Good morning class.

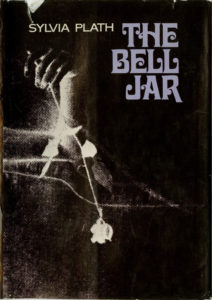

If The Bell Jar is any indication as to what Sylvia Plath’s life was like, she was surrounded by tragedy. She wasn’t a typical tortured artist, if there is such a thing—I imagine that her art would have thrived fantastically without her mental illness. As it is, I believe her art thrived in spite of her troubled mind, not because of it. Even in my own limited experience with mental illness, I’ve never seen psychological turmoil as a gateway to impactful creativity . . . I only see it as a hindrance.

That might be reason enough to read The Bell Jar, which subverts misconceptions about mental illness, women, and the American dream without hesitation. Plath holds nothing back, and it’s painful, powerful reading.

The story follows Esther Greenwood, a young woman with a bright future who begins to suffer from depression. At first it’s mild—inconvenient distresses that affect her life here and there—but it develops into suicidal thoughts and actions. One almost-forgettable moment stands out to me: she sleeps in one morning, innocently enough, because she feels like there’s nothing to look forward to if she gets up. The light from the window shines in, but she buries herself in her sheets and under her pillow, back into the darkness. It’s subtle, but it’s a clear sign of her illness affecting her every moment.

The story follows Esther Greenwood, a young woman with a bright future who begins to suffer from depression. At first it’s mild—inconvenient distresses that affect her life here and there—but it develops into suicidal thoughts and actions. One almost-forgettable moment stands out to me: she sleeps in one morning, innocently enough, because she feels like there’s nothing to look forward to if she gets up. The light from the window shines in, but she buries herself in her sheets and under her pillow, back into the darkness. It’s subtle, but it’s a clear sign of her illness affecting her every moment.

After a suicide attempt, Esther is committed to an institution, where she goes through medication and shock therapy. She describes her condition as being trapped under a bell jar, breathing in the same toxic air every moment of every day, no matter where she is or who she’s with—the bell jar is always there.

The extra layer of her struggle is being a woman in 1950’s America. She goes on dates with men of differing levels of ingrained misogyny. She sees other women around her as reflections of her two extreme options—the perfect do-good lady and the rule-breaker—and only she seems to belong in between. Several people, including her mother, pressure her towards finding a man, settling down, beginning a family . . . and everyone cautions her against sex before marriage, despite the obvious double standard. Esther’s life seems to be one hardship after another, and the 1950’s do her no favors.

Author Sylvia Plath

The Bell Jar is not light reading. Several times, over multiple chapters, Esther does more than consider suicide in a passing thought. She analyzes the best way to kill herself, and goes through the motions before being interrupted or facing an insurmountable obstacle. At one point, she remarks that her body has “little tricks” that keep her from killing herself, like an internal instinct she has no say over—but if she had the whole say, she’d be dead already. When she actually conquers this instinct, the suicide attempt portrayed on the page is simple and disturbing.

But as graphic as The Bell Jar can be, that’s not the reason to read it—the reason to read it is because of what Plath gets right in the details. The subtleties of depression are portrayed with honesty, and with no grand presentation. To read The Bell Jar is to get a nuanced depiction of a troubled mind.

Next up, I’m reading The Diary of Anne Frank—similarly not-light reading. But I’m excited because I know that it’s no portrayal; her diary, her actual thoughts, convey her life as a young woman in a strange kind of captivity. Her diary did as much for understanding young women as The Bell Jar did, if not more. It’s also not a graphic portrayal of a tragedy; it’s the ups and downs of her life, come as they may, and it’s even more honest than The Bell Jar could hope to be.

But more on that next time.

Prof. Jeffrey

Recent Comments