Welcome back class.

Welcome back class.

I haven’t read a lot of Ernest Hemingway’s work—he is well-known for novels like For Whom the Bell Tolls and The Old Man and the Sea, both of which I haven’t read yet. I have read several of his short stories and only one of his novels: The Sun Also Rises. So when I saw Hemingway’s name on the 50-books list, I wasn’t surprised. But when I saw the book of his that was chosen—his short story collection Men Without Women—I was baffled, because I’d never heard of it before.

I typically refer to Hemingway as an author I don’t like, though I can understand why his works are studied and praised. But if I’m honest, Hemingway intimidates me like no other author. His stories are deceptively plain, and a fast reader will breeze past all of the subtleties of his work in search of the story. On the surface, his stories are almost boring; but in the smallest of details he hides the things that make his stories great. This can make a novel like The Sun Also Rises exhausting, because if you read too quickly, you can fly through the whole book having learned nothing at all. But in a four-page short story, once you reach the end and wonder exactly what happened, you have more of an opportunity to go back to the beginning and find what you missed—the small detail that changed everything.

That’s what I discovered with Men Without Women, and I enjoyed reading it much more than I thought I would. I won’t say it was my favorite read, or even close, but I earned something out of it. That’s more than I could have hoped for.

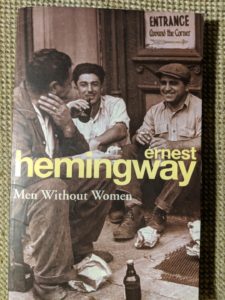

Charles McGraw and William Conrad in a 1946 adaptation of Hemingway’s story “The Killers”

It’s much harder to review a collection of short stories, because there are no broad strokes. Some stories stand out compared to others—“Ten Indians”, the story of a boy’s first heartbreak, is one I’d read before in high school, and things jumped out at me much more this time than 6 years ago. I’ve noticed the story “The Killers” has been turned into a movie several times, and I know why—the story is about two men taking hostages in a restaurant waiting to kill a man on arrival, and so many details are left out that it’s only natural for a variety of filmmakers to fill in the gaps.

Most of the stories are under ten pages, but two of the stories are closer to 30 pages: “The Undefeated,” which opens the book, is a story about an aging bullfighter proving his worth in a new era of the sport; and “Fifty Grand,” taking up the exact middle of the book, is the story of a boxer who fixes his own match to get a payout. I think both of these stories function as a foundation for the other stories—Hemingway’s method of building an interconnecting structure between stories that are otherwise isolated.

Two stories are hardly stories at all, which fits right in with the modernist writings of the era. “Today is Friday” is a script, following a group of Roman soldiers on Good Friday after Jesus is executed, and the cherry on top is that these soldiers speak in colloquial, Hemingway English. Then there’s “Banal Story,” which is either a nonfiction piece or a stream-of-consciousness experiment that lays out storytelling rules and then breaks them, and it ends by throwing in a cameo appearance from the protagonist of “The Undefeated,” dying in a hospital after his bullfighting days are over.

Author Ernest Hemingway

No one story is my favorite, nor would I call any the most shocking or most powerful. Hemingway’s balance as a writer is strong, and from that balance comes the common theme: even though there are technically women in several stories, each story focuses on men separately from women, or Hemingway’s trademark obsession with masculinity.

Hemingway’s stories are about athletes and soldiers (in a time before it was common for women to be either); his stories are about husbands and bachelors, and about boys becoming men; his stories are maybe even about sexuality and its unspeakable deviations; and more than anything, his stories are about how internally, men rarely if ever admit to themselves that there’s something going on under the surface of their stoic, frozen masculinity. Hemingway finds clever and creative ways for his stories to celebrate the masculinity he upheld until his dying day, while also subverting it in the details of those stories, and through that lens, it’s no wonder that Hemingway made the list.

And that explains, too, how Men Without Women made the list over his novels. Hemingway’s novels might have gained more popularity than his short stories over the years, but they are no less masterpieces. What better way to capture Hemingway’s perfect understanding of men, internally, culturally, and broadly, than to include a collection of stories diverse enough to do what a novel can’t?

So even though it had its faults, and it certainly isn’t my favorite, Men Without Women has left a mark where I didn’t imagine it could. Masculinity is not the kind of content I want to focus on; we live in an age of toxic masculinity, where culturally, men are often deservedly—I’ll say it again, DESERVEDLY—the bad guy. Hemingway seems to have known all the sides of masculinity, toxicity included, but he praised it’s healthy parts as well and took masculinity as the social force it is, warts and all. The result is a collection of good stories that I recommend.

There is one other thing I picked up from Hemingway about writing, and it’s one of my favorite metaphors. A good story will act like an iceberg—icebergs hide a silent majority of their mass under water, and less than half of its mass is all that can be seen. A good story shows only a small portion of its content—the rest is hidden under the surface, and though you can’t always see it, the rest of the story is absolutely hiding there, waiting to be discovered.

Next up is Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, just as much a masculinity-infused novel. And just like Hemingway, I have my problems with it, but it’s so well written I can forgive what I don’t like. It’s hard to pull off such an epic story in a mental ward, and Kesey manages just fine.

But more on that next time,

Prof. Jeffrey

0 Comments

1 Pingback