 U.S. Open in a match she famously lost. Rankine uses part II of Citizen to tell Williams’ story.

No one passage carries more weight than another, but particular attention should be given to the passage on Serena Williams, widely considered the best female tennis player of all time. Rankine delves into Williams’ history with the game of tennis, and the racism in Williams’ most famous matches—how the umpire, intentionally or unintentionally, used Williams’ skin color and stereotyped anger to penalize her in matches she was clearly winning. But whether Williams was winning or losing, her blackness is used against her, and there is no resolution to the racism she faces; the story ends with a white athlete mocking her looks and behavior, and it’s as if that’s the resolution the audience needed . . . the stereotyped image of the best tennis player of all time, minus her black skin.

The word “citizen” appears once in the entire book, toward the end—almost carrying the weight of the entire anthology of racism before it. It seems that, for black Americans, citizenship means moving on from racism . . . letting your feelings go, however attached you are to them (even if they are all you are), and ignoring the racism against you with as much force as white people are ignoring you. That’s how poisoned by racism citizenship has become—as poisoned as America itself. That hasn’t changed since the publication of Citizen—in fact, I would argue that American citizenship has continued to deteriorate from racism in spite of Rankine’s powerful work. Perhaps if more people read it, more people would see what African Americans are seeing.

It’s not easy to read—not only because it speaks to some difficult truths, but also because Rankine’s ambiguous stream-of-consciousness poetry leaves a lot to interpretation—but Citizen is important now. It portrays the difficult truths of now. Rankine’s voice is one we need to hear so that we can change what the world looks like when we step out the door. She doesn’t make it easy because she doesn’t provide political answers to a political question—she only portrays the problem of racism, which she has no solution for. She provides the empathy needed to see injustice, not the tools to fight it, and it’s not fair of us to ask her for both. After all, we’re all citizens, too.

Above: The Slave Ship by Joseph Mallord William Turner. Below: A detail of a slave’s leg from The Slave Ship. Both images appear at the end of Citizen.

A few additional thoughts: In the realm of solving the problem of racism in America, I have no answers. I know brute force doesn’t work, and I know leaving everyone to their own devices doesn’t help much. My best guess is that education and love are the solution—both of which probably only work with the kind of empathy Rankine puts on her readers in Citizen.

Acknowledge your privilege, that’s another big step. Look in the mirror and see what society values—even if it’s a value from bad intentions—and use it to make the world better (not just for you). For starters, the fact that you can read this means you have enough privilege to go around. Reading Citizen is a good place to go next, in my opinion.

Prof. Jeffrey

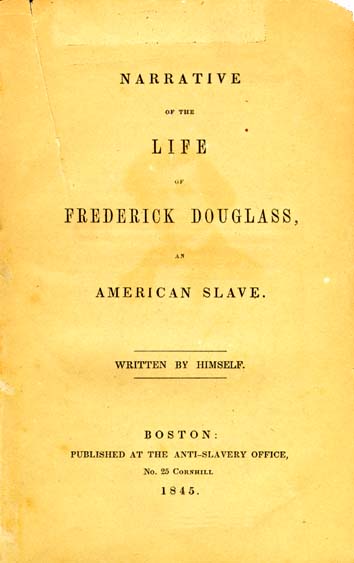

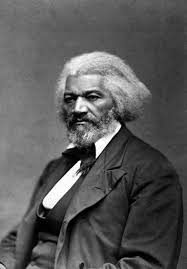

Douglass’ life also has enough historical significance that it should be read whether it’s good or not (it just so happens that it’s good writing as well). The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is an important historical milestone for the abolitionist movement of its time, which forever altered American history through the Civil War, the Civil Rights Movement, and modern race issues we still struggle with today. Like similar nonfiction works, it should be required reading for everyone—it belongs on the list because it helped change the world.

Douglass’ life also has enough historical significance that it should be read whether it’s good or not (it just so happens that it’s good writing as well). The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is an important historical milestone for the abolitionist movement of its time, which forever altered American history through the Civil War, the Civil Rights Movement, and modern race issues we still struggle with today. Like similar nonfiction works, it should be required reading for everyone—it belongs on the list because it helped change the world.

Recent Comments