“‘Where there is real love between people, as there was between all of us, then the details don’t matter. Love is more important than the flesh and blood facts of who gave birth to whom.'”

—from Birdsong by Sebastian Faulks

words to inspire before you expire

“‘Where there is real love between people, as there was between all of us, then the details don’t matter. Love is more important than the flesh and blood facts of who gave birth to whom.'”

—from Birdsong by Sebastian Faulks

” . . . Elizabeth was struck, not for the first time, by the thought that her life was entirely frivolous.

It was a rush and slither of trivial crises; of uncertain cash-flow, small triumphs, occasional sex and too many cigarettes; of missed deadlines that turned out not to matter; of arguments, new clothes, bursts of altruism and sincere resolutions to address the important things.”

—from Birdsong by Sebastian Faulks

“It seemed to Jack that if an ordinary human being, his own son, no one particular, could have this purity of mind, then perhaps, the isolated deeds of virtue at which people marveled in later life were not really isolated at all; perhaps they were the natural continuation of the innocent goodness that all people brought into the world at their birth. If this was true, then his fellow-human beings were not the rough, flawed creatures that most of them supposed. Their failings were not innate, but were the result of where they had gone wrong or been coarsened by their experiences; in their hearts they remained perfectible.”

—from Birdsong by Sebastian Faulks

Welcome back, class.

I’ve been back and forth on this one—there have been times when I couldn’t stand this play. But no matter if I like it or not, this Romeo and Juliet really deserves to be read by everyone, if only for the lesson it teaches—don’t let yourself be carried away by the passions of youth. That’s absolutely why we all read it in high school: so that our English teachers could remind us not to throw our lives away on “young love” and hurt others in the process.

Thankfully, the story is more than that—it is Shakespeare, after all.

It’s a story old as time—two teenagers, Romeo Montague and Juliet Capulet, become instantly infatuated with each other at first sight, even though their families are involved in an ongoing feud. They decide to get married, and in a complicated plot to get their families to stop fighting, Romeo kills a man and is banished, Juliet pretends to die to get away from her family, Romeo thinks Juliet is really dead and kills himself, and Juliet kills herself shortly after. Tragedy abounds.

It’s a story old as time—two teenagers, Romeo Montague and Juliet Capulet, become instantly infatuated with each other at first sight, even though their families are involved in an ongoing feud. They decide to get married, and in a complicated plot to get their families to stop fighting, Romeo kills a man and is banished, Juliet pretends to die to get away from her family, Romeo thinks Juliet is really dead and kills himself, and Juliet kills herself shortly after. Tragedy abounds.

People like to call Romeo and Juliet the greatest love story of all time, but the main characters are senseless, hasty, and melodramatic in their so-called love. It is an infatuation between two teenagers, built on feelings alone—not dependability, companionship, compatibility, rationality, or forethought.

Shakespeare makes them sound much less one-dimensional than my analysis, so the story is much better than that. His writing throughout Romeo and Juliet is romantic and beautiful, which helped Romeo and Juliet stand the test of time. But I also bet Shakespeare new exactly how dumb his main characters were, as they took their own lives for each other for the sake of what looked like love, but was actually a crush.

A Portrait of William Shakespeare

Shakespeare also gives his main characters a little credit when it comes to their families, which are pure chaos. The Montagues and Capulets are little more than rival gangs (hence the adaptation with a twist, the musical West Side Story), and they give Romeo and Juliet little choice but to marry in secret. Even the Friar that marries them has an ulterior motive—to unite the families through this marriage, end the feud, and stop the constant violence in the streets. The lesson to learn from Romeo and Juliet isn’t just for the children, but for the rest of the Montagues and Capulets that let passion guide their hearts towards violence.

That lesson—don’t let passion carry you away, for the sake of love, violence, etc.—is important in its own right, but I’ll admit it can diminish the story too. It’s easy to talk about Romeo and Juliet now, having read it almost 10 years ago, but no matter how much I made fun of it or hated reading it, it was one of the first real tragedies I’d ever read. The two main characters are partly at fault for their fate, but so are their families. This is a story about two people who committed suicide when there were so many other options available . . . all because they had dedicated their lives to a person they had known for less than a week. It’s infuriating and depressing, and a careful reminder of how far our reckless hearts can force us to go. In some twisted, backwards, cynical way, I think that makes Romeo and Juliet required reading for everyone.

Claire Danes and Leonardo DiCaprio in Romeo + Juliet (1996)

But if that’s not a good enough reason for you, I’ve got at least one more—Romeo and Juliet is everywhere. There are references to it in so many books, movies, TV shows, short stories, and poems that everyone deserves the chance to read it just to pick up on the subtleties of half of all art. Since teenagers with crushes is one of the most universal human stories in history, it’s applicable in every medium. On the list of the 50 Books alone, Romeo and Juliet is featured in one major form or another in Wuthering Heights, The Great Gatsby, Brave New World, The Way We Live Now, Huckleberry Finn . . . just to name a few. Romeo and Juliet pervaded the cultural landscape and staked it’s claim on teenagers with feelings, and everything that came after is a reflection of the original Shakespeare.

All in all, I may not like Romeo and Juliet all that much, but that makes it no less important. It deserves to be on the list of 50 Books to Read Before You Die, and there are several books worth kicking off to make room.

I’m finishing up Sebastian Faulks’ Birdsong, which I’ll write about next. Romeo and Juliet may be a better “love story,” but Birdsong is, in its way, a better story about love. There isn’t as much warning against runaway passion, but Birdsong seems more dedicated to the idea of love bringing people together, even in ways society looks down upon. Had Romeo and Juliet been stronger characters, it’s possible their long lives would have looked like the tortured lovers’ lives of Birdsong—but I’m getting ahead of myself. More on Birdsong next time.

Until then,

Prof. Jeffrey

“At first he thought the war could be fought and concluded swiftly in a traditional way. Then he watched the machine gunners pouring bullets into the lines of advancing German infantry as though there was no longer any value accorded to a mere human life. He saw half his platoon die under the shells of the enemy’s opening bombardment. He grew used to the sight and smell of torn human flesh. He watched the men harden to the mechanical slaughter. There seemed to him a great breach of nature which no one had the power to stop.”

—from Birdsong by Sebastian Faulks

“This is not a war, this is an exploration of how far men can be degraded.”

—from Birdsong by Sebastian Faulks

“None of these men would admit that what they saw and what they did were beyond the boundaries of human behavior. You would not believe, Jack thought, that the fellow with his cap pushed back, joking with his friend at the window of the butcher’s shop, had seen his other mate dying in a shell-hole, gas frothing in his lungs. No one told; and Jack too joined the unspoken conspiracy that all was well, that no natural order had been violated.”

—from Birdsong by Sebastian Faulks

Call me Prof. Jeffrey.

Call me Prof. Jeffrey.

Moby-Dick is one of the novels on the list that toes the line between too difficult for someone to enjoy and important enough to power through nonetheless. Most of the novels that fall into this trap are older works, like Dante’s Inferno or Don Quixote, both a bit too old and out-of-touch to enjoy outside of a class. Moby-Dick doesn’t do that though—its place in history recent enough that it doesn’t feel out-of-touch. Herman Melville actually makes plenty of genius moves with Moby-Dick that make it special even now, doing things that most novels today wouldn’t dare to do.

But it’s also a lot like James Joyce’s Ulysses—the novel is successfully doing so much that the end result is far too complicated. Of all the books on the list it’s probably most like The Count of Monte Cristo, in several ways—notably, both are tales of revenge where fate plays a big part. Melville makes sure to tell all sides of the epic tale he dreamed up, which makes the story thorough and way too long. It never fails to be interesting, though—I’ve learned more about whales and whaling than I ever wanted, and Melville did that without compromising on a story that was impressive to begin with.

Altogether, Moby-Dick seems near perfect; it may come off as long or tedious, but there’s no denying that all the pieces are in the right place for a story worth telling. That’s more than enough reason to read it before you die.

When I say I’ve learned plenty about whales, I mean it—the reason this novel is so long is because half of it is a textbook. The narrator, who calls himself Ishmael (and a questionable authority if there ever was one), spends most of his time making sure we understand exactly what our characters are facing . . . by describing any and all potentially necessary information about whales. He describes the body, behavior, history, and cultural impact of whales, along with details about whaling, oil, ocean life, the routines of the crew, and most importantly, the full description of Moby-Dick himself. As an example, one chapter is called “The Whiteness of the Whale,” which takes several pages to describe Moby-Dick’s rare white skin.

When I say I’ve learned plenty about whales, I mean it—the reason this novel is so long is because half of it is a textbook. The narrator, who calls himself Ishmael (and a questionable authority if there ever was one), spends most of his time making sure we understand exactly what our characters are facing . . . by describing any and all potentially necessary information about whales. He describes the body, behavior, history, and cultural impact of whales, along with details about whaling, oil, ocean life, the routines of the crew, and most importantly, the full description of Moby-Dick himself. As an example, one chapter is called “The Whiteness of the Whale,” which takes several pages to describe Moby-Dick’s rare white skin.

Reading Moby-Dick can be exhausting. Informative, too, but exhausting nonetheless. The monotony of the characters’ lives at sea is bleak and relentless, and the simplest action can be a reprieve from that monotony. In some chapters, nothing happens—except for a short essay on whales or whaling. These aren’t boring chapters—far from it. They are interesting and dynamic interjections, each one showing the reader something new about what’s to come or about the narrator’s mysterious inner thoughts. The takeaway is that these informative time-filler chapters—much like the book as a whole—are the essence of unconventional story-telling.

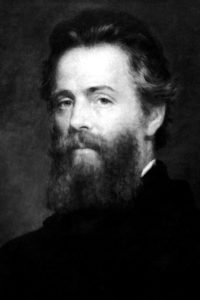

Author Herman Melville

The reason to pick up Moby-Dick off the shelf can be more easily found in two characters. One we already know—the questionable narrator, Ishmael, a passing soul in the larger narrative whose great purpose is to tell the story of the hunt for Moby-Dick. He lets us know early on that the whaling voyage is doomed, and he is the sole survivor of the ruined vessel. Because of Ishmael, most of the novel relies on concepts of fate and evil that are born from tragedy—every tension is in solving how the tragedy will happen, and every calm is subdued by the knowledge that disaster will strike soon enough.

Then there’s Captain Ahab—the obsessed, unstable, majestic, terrifying leader of the crew, most culpable in the ship’s demise and the resulting death of his crew. His arc is simple enough—Moby-Dick is responsible for Ahab losing his leg, and Ahab will sail to the ends of the earth and back on his quest of revenge to kill Moby-Dick for it. Ahab has a way of jumping off the page—he’s very human, malevolent, sarcastic, emotional, and liable to snap at any moment under the weight of his own obsession. Part of Melville’s genius is in making Ahab so many things at once that it’s hard to define him—he’s as complex as any realistic character, and just as much a legend as any character in the ancient epics of human history.

That being said, it’s just as hard to pin down what the novel really is, too. It isn’t a warning about obsession or revenge, though that seems to be an important idea. It’s definitely an epic, but it’s not a myth about an ancient legend—it’s about a whaling vessel, blown into epic proportions without losing an ounce of its careful realism (which is lacking in the myths of old). It’s not really an adventure story, though there’s adventure in it—along with too much foreboding and doom. More than a few chapters feature dramatizations or monologues, as though Melville is imitating Shakespeare. Parts of it even belong to comedy, or at least some kind of absurdism, such as it is—though it’s a bit hard to laugh knowing how it all ends.

One thing’s for sure: Moby-Dick is special. I know it’s not everyone’s cup of tea, so I do question its inclusion on the list, but there’s something special enough about it that everyone should at least consider reading it. It’s not just one of those important works of art—it’s a good and thoughtful story. Sometimes that’s all you need.

Next up, I’m finishing up Sebastian Faulks’ novel Birdsong—yet another I’d never heard of before starting the blog. More on that next time.

Until then,

Prof. Jeffrey

“At such times, under an abated sun; afloat all day upon smooth, slow heaving swells; seated in his boat, light as a birch canoe; and so sociably mixing with the soft waves themselves, that like hearthstone cats they purr against the gunwale; these are the times of dreamy quietude, when beholding the tranquil beauty and brilliancy of the ocean’s skin, one forgets the tiger heart that pants beneath it; and would not willingly remember, that this velvet paw but conceals a remorseless fang.”

—from Moby-Dick by Herman Melville

“There are certain queer times and occasions in this strange mixed affair we call life when a man takes this whole universe for a vast practical joke, though the wit thereof he but dimly discerns, and more than suspects that the joke is at nobody’s expense but his own.”

—from Moby-Dick by Herman Melville

© 2025 50 Books to Read Before You Die

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

Recent Comments