“The facts, if not true, were well invented; the arguments, if not logical, were seductive.”

—from The Way We Live Now by Anthony Trollope

words to inspire before you expire

“The facts, if not true, were well invented; the arguments, if not logical, were seductive.”

—from The Way We Live Now by Anthony Trollope

Good morning, class.

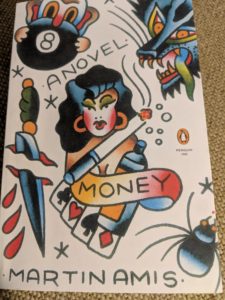

So . . . I’ll just come right out and say it: Money: A Suicide Note is one of my least favorite books of all time.

To read Martin Amis’ Money is to be met with a tour de force of alcoholism, drugs, addiction, rape, sexism, homophobia, manipulation, and toxic behavior the likes of which no one should have to endure. Money is a kaleidoscopic perspective on humanity’s fast and entertaining decay, due almost entirely to the concept of money and its poisonous fumes.

I will admit, there are parts I liked, or at least appreciated. And in theory, the book is a perfect criticism of celebrity lifestyle and capitalism. Money points out our inherent cultural flaw, our need for, dependence on, addiction to money—better than most books I’ve read on the subject. I have no doubt that that’s why this novel made the list.

But the details—the characters, plot, symbols, words—made me sick. It was crass and disgusting. Maybe I would have enjoyed it more if I had known what I was getting into (before seeing the list, I had never heard of Money before, so I went in cold); after all, I’ve seen movies and read books that aim to be offensive, and the best ones, like Money, have a clear and even moral purpose, like criticizing cultural flaws. Still, I’ve never enjoyed reading a book less, and I won’t get that time back.

But the least I can do is tell you who these unlikable characters are, and a bit about what they do that’s so unlikable. The narrator is a man named John Self, a conceited, sadistic, out-of-control addict attempting to adapt his story into a movie. He is surrounded by celebrities that are as self-absorbed as he is, as money-addicted and as morally bankrupt too. He spends his days in constant cycles of prostitutes, alcohol, smoking, and mindless purchases, and all the while he experiences a ceaseless and vulgar inner monologue that is as carefully crafted as it is offensive.

But the least I can do is tell you who these unlikable characters are, and a bit about what they do that’s so unlikable. The narrator is a man named John Self, a conceited, sadistic, out-of-control addict attempting to adapt his story into a movie. He is surrounded by celebrities that are as self-absorbed as he is, as money-addicted and as morally bankrupt too. He spends his days in constant cycles of prostitutes, alcohol, smoking, and mindless purchases, and all the while he experiences a ceaseless and vulgar inner monologue that is as carefully crafted as it is offensive.

John Self reminds me a lot of Holden Caulfield, the main character and narrator of The Catcher in the Rye. Caulfield is similarly problematic, with his intrusive and offensive thoughts filling up most of the novel; but I liked reading The Catcher in the Rye, and I know exactly why it was better. Caulfield was an angsty teenager, dealing with a lot of personal issues in the way a teenager might—lashing out at adults, behaving irrationally, refusing to face his issues head-on, etc. Even so, ultimately The Catcher in the Rye is about a search for happiness, and Holden’s care for younger children (and their untainted innocence) expresses that. Our focus on a an unlikable narrator becomes our focus on a teenager in crisis and on society’s mistreatment of children.

But Money doesn’t do that. John Self is a grown man, and spends a lot of time blaming his equally terrible father for his own mistakes, despite having the ability to change his ways. He has broad generalizations about the world and its mechanisms, and everything he says is questionable or flat-out immoral. He despises people that are different from him and he despises himself. He crosses the line from offensive to unforgivable far too often, in ways I don’t care to repeat. And unfortunately, he is on every page.

Author Martin Amis

Now, there are things that I like. For instance, its clear that Martin Amis knows what he’s doing—John Self’s diatribes are despicable, but well-written. The clever word choice and puns, the perfectly captured voice of John Self, the balance of the whole story from beginning to end . . . Amis is a craftsman.

Amis also happens to write himself into his own novel—a fun meta twist that uses “character-Martin-Amis” to help show what “writer-Martin-Amis” is trying to do. He gets to poke fun at his own pretentiousness and explain his actions for creating a character like John Self—it’s his way of putting all of the poison of fame and fortune into one tragic character, destroyed inside and out by the way we live now. The episodes with “character-Martin-Amis” stood out as Money‘s most creative and intriguing moments.

And yet, for all its technical brilliance, I can’t stand the novel’s content. Money‘s plot is weak, spending more time creatively caving in on itself than telling a story, which I could live with, except that whatever story is left is detestable. The thinness of the plot is paired with disgusting scene after disgusting scene—an endless episodic bombardment of debasement and degradation. I didn’t enjoy it and I’m glad it’s over now.

With that out of the way, I can look forward to the remaining books on the 50-books-list. I can’t guarantee I’ll enjoy what stories are left, but it’s a safe bet that Money is going to remain at the top of my I-hated-this-book list for quite some time, if not forever.

Next up, I’m finishing The Way We Live Now by Anthony Trollope—a novel that, so far, I have enjoyed. That’s more than I can say for some books.

Until next time,

Prof. Jeffrey

“If we all downed tools and joined hands for ten minutes and stopped believing in money, then money would no longer exist. We never will, of course. Maybe money is the great conspiracy, the great fiction. The great addiction too: we’re all addicted and we can’t break the habit now. There’s not even anything very twentieth century about it, except the disposition. You just can’t kick it, that junk, even if you want to. You can’t get the money monkey off your back.”

—from Money: A Suicide Note by Martin Amis

“Should the earth enter turnaround tomorrow, nuke out, commit suicide, then we’ll already have our suicide notes, pain notes, dolour bills—money is freedom. That’s true. But freedom is money. You still need money.”

—from Money: A Suicide Note by Martin Amis

“Money is the only thing we have in common. Dollar bills, pound notes, they’re just suicide notes. Money is a suicide note.”

—from Money: A Suicide Note by Martin Amis

Good morning, class.

I should tell you . . . I’m not always writing about what other people have written. I feel like I’m doing a good enough job reviewing the 50 Books to Read Before You Die (you’d tell me if I wasn’t, right?)—but my writing talents aren’t limited to book reviews. I’ve written my fair share of poetry, for instance, and a handful of those poems have even been published. And today, I’d like to lend a bit of credibility to my own writing—by sharing some poetry, of course!

I’ve picked three of my poems to share, with a bit of commentary for good measure. Enjoy!

Regarding musical thoughts . . . consider

The difference between thoughts and the ones who

Think them.

Through meticulous study, through

Expression, we thinkers rage and condemn

Stark thoughtlessness.

To impose on mayhem,

Order—that is our aim, our daily stress,

Our pang-laden dreamscape.

If we should guess,

God might be mayhem—leaves stretched in no shape

While we stand mean on wrathful roots.

That scrape,

Which our thoughts brace against the gentle fruits

Of our bodies and spirits, is music.

Consider the ravens—thoughtless and whole,

Scolding our scrape with their symphonic squall.

“Consider the Ravens” comes from a Bible passage, Luke 12:24, which can be boiled down do a pretty simple concept—birds don’t worry about anything and are fed nonetheless; you shouldn’t worry either. This verse always seemed to be aimed at me—the proof that I shouldn’t worry too much because God tells me everything will be alright. But worrying seems to be something the animal kingdom doesn’t suffer from all that often. Humans, on the other hand, worry all the time—it’s how we improve, how we change, how we challenge the status quo, and most importantly, how we make art, literature, and music. Our worry is what makes us seek perfection, and we’ll never reach it but never stop seeking it either, and that back and forth is sort of the secret to humanity.

I liked how this poem turned out, especially the rhyme scheme. This is a sonnet, but it’s been broken places that give it a different feel without becoming unbalanced. It looks like chaos, but it’s more like rearranged order, and I’m proud of that.

A Crack

And a faint Echo.

He Snaps the branches,

Here a hard wrist twisting and there a swift foot stomping,

With a surge of Crunch and Crackle—

Fingers careen down the bark, rough skin toppling twigs and leaves

That Clatter to the ground like debris.

Then, repetition:

Crack, Echo…

Snap, Crunch, Crackle, Clatter, Clatter—

Crack, Snap, Clatter,

Crack, Snap, Clatter.

He gathers, organizes, sets—

The overlapping wood,

The hodgepodge twig-pile,

The leaves, crushed and stuffed—

All in a cube—a prison of bark.

He isn’t alone—poking out of his pockets are the fire-starters of the unnatural world:

Old newspaper,

Weeks of collected dryer lint,

And the protruding metal stem of a blood-orange barbeque lighter.

There’s an accompanying Snap.

Another Snap.

Another Snap—and then a Crack, and a spark.

A flicker appears—a teardrop of light—

And it buds into two,

Produces four, reproduces eight,

And becomes a living flame,

While a column of smoke explores the air.

Lint catches, newspaper blackens, leaves curl, wood peels,

And the bark settles into its pit.

The light swims across his hard eyes

As he surveys his work—he is calculating, probing, observing, listening . . .

He protectively prods the creature with a leftover branch.

His eyes soften. His shoulders settle.

He interlaces his fingers and Cracks

The air out of his knucklebones.

Then he sits in his foldable chair

And settles his arm on my shoulders.

Sylvia Plath’s poetry had a tendency to take something ordinary and describe it so poetically that it seemed strange and foreign. That was my approach here, and though I don’t think it turned out that way, the result was something so simple and rustic that I fell in love with it. It’s a scene around a campfire; the wood is collected, the fire brought chaotically to life, and the fire settling into a dependable flame.

I applied some of the regular poetic tricks—the metaphor of the fire as alive, the implication that the man is creating a living thing (almost parent-like), the destruction of the first half building to the creation of the second half, etc. I’m particularly proud of the use of sound . . . I’m typically more of a visual/verbal guy, and this is my attempt at capturing the noises of the scene as much as the visuals. You’ll notice the sound is mostly at the beginning, before the light becomes a factor in the scene (oooooo . . . meaning!!)

I know a man as if from a strange dream. I know

His fervent voice, his sympathy, his charming face,

His internal adversity, and his true, whole

Story. Of few others can I claim such a bare

Knowledge; but my knowing is like a song I hear

In rare moments, when certainty guides my passion.

He wears a wooden mask, matching social passions

For etiquette’s sake—and with all I seem to know,

His mask, at times, fools even me. The voice I hear

Between the wooden lips of his fictitious face

Kindles in me an insobriety. I bear

It, if only to sense the more resonant whole.

I can sense harmony there, which resonates whole,

But seems built brutishly with divergent passions—

A series of conflicting fragments, never bare

But for the miracle of the harmony—no

One flaw exposed. This seemingly perfected face

Spoils any harmonic strain I would wish to hear.

But beyond these sounds is a voice I want to hear—

The voice of that man’s mind, trapped by the sullied whole

Of that harmonious character and that face

He shows the world. His mind speaks of different passions,

Of contrarian thoughts, of worlds I could not know,

And of dreams my spirit could only hope to bear.

Within the depths of such a hidden mind, he may bear

An ocean of knowledge, which deepens as it hears

The songs of others and swells as it comes to know

The strangeness of a senseless world, bursting with whole

Fragments of melodic, discordant compassion

That dares to flaunt itself at his fictitious face.

Beyond this hidden mind, and far beyond that face

Is, hopefully, some soul—a purity he bears

For entropy’s sake. This soul may guide his passions,

Divergent as they are, and may let his mind hear

Of love in the darkness we endure as a whole.

And beyond this soul dwells something no one could know . . .

. . . Perhaps some faceless, transparent eardrum that hears,

Perhaps, the whole human symphony, and that bears,

Perhaps, a passion for a man he hopes to know.

This one is more personal. There’s a man in my life who is hard to describe, but I used poetry and made an attempt—I left out the details and decided to describe my knowing him . . . the poem is less about the person and more about his closeness to me. He is a lot like me, and there’s a lot we know about each other, but the great obstacles of humanity keep us from knowing each other completely—I know him as he presents himself to me, but I don’t know his thoughts, his dreams, his soul . . . I can’t know those things. I can tell there are things about him that I can know, even without proof, because I like to think he is like me in that way—he wants to know me as much as I want to know him, and through that, we begin to know each other more deeply.

This poem is in the form of a sestina—a long and repetitive form that uses the last word in each line over and over again in different, predictable patterns. Using this form is a great way to tackle the kind of subject that is hard to convey in fewer words—the kind of subject that needs a variety of approaches in order to make sense, or that attempts to capture a concept in its totality, from all angles. It doubles back quite a bit, but I think it gets the point across, and of that I am happy.

I’m finishing up Martin Amis’ novel Money: A Suicide Note, so that’s what I’m writing about next. I’ll be honest, I am not at all thrilled by it—there’s a lot that makes it unlikable, uncomfortable, and unnecessary. I’ve got a few ideas about why it made the list, but I’m not sure that any of those reasons made it actually worth my time. In any case, I’ll try to write as unbiased a blog post about Money as possible.

Until then,

Prof. Jeffrey

“Sometimes I feel that life is passing me by, not slowly either, but with ropes of steam and spark-spattered wheels and a hoarse roar of power or terror. It’s passing, yet I’m the one who is doing all the moving. I’m not the station, I’m not the stop: I’m the train. I’m the train.”

—from Money: A Suicide Note by Martin Amis

“What is this state, seeing the difference between good and bad and choosing bad—or consenting to bad, okaying bad?”

—from Money: A Suicide Note by Martin Amis

“In the planetary aggregate of all life, there are many more suicide notes than there are suicides. They’re like poems in that respect, suicide notes: nearly everyone tries their hand at them at some time, with or without the talent. We all write them in our heads.”

—from Money: A Suicide Note by Martin Amis

Hello again, class.

Hello again, class.

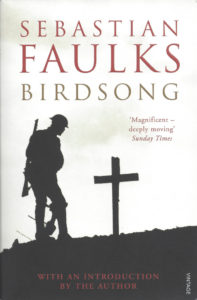

World War I and World War II are often lumped together as a collective global stain of history. They are so linked that WWII is usually seen as an extension of WWI, and it’s hard to talk about one without the other. It’s easy to forget that at the time, WWI was its own devastating conflict, worse than anything that had come before it and unimaginably tragic on its own.

That seems to be the driving motive behind author Sebastian Faulks’ novel Birdsong. In lumping together both World Wars, the identity of the first Great War gets lost in the past—Birdsong is about bringing that past to the forefront, lending focus to the social and cultural atmosphere at the time of WWI. The story is in its own way about uncovering history, using it to guide our present and plan our future while appreciating it for what it is, regardless of what happens next.

Poster for the stage adaptation of Birdsong (2010)

Faulks wouldn’t be able to accomplish this without a supportive story, and good characters to populate it. It’s safe to say that Stephen Wraysford is Birdsong‘s main character—he is a man with a complicated upbringing coupled with a melodramatic love affair in his early 20s, who is thrust into the Great War. His relationships with other men in the war help to humanize the conflict, though with all the violence he sees, he is always questioning humanity and its destiny. He seems fairly determined to hide his past, though he isn’t ashamed of it, and his love affair plays an important role in his future.

Fast-forward to the 1970s, where we meet a woman who is presumably his granddaughter—Elizabeth Benson, who shares some of the responsibility as main character. This 38-year old woman, having an affair of her own, is contemplating her place in life and decides to unearth her ancestral history. The novel jumps back and forth between Stephen’s perspective and Elizabeth’s, merging both points of view to appropriately assess the events of the war.

Author Sebastian Faulks

Birdsong is historical fiction—not a dramatization of real events. A based-on-a-true-story approach might have worked just as well for the sake of realism, but Faulks isn’t interested in detailing who did what where. He created fictional characters to fill them with the spirit of the people involved. Birdsong is a human drama, not a war epic or a nonfiction account—those things would be about the war itself, which is just another conflict in our history. Birdsong instead tells a story about individuals, who bear the weight of a larger catastrophe and question their place in it all.

If it were boiled down to one thing, Birdsong is a story about the best and worst of human nature. Stephen constantly asks himself how far the people in this war are willing to go, and nothing he sees lets him rest easy. But humanity has its moments of redemption in the way individuals treat each other: the way soldiers treat fellow soldiers, the way Stephen treats those he loves, and the way Elizabeth is able to find love amidst the war of her past. Humanity can be a cannibalistic hunger, a vain and selfish ambition that threatens its own existence, but it can also be warm and compassionate, full of love and hope. Birdsong makes the list for portraying humanity at its ugliest and at its most beautiful.

I liked reading Birdsong a lot, which has maybe contributed to my distaste for the next book on the list—a novel by Martin Amis called Money: A Suicide Note. I know why it made the list, but all the same I haven’t enjoyed it at all . . . but I’m getting ahead of myself. More on that next time.

Until then,

Prof. Jeffrey

© 2025 50 Books to Read Before You Die

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

Recent Comments