Good morning, class.

I’ve talked about my favorite poems before (here and here), and today, I’ll do the same with short stories!

This hardly needs explaining—below, I’ve listed some of my personal favorite short stories that I’ve read in literature classes over the years. Some are long enough that they could be considered “novellas,” but that kind of categorization barely matters. What’s listed below are good stories: plain and simple and in chronological order.

-

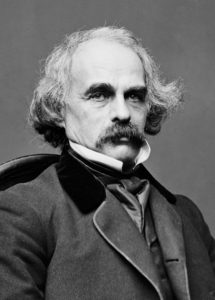

Author Nathaniel Hawthorne

“Young Goodman Brown” by Nathaniel Hawthorne: Nathaniel Hawthorne is probably better known for The Scarlet Letter, but I like his short stories more, and this one is my favorite. It’s critical of religion while using Christian and Satanic imagery to tell the story of Young Goodman Brown’s walk in the woods, where he encounters the devil, sees all his fellow townspeople worship like heathens, and loses his wife, Faith (not-so-subtly). Then it all disappears like a vision, and he’s left alone and forever changed. The story is layered, terrifying, and much more enjoyable than The Scarlet Letter . . . for what that’s worth.

- “The Yellow Wall-paper” by Charlotte Perkins Gillman: The way this story is written—in small, sudden paragraphs that cause an unnerving itch—is what makes it so terrifying, and so great. The narrator is writing to us, against her husband’s wishes (she must be under constant bed rest, because she “suffers” from things like nervousness, frailty, hysteria . . . by which I mean she has an actual mental illness, but has instead been diagnosed with being a woman).

Author Charlotte Perkins Gilman

She writes about their move to a new house, her marriage, and most importantly, the disgusting yellow wallpaper in her bedroom. I won’t give away what happens—it’s too enjoyable to spoil—but suffice it to say the wallpaper is the last straw on her troubled mind.

- “The Wife of His Youth” by Charles W. Chesnutt: Stepping away from horror, this story delves into the politics of post-Civil War America, from the perspective of a leader in a society of more respectable (lighter-skinned) African Americans. Mr. Ryder has worked very hard to gain his reputation and he hides his past carefully—until a less-respectable woman enters his life and disrupts his reputation. It’s a subtle look at racial treatment during the Reconstruction Era, and it makes us aware of the black community of the time, the pride and shame within said community, the masks they still had to wear, and the choices they were faced with.

- “The Dead” by James Joyce: Of course James Joyce makes the list! Before he was over-complicating things with Ulysses, he wrote a relatively standard collection of short stories titled Dubliners, my favorite of which is “The Dead.” The protagonist, Gabriel, is tasked with making a toast at a dinner party, and he debates inwardly what words to use and what poets to quote—cluing us into the political ramifications of the Irish-British conflict at the time. In Gabriel’s relationship with his wife, with close friends, with guests and with strangers, he is torn (just like Mr. Ryder in “The Wife of His Youth”) between two cultures—one that seems brighter and more reputable, but that will never accept his inferiority as an Irishman, and another that would feel like a step backwards from success and reputation. It’s an intricate look at Ireland and its people, and it’s beautifully written.

- “The Balloon” by Donald Barthelme: This one is only kind of a story—it breaks a lot of the rules of storytelling. A mysterious balloon floats loose through a town for almost a month, and everyone is left curious. They wonder where it came from, and since no one knows, they start speculating and applying their own meaning to it; for example, the narrator attributes the balloon to the time he met his lover underneath it, when she’s returned after a long absence. Ultimately, the balloon is significant because it has no meaning . . . it means whatever it needs to mean to the viewer. It’s such a weird, simple story that’s impressive, wonderful, frustrating, and layered.

-

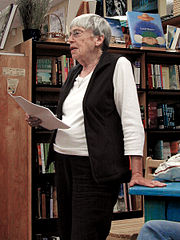

Author Ursula K. Le Guin

“The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas” by Ursula K. Le Guin: Yet another short story that’s barely a story at all—more like a fictional essay. Omelas is a perfect Utopian town. Its citizens are happy and there is no fear or pain. The narrator describes the glory of the town and consistently asks the reader whether or not they believe such a town is even possible, until she describes one final fact: somewhere in the town is a child, locked away in a room, malnourished and constantly suffering—a scapegoat. Everyone sees this child and understands that it pays the price for their Utopia. There are those who accept the child’s suffering for the town’s ability to thrive, and then there are those who walk away from Omelas, refusing to pay such a price for paradise. It’s a thought-provoking, ethically-twisted story and worth everyone’s time.

-

Author Jhumpa Lahiri

“Sexy” by Jhumpa Lahiri: “Sexy” might be the plainest story on this list—it doesn’t feel like high art or challenging literature, but it’s praiseworthy nonetheless. Miranda is in a relationship with a married Indian man, who once calls her “sexy” . . . the first time she’s ever been called that. The next time she hears the word, it sounds hollow, like it doesn’t mean anything, and she starts to question if her relationship means something, or if it is worth having at all. From a lesser writer, the actions of the story would come off as melodramatic—from Lahiri, the action is poignant and moving, and every word feels like it’s affecting the entire world.

If you can find these stories online, DO IT. Even if you only pick one, any of these are worth reading—some because they’re scary, some because they’re beautiful, all because they’re incredible. And if there’s a list of “50 Short Stories to Read Before You Die” out there, these are either on it, or should be.

Thanks for coming to class! See you next time.

Prof. Jeffrey

Recent Comments