Happy holidays, class!

As I’ve said before, our class textbook is flawed. There’s certainly more than just 50 books to read before you die—what about the books that didn’t make the cut? Not to worry…Prof. Jeffrey to the rescue.

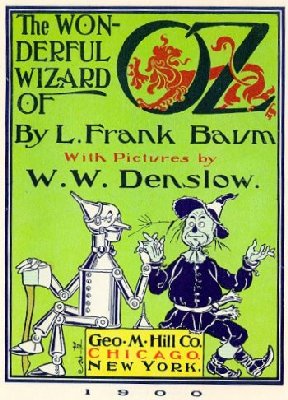

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is one of those books. I can guess a couple of reasons why it didn’t make the list: it can come off as disjointed or unstructured, and it isn’t as strong as other fairy tale narratives, such as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (I do keep coming back to that one, don’t I?). Nonetheless, it’s worth reading.

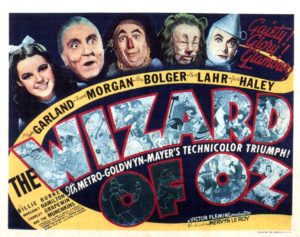

The Wizard of Oz (1939)

In many ways, the novel has been surpassed by The Wizard of Oz (1939), considered one of the greatest films of all time. From there, the story has spawned many revisionist versions, such as Gregory MaGuire’s The Wicked Years series or the use of the characters on TV shows like NBC’s upcoming show Emerald City or ABC’s Once Upon a Time. The movie musical has also inspired musical adaptations such as The Wiz and Wicked. The cultural impact may be more important than the original story.

Even so, L. Frank Baum’s novel on its own has made milestones. It’s essentially the first “American” fairy tale—a children’s story built on the backbone of late 19th century American culture. References to the farming population of the Midwest, the Industrial Revolution, the glamour of urban life, and the overwhelming sense of social, economic, and political influences are seen through the eyes of Dorothy Gale, an innocent girl in the middle of it all. It isn’t a stretch to call Oz the American Wonderland—just as amazing to behold, and just as terrifying in the eyes of a child.

Wicked (1995), novel by Gregory MaGuire

It’s enough of a remarkable story to keep returning to, over and over again. Remakes, revisions, rewrites…everyone has an image of Oz they prefer, and it’s diverse enough to withstand new adaptations. Talking animals, wicked witches, wonder and adventure and terror—it’s got everything a good fairy tale needs. Even if you’ve seen the movie and you know the story, the original is worth the read.

Your homework: what other books belong on the list? What books do you think people should read before they die? Put it in the comments!

I’ll be finishing Life of Pi next. See you next week.

Prof. Jeffrey

Recent Comments