Good morning class.

Good morning class.

The 50-books list has a handful of options marketed for children: i.e., Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and the Harry Potter series. But I think it’s strange that there isn’t a single entry on the list by Dr. Seuss—a man whose work is synonymous with children’s literature.

Dr. Seuss’ picture books cover a wide range of topics marketed for all ages. In his quirky, made-up-rhymes, overused-exclamation-points way, he tackles environmentalism, prejudice, and politics alongside boredom, bullying, and loneliness, and it’s never dull. So I officially declare that at least one of Dr. Seuss’ works should be one of the 50 books you read before you die.

I’m too weak to claim one is better than the rest, so I chose my top 5!

1. Horton Hears a Who!

Statue of Thodor Seuss Geisel and his “Cat in the Hat” character.

Symbolically, the politics in this story are about involvement vs. isolationism—what happens when those with power intervene to help those without. Written in the 1950’s, this could easily be about WWII or the American-Korean conflict, criticizing Americans who wanted to stay out of international issues. Dr. Seuss rarely shied away from such controversial topics, even when writing for kids.

But even if that was Dr. Seuss’ intention, the messages for kids are more wholesome: all people are equal, even if they don’t have the power to say so; stick to your true beliefs, even if others make fun of you or hurt you for them; and every voice counts in times of trouble, so don’t be afraid to stand with others. This book is inspiring, and an emotional rollercoaster. Of course there’s a happy ending, but that doesn’t make it less stressful when the town of Whoville is moments away from being destroyed toward the end—I get chills reading it every time.

2. How the Grinch Stole Christmas!

I think it’s a stroke of genius from Dr. Seuss that the Grinch hates Christmas simply for the sake of hating Christmas. He hates the noise and the feasting and the singing—there’s no explanation, just that he hates it from the bottom of his too-small heart. It makes him instantly unlikable and easy to transform by the end.

I think it’s a stroke of genius from Dr. Seuss that the Grinch hates Christmas simply for the sake of hating Christmas. He hates the noise and the feasting and the singing—there’s no explanation, just that he hates it from the bottom of his too-small heart. It makes him instantly unlikable and easy to transform by the end.

And by the end, the message is clear—Christmas is more than decorations and gifts. Dr. Seuss doesn’t say what Christmas is beyond that, because that’s enough. Christmas may look flashy and bright, but what it actually is—the love and joy and peace-on-Earth that it stands for—is beyond words. Not many Christmas stories can relay that message well, and this is one of the few.

3. The Lorax

I tend to forget that “The Lorax” has a happy ending, because the death and decay caused by the greedy Once-ler’s business fills up so much of the story, and packs such a powerful punch, that the end just can’t match. Watching the bright and colorful land of the Lorax darken page by page, and seeing the devastating results of a rampaging business, has stuck with me more than the final scene, where the remorseful Once-ler passes a final Truffula seed to a stranger, who may be able to bring the forest back.

The environmental message is painful and foreboding (particularly, the whack of the final tree cut down and the Lorax’s final trace in his land, the word “UNLESS,” are both emotional battering rams). It’s a sad story, even with the happy ending, and most writers wouldn’t dare write such a story targeted at children—though the message probably means more to adults anyway, as they read this story to their children, their eyes forced open to the injustice toward the Earth. Because of this, I think “The Lorax” says more about Dr. Seuss than most of his books.

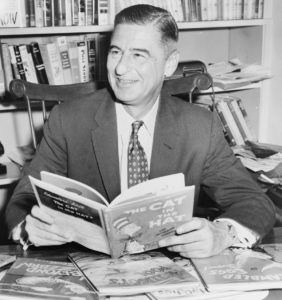

Author and Illustrator Theodor Seuss Geisel

4. The Sneetches

This is one of Dr. Seuss’s underrated masterpieces—I’ve only met a handful of people that recognize it. But I grew up with “The Sneetches,” and it’s themes of prejudice, greed, and classism are with me to this day.

The Sneetches are a divided people, the privileged identified by stars on their bellies, and the rest with no “stars upon thars.” Then along comes Sylvester McMonkey McBean with his star-adding machine, which can put stars on the Sneetches bellies and give them the world they could never have—all for three dollars each. But then, all the Sneetches are equal, which doesn’t sit well with the Sneetches born with their stars. So they go through McBean’s star-off machine, upsetting the rest of the Sneetches . . . well, chaos ensues.

The Sneetches learn their lesson, of course—a Sneetch is a Sneetch, star or no. It’s one of those lessons that people are still working on, and the Sneetches are a good model to study.

5. Oh, the Places You’ll Go!

In a previous post, I talked about this book as particularly special to me—like all of Dr. Seuss’ books, it has a way of speaking to the soul. It doesn’t have a big story or political message, but it’s full of hope and inspiration. Dr. Seuss tells the reader directly what they will face, both the good and the bad, as they grow up and move out into the wide weird world.

In a previous post, I talked about this book as particularly special to me—like all of Dr. Seuss’ books, it has a way of speaking to the soul. It doesn’t have a big story or political message, but it’s full of hope and inspiration. Dr. Seuss tells the reader directly what they will face, both the good and the bad, as they grow up and move out into the wide weird world.

“Oh, the Places You’ll Go” doesn’t shy away from the pain, fear, and loneliness the world can cause (even if it’s in Dr. Seuss’ quirky way, it still means a lot). Coupled with the determination, success, and wonder the reader will meet, the good and the bad balance each other out, and make the message more meaningful. But it scales back at the end—the glamour and glory of all these possible new places boils down to an almost-blank page, leaving it to the reader to imagine what’s next. It’s a very hopeful message.

Even with these 5 favorites, I still feel like I’m missing several of Dr. Seuss’ greatest works—I probably forgot a few. Tell me your favorite Dr. Seuss picture book in the comments!

Next week, I’ll be writing about The Great Gatsby, so be prepared to discuss. It’s probably the easiest and most comfortable literature I’ve ever read, but it’s also one of the most layered and complex stories I’ve ever come across. But more on that next time.

Have a good week!

Prof. Jeffrey

Recent Comments