Good morning, class.

Good morning, class.

I’m not hiding my bias here . . . this is one of my favorite novels ever. I’ve read all 700 rambling pages of James Joyce’s Ulysses twice—once with the reassurance of a college classroom, and a second time “for fun.” I’ve mentioned it in almost half of the 100+ posts I’ve written for this blog (I recommend revisiting two of them: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Modern Literature; the review might help).

But I’m in the minority here. Most people who try Ulysses find it meandering and over-complicated. Even those that do like it tend to appreciate it from a distance, for how it changed history or defined a literary movement, but they don’t like to read it. I’m in the minority because I like experiencing the scope of the story, the empathy created by the characters, the literary connections, the “everything-is-connected”-ness of the details . . . I like it for exactly what it is, and not many people would say the same.

But, students, if I can show you why it made the 50-books list at all, maybe you can see why I like Ulysses so much.

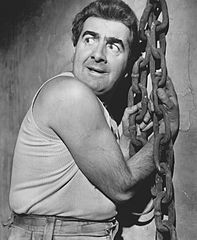

Actor Milo O’Shea as Leopold Bloom in the movie version of “Ulysses” (1967)

The story takes place in Dublin, Ireland, over the course of one day: Thursday, June 16, 1904. Leopold Bloom, our “hero,” is a Jewish advertising agent roaming the streets of Dublin, and his internal monologue narrates the story in messy fragments. His thoughts wander over (among other things) the child he lost 11 years ago, his father’s suicide, and the affair that his wife, Molly, is currently having with another man.

Meanwhile, Stephen Dedalus (protagonist of the prequel, Portrait of the Artist) deals with his mother’s recent passing, his unbearable alcoholic father, and his cynical disdain for just about EVERYTHING (he’s a little nauseating). He roams Dublin’s streets as well, and he and Bloom spend most of the day almost meeting, until they run into each other in the last few chapters like destiny—a father longing for a missing son, and a son wishing for a better father.

James Joyce, author of Ulysses (1922)

And then, without giving too much away, the novel ends by giving Molly Bloom a voice of her own—the final chapter is her epic monologue reaching beyond the confines of the single day. She rambles through cataclysmic run-on sentences on sex, love, marriage, memory, and femininity, and fondly remembers the day when she agreed to marry Leopold.

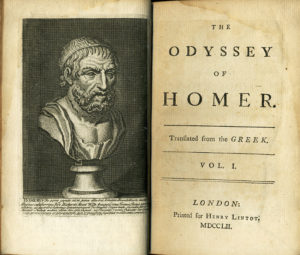

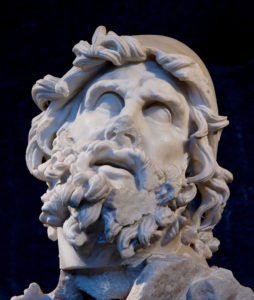

There are too many literary references to count, but the most important ones are about The Odyssey by Homer. Bloom is Odysseus, journeying from his home and back (boiling down 20 years into one day), trying to return to his “son” (Stephen/Telemachus) and his wife (Molly/Penelope). The terrifying Cyclops becomes the bigot spouting his beliefs in the bar, while the visit to the underworld becomes a funeral, and the entrancing witch Circe takes the form of a prostitute in a brothel.

These Odyssey references, where the name Ulysses comes from, give the novel it’s epic-ness. The length of this one day is impressive, so filled with detail that it overflows at the seams, and it still doesn’t capture every single moment of the day. The ancient has been updated to match advances in technology and societal evolution, but it still meets the same archetypes it’s known for.

These Odyssey references, where the name Ulysses comes from, give the novel it’s epic-ness. The length of this one day is impressive, so filled with detail that it overflows at the seams, and it still doesn’t capture every single moment of the day. The ancient has been updated to match advances in technology and societal evolution, but it still meets the same archetypes it’s known for.

Most importantly, Bloom is a modern Odysseus—less a warrior, more a gentle soul. He is kind to animals, has a love for science, and empathizes with Molly’s extramarital desires. Unlike most men, he knows he doesn’t own her, and that she could be suffering just as much as he is over their long-lost child. He leaves only room in his heart for compassion, making him more of a hero than anyone else in the story . . . because a modern hero isn’t someone physically strong, but rather someone who performs simple acts of kindness.

Statue of James Joyce in Dublin, Ireland

So, even though there are literary reasons why Ulysses is a masterpiece, it’s Bloom’s compassion and empathy, found throughout the novel, that make this book good. It may be hard to see under the complicated language and plot, but this novel has more love on any one page than most novels can show in a hundred. Joyce handles grief, prejudice, hope, sex, depression, death, longing, wonder, and life, all with a deep and profound love.

Sometimes, it surprises me how I’m in the minority in liking this book, and then I flip through its pages and remember—this novel is HARD to read. It’s an experience that nothing can replace, and for that reason it belongs on the list, but it is not a book you just pick up and read!

If you are going to try it, and you don’t have a literary professional standing nearby at all times, you might try reading a guidebook along with it—I recommend Ulysses and Us: The Art of Everyday Living by Declan Kiberd. It’s pretty focused on understanding the intentions behind the novel, and it helped me find the love within Ulysses. I also recommend any and all online resources—a summary won’t replace the novel, but it will help you understand what on earth is happening.

If you are going to try it, and you don’t have a literary professional standing nearby at all times, you might try reading a guidebook along with it—I recommend Ulysses and Us: The Art of Everyday Living by Declan Kiberd. It’s pretty focused on understanding the intentions behind the novel, and it helped me find the love within Ulysses. I also recommend any and all online resources—a summary won’t replace the novel, but it will help you understand what on earth is happening.

I may be a 23-year old blogger, but I think I understand Ulysses, so feel free to ask me questions after class (a.k.a. in the comments below). I absolutely didn’t cover everything here, but I’ve got plenty more to say on this subject if you want to know more. Seriously, ask me questions—all I want to do is talk about Ulysses all day.

Now that I’ve finished Ulysses, I’ve started reading Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë. Whenever I tell people this, they stare, like reading Ulysses and Jane Eyre outside of school isn’t normal behavior. It seems perfectly normal to me.

Anyway, I’ll see you for class next week.

Prof. Jeffrey

Recent Comments