Hello again, class.

Hello again, class.

The first thing you notice about Anna Karenina is how long it is. Hopefully, the second thing you notice is how short the chapters are—all of them, two or three pages a pop. It’s really easy to read a chapter a day, and most chapters pick up in the exact spot where you left off last—that’s why, for the past 15 books I’ve written about for this blog, I’ve been reading Anna Karenina on the side. It’s hardly made a dent in my time, even though it took several months to read.

I’ve heard that Anna Karenina is the best novel ever written. Though my vote for that spot is still Ulysses, I can see why Tolstoy’s novel is preferable—Anna Karenina uses a large cast of characters and their diverse inner thoughts to tell the kind of story you can’t look away from, where passion leads to terrible decisions and societal systems punish everyone, without regard to right or wrong. For that, Anna Karenina makes the list of books to read before you die.

Actress Greta Garbo as Anna in one of the several movie adaptations of Anna Karenina.

The novel follows two major stories that intersect and branch out from each other. One story is focused on Anna, a married woman who falls in love with another man and begins an affair, setting in motion the events of the novel. The other story focuses on the landowner Konstantin Levin and his relationship and eventual marriage with the noble Katerina (Kitty). It’s almost like reading two different novels, except for the moments when one story affects the other.

In Anna’s story, her life falls apart almost immediately—once she meets Alexis Vronsky, the man who becomes her lover, her marriage collapses like wet paper. Her attachments to her extended family, her love for her son, her standing in Russian society . . . all are kindling for the fire that consumes her life. Levin’s story is more traditional—he pines for Kitty, learns to live without her, happily regains his relationship with her, and, once married to her, begins the life expected of a husband. But the subtleties of his story reveal contradictions ingrained in marital expectations.

If the entire novel could be boiled down into one thought, that’s it: Anna Karenina is about the flaws of marriage, and in other systems that society puts so much importance on. More than anything, Tolstoy seems determined to point out how complicated and convoluted the ideas and expectations of marriage are, and to condemn it as part of the problem.

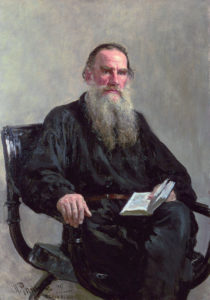

Author Leo Tolstoy

The novel is praised for realism, but be warned: I don’t mean present day realism, I mean 1800’s realism (which means that Tolstoy doesn’t linger on the gory details, but they’re still there). Anna Karenina has that same quality that Modernism abides by—the need to break down traditions and widely held values for the sake of shifty truths. Tolstoy does this in a way that shows off every character and their uniquely flawed perspectives, warts and all. No one character has a complete picture of the events, so it’s up to the reader to decide what the truth is, despite any one character’s beliefs or morals.

Tolstoy’s determination makes Anna Karenina challenging and important. It doesn’t hold back anything—that’s the kind of realism it brands itself with, which works to the novel’s credit.

Next up, The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath. Of what I’ve read so far, there could be several comparisons between the protagonist Esther and Tolstoy’s Anna—I can’t share more detail without spoiling either novel, but suffice it to say that mental illness in women is misrepresented in most literature, and that what Tolstoy didn’t get right in Anna Karenina is sure to be corrected by Plath’s personal experience. I don’t look forward to a happy ending with The Bell Jar. And that’s okay.

Until next time,

Prof. Jeffrey

Recent Comments