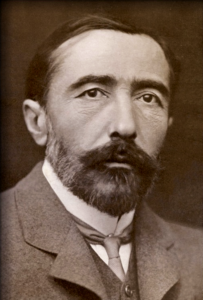

Author Joseph Conrad

Hello again class.

The Secret Agent by Joseph Conrad is something of an espionage thriller—it’s not James Bond, though. It’s more mundane than your average blockbuster hit. On the surface, anyway.

Before I started The Secret Agent, the professor assigning it hooked me by saying that Conrad’s novel predicted acts of terrorism like the 9/11 attack, almost one hundred years beforehand. That’s not exactly true—not in the way I expected. But the way the book follows a terrorist attack out of sequence (the suicide bombing of an observatory, linked to a group of radical anarchists) makes that fictional event thematically linked to the events of 9/11. The novel’s approach to radicalism, government, corruption, and ideology paints the portrait of an act of terrorism in a modern world. That’s a world we’re familiar with now—not only because of 9/11, but because of the normalcy of violence done by terrorists with easy-to-buy weapons and misguided ideologies. Conrad didn’t predict 9/11 itself, but he predicted the world in which it happened.

The Secret Agent takes place in the late 1800’s (right before the era of modernism in literature began to pick up speed). In it, we follow the agent Adolf Verloc, stationed in London on behalf of a foreign government. He owns a pornographic shop and lives with his wife and her family, and on the side he participates in an illegal anarchist group and reports back to his own government on their actions.

Just as we start to understand this setup, the novel jumps forward and backward in time. A set of characters begin solving the mystery behind the bombing at the observatory, marveling at the horror and “beauty” of it each in their own way. Then we go back to solve the mystery ourselves, and the twist is surprising enough for a novel like this, especially of it’s time.

Part of what makes The Secret Agent special is it’s treatment of time. The movement back and forth outside of chronology was not a standard like it is in today’s film and TV—it was an experimental way to tell this story to its greatest benefit, not done for thrills (not only for thrills, at least). The same thing happens when Conrad’s characters focus on the nature of the explosion, and the people who experienced it—the moment it happened must have lasted an eternity, while the eternity of life breezes by in a moment. Conrad’s point seems to be that time isn’t as stable a structure as we like to imagine—time is in flux, and our misguided perceptions of time only widen the discrepancies between perception and reality.

The characters of The Secret Agent are trapped in this revolving plot, fated to the doom of this explosion and its aftermath. There’s a sense that the explosion is relived when we jump back in time, and the memory of it helps us to do that. In that way, it’s related to the 9/11 attacks. While those directly affected by it suffered so much more, we all deal with a kind of global trauma from that day. Through our memories of the event we relive the experience, and those moments get played out again as if for an eternity. One second is not equal to another—the handful of seconds on that day, when billions of lives changed, had more of a cost than most of the insignificant seconds that make up the day-to-day.

What really makes the novel work is Conrad’s writing, which is difficult and beautiful. His total understanding of his characters and the political action they take are matched by his style. That style may not be for everyone, but for those willing to put in the time and effort, it’s incredibly rewarding. That same style earned Conrad plenty of acclaim with his novel Heart of Darkness, and we’ll go into more detail when that blog post comes along.

As for The Secret Agent . . . while it sounds like it’s inclined to glorify terrorism, I can assure you it doesn’t. The Secret Agent has lasted so long because it shows terrorism for what it is: misguided violence with unbelievable consequences, even beyond the lives lost. Conrad uses ideas like this to criticize radical thinking as well as government inefficiency, both of which our world still suffers from as much as acts of terrorism. It’s worth reading because of its continued relevancy, and that’s why it should have made the list.

I’m still working through Gulliver’s Travels again, and it’s special in its own way. If I had to choose, something like The Secret Agent would be on the list instead of Gulliver’s Travels, but I know which one has affected the world of literature more. The Secret Agent has had little impact beyond it’s own area of literature, but Gulliver’s Travels has a uniqueness that has affected everything after it. More on that next time.

Prof. Jeffrey

Recent Comments