Dante’s depiction of Hell (portrait by Botticelli)

Happy New Year, class! Let’s jump right into some Italian literature.

Dante’s The Divine Comedy should not be on the list. My professional opinion is that no one has to read this book before they die. Your time could be better spent reading some of Dante’s famous quotes from the epic poem, looking at the maps of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven that Dante describes, and studying up on how The Divine Comedy affected everything written after it.

If you’re interested, by all means, read it! It’s a great story and it really has affected everything written after it—even on the list, it directly affected The Canterbury Tales, Ulysses, The Lord of the Rings, the His Dark Materials Trilogy, and everything in between. But it should be studied and analyzed in a college class. It’s not the kind of book you read in your spare time, and it’s not the kind of book that everyone has to read.

Before I come down too hard on Dante, why don’t I tell you what the poem is about—a journey through the afterlife as Dante himself tries to find his love, Beatrice. The ancient poet Virgil guides him through the nine circles of Hell, and then up the seven ledges of the mountain of Purgatory. Because Virgil can go no further, Dante meets Beatrice at the top of Purgatory (where the garden of Eden is, by the way) and together they ascend through the planetary spheres of the heavens. Dante meets figures from history every step of the way—the worst being punished eternally for their sins, and the best enjoying the fruits of Heaven. Meanwhile, Dante’s guides teach him as much as they can about the political sides of the afterlife, the spirituality that makes all three realms function, and the moral nature of things like love, hope, good, evil, faith, fate, and free will.

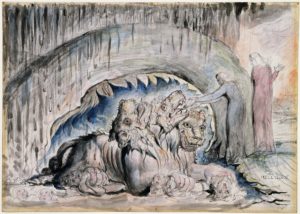

Satan portrayed as a three-headed beast in Dante’s Inferno

The things Dante imagined for The Divine Comedy are beyond belief—the terrifying three-headed Satan chewing on the greatest betrayers of human history, the Eagle composed of the souls of just rulers in the seventh sphere of Heaven, the Virgin Mary depicted as queen of the great Rose of the Blessed made of light in the Empyrean . . . it’s all a lot to take in. And right next to these fantastic images are passages about how love drives all human action to both good and evil, and why it’s reprehensible to pity those souls being punished for their crimes. The Divine Comedy is thought-provoking, emotional, and vivid, and it accomplished enough to alter literature, art, culture, and history permanently—clearly it had enough reason to make the list.

But for all the good and interesting moments, it’s incredibly difficult to read on it’s own. I used as many helpful guides as I could, and most of them made more sense than the poem itself. A smarter person might have even enjoyed reading it for fun, but I’m unfortunately not a part of that category. But maybe a person who’s read it before—studied it in a class, made themselves flashcards, answered essay questions . . . the whole nine yards—maybe that person could make sense of the reading, and could even reinterpret certain parts that didn’t click before, without bending over backwards like I did. Without help, The Divine Comedy is confusing and exhausting, so much so that I don’t believe it should have made the list.

Dante Alighieri

I recently learned this lesson with Ulysses, which I still love more than almost every novel on the list. But I studied it in a class that I loved with a professor I respected. If I had read for this blog for the first time, I would have thought it was a rambling mess. I would never have discovered the science and art of Joyce’s beautiful writing, and I never would have discovered the meanings behind it. But I had careful guidance alongside my frustrations, and that made all the difference. I imagine that reading Ulysses without help would have been more difficult than reading The Divine Comedy without help.

Works like that shouldn’t be on the list. These books need to be accessible—if not to the average person, at least to the average reader. The kinds of books everyone should read are the ones that can change a person’s life, round out their education, or give them a new perspective. The Divine Comedy did just about none of these for me because it was too far away from me, and I doubt it could do a bit of good for a person who isn’t in a college course on Italian literature.

Next up, I’m finishing up The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas. I wouldn’t put it in the inaccessible category like The Divine Comedy and Ulysses, but it wasn’t easy either. Having started this one over 3 months ago, it has been a journey reading this prison-break epic. But more on that next time!

Prof. Jeffrey

Recent Comments