Welcome back, class.

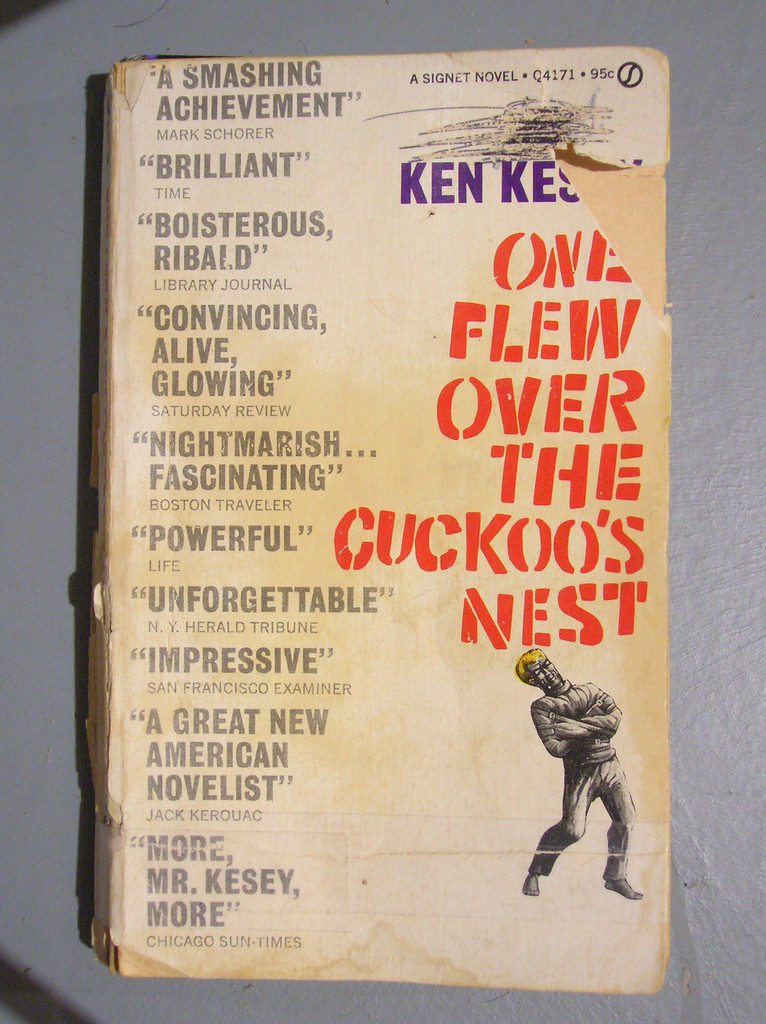

From the start, I was comparing Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest with Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar. Both focus on characters with mental illness, as well as the concept of mental illness, while tackling loosely related problems like American culture, sexism, and the conflict between the individual and society. But that’s it. Beyond that, the books are as different as The Diary of Anne Frank and the Harry Potter Series.

And what makes them so different? Kesey’s novel is only about mental illness on the surface. There are clearly characters who are mentally ill, including the narrator, but that illness is simply the backdrop for a larger story—a story about oppression, anarchy, identity, and society. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest isn’t about curing those who are ill, but about freeing those who are enslaved. There are issues with that approach, but the story is good enough to rise above those issues.

First of all, the writing is SOLID. Everything about Kesey’s style is original, enjoyable, clever . . . it’s audible and graphic and is meant to immerse you into the vivid and uncomfortable world of a mental ward. On this ward, tragedy and terror happen without warning, and the smallest of details cause the biggest impact—the writing reflects that, and the few peaceful scenes that occur take such sharp turns into chaos that, after a while, the reader realizes there aren’t any peaceful scenes at all . . . only anarchy and the build-up to it. The genius of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is in Kesey’s portrayal of the story’s events, and if there’s only one reason it made the list, look no further. Knowing full well I can’t do his amazing style justice, I encourage you to read it yourself and see what I mean.

First of all, the writing is SOLID. Everything about Kesey’s style is original, enjoyable, clever . . . it’s audible and graphic and is meant to immerse you into the vivid and uncomfortable world of a mental ward. On this ward, tragedy and terror happen without warning, and the smallest of details cause the biggest impact—the writing reflects that, and the few peaceful scenes that occur take such sharp turns into chaos that, after a while, the reader realizes there aren’t any peaceful scenes at all . . . only anarchy and the build-up to it. The genius of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is in Kesey’s portrayal of the story’s events, and if there’s only one reason it made the list, look no further. Knowing full well I can’t do his amazing style justice, I encourage you to read it yourself and see what I mean.

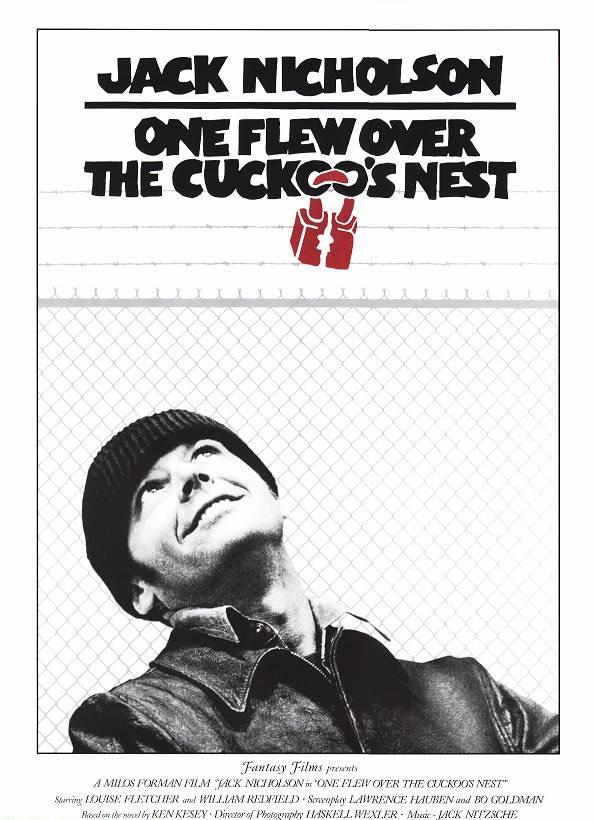

Then, there’s the story itself—Randle P. McMurphy is a criminal who pleads insanity in the courtroom, and winds up on the ward with the actual mentally ill. Within hours, he sees that the situation on the ward is a step above prison, but the countless restrictions make life about as flexible as concrete, and he decides that he won’t stand for it. The leader of the ward is Nurse Ratched, a domineering woman whose sole pleasure seems to be rigidity and order—every move she makes is to perfect the lives of her patients whether they want it or not. McMurphy and Ratched become fast enemies, and the rest of the patients get caught in the crossfire.

It’s easy to see McMurphy as the hero and Ratched as the villain, and while Ratched has next to no redeemable qualities, McMurphy is a far cry from a great leader or liberator in any scenario. His criminality alone isn’t a series of innocent slips—it’s implied he’s done some terrible things. He has moments of kindness, most of which are veiled maneuvers to try to get what he wants—more freedom on the ward for something trivial, or at least the ability to upset the power dynamic and throw Ratched off her game. But there are moments of rebellion on behalf of the other patients, and those moments make McMurphy more complicated and more interesting. Kesey refuses to let McMurphy fall into labels that trap him like “hero” or “anarchist” or “revolutionary.”

It’s easy to see McMurphy as the hero and Ratched as the villain, and while Ratched has next to no redeemable qualities, McMurphy is a far cry from a great leader or liberator in any scenario. His criminality alone isn’t a series of innocent slips—it’s implied he’s done some terrible things. He has moments of kindness, most of which are veiled maneuvers to try to get what he wants—more freedom on the ward for something trivial, or at least the ability to upset the power dynamic and throw Ratched off her game. But there are moments of rebellion on behalf of the other patients, and those moments make McMurphy more complicated and more interesting. Kesey refuses to let McMurphy fall into labels that trap him like “hero” or “anarchist” or “revolutionary.”

One of the flaws of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is its Hemingway-esque focus on masculinity—this is a novel about men and for men, with a sexualized woman as the villain. In this world, men are celebrated for things that are crass and inexcusable, disguised as rebellion against the established order. But, to be fair, in a world where the established order is a specific kind of oppressive—sexless, muted, inflexible—performing revolutionary acts that flaunt morality or social code may be inherently good. What bothers me is that these acts tend to be for men at the expense of women, and Kesey created a story that allows for that, knowing that to soften the backward-ness of these dynamic characters would be to weaken the story. The good and powerful themes of this novel come at that cost, so be willing to pay it when you pick it up.

Despite that backward-ness, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest has a violent wit and a very, VERY well-told story. It may be played for crazy at the expense of the mentally ill, but it’s a novel that presents the distinction between society and its marginalized individuals with force and flare. I encourage others to read it with eyes open for the good, the bad, and the ugly.

That’s FORTY BOOKS DONE. Only ten more to go! There are some books in this final round that I’ve already read, and some that I know absolutely nothing about, so we’re not going into unfamiliar territory but we are reaching the end of our journey. I feel more enlightened already.

Next up is The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, similarly controversial for very different reasons. I hope I can do it justice, because I’ve read this novel several times, and I’ve loved it and hated it, and even felt a high-school-indifference to it. We’ll see how it goes.

Until then,

Prof. Jeffrey

Overcoming the Monster (that’s, like, the millionth time I’ve mentioned this one—take the hint, it will be on the test)

Overcoming the Monster (that’s, like, the millionth time I’ve mentioned this one—take the hint, it will be on the test) A professor once told me that there are two ways to start a story—either a stranger comes to town, or someone decides to leave. Whatever happens from there changes everything. Somehow, that simple prompt is both challenging and comforting.

A professor once told me that there are two ways to start a story—either a stranger comes to town, or someone decides to leave. Whatever happens from there changes everything. Somehow, that simple prompt is both challenging and comforting.

Recent Comments