Happy New Year, class!

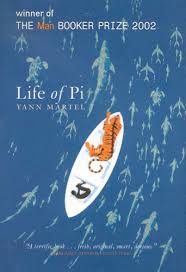

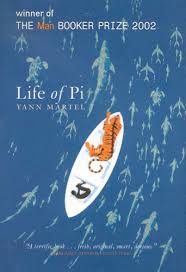

Yann Martel’s Life of Pi is one of the strangest books I’ve ever read. It tells the story of a teenage Indian boy named Pi, who is trapped on a lifeboat in the Pacific with a small group of animals, including an adult Bengal tiger. This is his story of survival—he is forced to train the tiger, using his father’s zookeeper knowledge, while also surviving isolation, hunger, infection, and the terrors of the open ocean. If this was all it was, it would still be a unique and remarkable story…but of course, there’s more to it.

Yann Martel, author of Life of Pi

The author’s note claims that this is “a story that will make you believe in God.” It’s a tall order, and I think Martel accomplishes this—his philosophy is that belief comes down to the story people choose, which is as important as the facts themselves.

He makes this happen through Pi, an amazingly original character. This is a boy who fell in love with religion at first sight; he compares his own obsession with God and faith to his older brother’s obsession with sports and music. He was raised Hindu from his mother, while his father shunned religion politely; he eventually found Christianity and Islam as well, and actively practiced an interfaith religion for all of his life.

Clip from the movie adaptation of Life of Pi

What Pi loves most about religion are the stories. The overflowing number of gods and deities in Hinduism, the overarching prologue and tale of Jesus as Christ, the beautiful imagery and faith of Islam…these keep him going throughout his struggles. More importantly, his faith is the heart of the story. Pi is so overflowing with love, with worship and belief, that it pours off of the pages. His journey with belief has more of an impact on his life than his ordeal on the Pacific.

That being said, Pi’s ordeal is terrifying, graphic, and even hilarious at times. The tiger—named Richard Parker, in a strange origin story—is as much a character as Pi, and their journey toward communicating with each other is a roller coaster. Richard Parker can never be trusted, and though there are moments that indicate he is more than an animal, Pi is constantly reminded of Richard Parker’s natural instincts. Any moment of weakness from Pi could mean death…for both of them.

That being said, Pi’s ordeal is terrifying, graphic, and even hilarious at times. The tiger—named Richard Parker, in a strange origin story—is as much a character as Pi, and their journey toward communicating with each other is a roller coaster. Richard Parker can never be trusted, and though there are moments that indicate he is more than an animal, Pi is constantly reminded of Richard Parker’s natural instincts. Any moment of weakness from Pi could mean death…for both of them.

Hidden in this captivating plot is that common English class theme, “man vs. nature.” Richard Parker is a force of nature, and Pi has to learn that over and over again—that Richard Parker is not his friend and cannot understand love. Martel’s point with this distinction is the same point he makes about religion and belief toward the stories we choose. Human beings have the capacity to understand religion, to love, to wish for order out of chaos. Animals have only their instincts—no faith, no order, no love.

Clip from the movie adaptation of Life of Pi

It’s not a popular distinction—no one wants to think their dog or cat doesn’t love them. Pets understand dependency, fear, want, and certainly happiness, but not something as complex as love. That’s why we take them and care for them as pets, and why we place them in the safety of zoos and do what we think is best for them. The responsibility of caring for animals is, morally speaking (and religiously speaking, in a way), a human obligation. To understand this is to sense the overwhelming spectrum of emotions this novel provides.

I love this book. It means so much to me. It is original, inspiring, and powerful. I can’t capture it all in a blog post, so I recommend reading it. Yann Martel is an amazing author, and he has created an amazing work of fiction.

Up next, I’m currently reading and finishing The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer. I’m not really enjoying it yet…it has it’s moments, sure, but can be a bit much. We’ll see what happens. Thanks for coming to class, and again, happy New Year!

Prof. Jeffrey

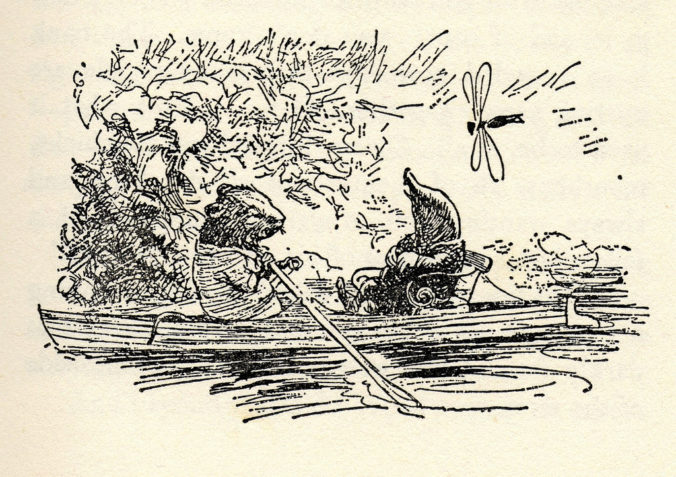

The Wind in the Willows is one of the most pleasant stories I’ve read in a long time. It’s short and entertaining, full of talking animals on crazy adventures, and never shallow enough to lose suspension of disbelief. More importantly, it’s a children’s story—easily what a parent would read to their children every night, which means unlike most novels on the 50-books list, this actually is something everyone should (and could) read.

The Wind in the Willows is one of the most pleasant stories I’ve read in a long time. It’s short and entertaining, full of talking animals on crazy adventures, and never shallow enough to lose suspension of disbelief. More importantly, it’s a children’s story—easily what a parent would read to their children every night, which means unlike most novels on the 50-books list, this actually is something everyone should (and could) read.

I do still question it’s inclusion on the list. The excellent writing and the portrayal of a child’s fantasy dreamworld is already on the list—

I do still question it’s inclusion on the list. The excellent writing and the portrayal of a child’s fantasy dreamworld is already on the list—

That being said, Pi’s ordeal is terrifying, graphic, and even hilarious at times. The tiger—named Richard Parker, in a strange origin story—is as much a character as Pi, and their journey toward communicating with each other is a roller coaster. Richard Parker can never be trusted, and though there are moments that indicate he is more than an animal, Pi is constantly reminded of Richard Parker’s natural instincts. Any moment of weakness from Pi could mean death…for both of them.

That being said, Pi’s ordeal is terrifying, graphic, and even hilarious at times. The tiger—named Richard Parker, in a strange origin story—is as much a character as Pi, and their journey toward communicating with each other is a roller coaster. Richard Parker can never be trusted, and though there are moments that indicate he is more than an animal, Pi is constantly reminded of Richard Parker’s natural instincts. Any moment of weakness from Pi could mean death…for both of them.

Recent Comments