Welcome back, class.

Author Joseph Heller invented the phrase “catch-22”—in his novel, it’s a military rule for pilots: if a pilot shows signs of insanity, he doesn’t have to fly anymore combat missions; but if he asks not to fly anymore missions, he has proven his own sanity by being aware of the danger of his surroundings, and he is required to fly as many missions as the military requests; if he doesn’t ask to be grounded, and no one declares him insane or sends him home, he continues flying missions even though he might be insane and doesn’t have to, but as soon as he asks to be grounded, he has to fly more missions because he’s clearly sane.

If you feel like your mind is doing back flips, you’re in the right place. All of Catch-22 is like this—the “catch-22” rule is one of many self-defeating bureaucratic and social conundrums that keep soldiers fighting, whether they want to or not. Unlike Sebastian Faulks’ Birdsong, it’s not a series of brutally realistic battle scenes, side-by-side with meditations on inhumanity (at least, it’s not ONLY that); instead, Catch-22 is an absurdist comedy, proving just how insane war really is, and how insane people have to be to want to be a part of one.

There almost isn’t a main character, but the one we focus on most is Yossarian, a fighter pilot who’s true enemy seems to be the war itself. He finds creative ways of avoiding combat—most often, he’s in the hospital for an illness that he intentionally aggravates and pretends to continue suffering from. But his officers keep raising the number of missions pilots are required to fly, and his ticket home becomes more and more out of reach. Instead of having a kind of character arc, where he finds a way to accept the war or escape it, he ends up continually fighting against the war, battle after battle, and either Yossarian or the war will lose, or it will keep on going endlessly.

There almost isn’t a main character, but the one we focus on most is Yossarian, a fighter pilot who’s true enemy seems to be the war itself. He finds creative ways of avoiding combat—most often, he’s in the hospital for an illness that he intentionally aggravates and pretends to continue suffering from. But his officers keep raising the number of missions pilots are required to fly, and his ticket home becomes more and more out of reach. Instead of having a kind of character arc, where he finds a way to accept the war or escape it, he ends up continually fighting against the war, battle after battle, and either Yossarian or the war will lose, or it will keep on going endlessly.

The rest of the characters have a range of influence on Yossarian’s story, and each chapter is named after one of the characters in his life—fellow soldiers, superior officers, lovers, villains, and strangers he meets on his misadventures. The episodes in his life are told out of order, alternating between the present and the past so subtly that it can be hard to know when something is taking place. And one terrible event after another makes Yossarian’s life harder to protect, so that he’s more desperate to do whatever he can to save it.

The humor is warped and depraved—a not-so-subtle coping mechanism to deal with death around every corner, a mechanism that most 20th century soldiers, if not all, know very much about. This is self-defeatist comedy—comedy that points out how funny it is that the world works in such a ridiculous way, gently avoiding (or painfully reveling in) how terrible in all is. It’s cynical, uncomfortable, offensive, and nonetheless hilarious . . . that’s Heller’s genius, I think. Catch-22 is unlike any war novel I’ve ever read, because the intent is to point out, in the midst of the chaos, the rage, the terror of war, how insane it all is.

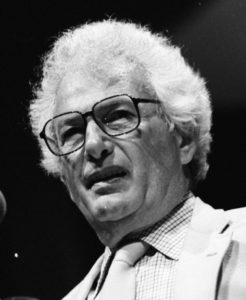

Author Joseph Heller

And for all that, Catch-22 is a messy story—and that’s a compliment. I’ve called it an “anti-story” before, because it breaks most of the rules of fiction. It’s not a linear story, and it wouldn’t be even if it was in chronological order. It’s more dialogue than exposition, and the dialogue is where most of the humor is, but it’s meant more to establish the environment of war than to tell a story. Yossarian doesn’t have an arc—he’s a desperate, determined man trying to survive, and that’s true on the first page and on the last. It’s all a mess, and most people don’t like it because of that.

And that’s exactly why it makes the list of books you should read before you die—it’s an anti-war anti-story, and nothing else I’ve ever read comes close to showing me how crazy war is, but that it’s the way of the world whether we like it or not. Yossarian seems like the crazy one because he wants to protect his own life, even as he’s criticized and penalized for refusing to die for his country. It’s a radical notion even today—that dying for your country is insane—and that makes Catch-22 one of the most important war novels from the past century.

Up next is a different kind of absurd—The Stranger by Albert Camus (referred to on the 50-books list as The Outsider—a translation discrepancy). Instead of laughing at the absurdity of it all, Camus seems to want readers to realize that nothing matters, and that’s that—much less entertaining, and much shorter, compared to Heller’s Catch-22, but just as important philosophically. What kind of life do we lead when nothing matters? More on that next time.

Until then,

Prof. Jeffrey

The book opens with a notice, explaining that anyone attempting to find motive, moral, or plot in this story will be subsequently prosecuted, banished, or shot. From the opening page, this book flaunts narrative, which is a hole-in-one from where I’m standing. The story that follows is a series of funny and dramatic events with a few well-developed and desperate characters and a barrage of side-character kooks to keep things light and interesting. It’s meant to be a delightful adventure story, through and through.

The book opens with a notice, explaining that anyone attempting to find motive, moral, or plot in this story will be subsequently prosecuted, banished, or shot. From the opening page, this book flaunts narrative, which is a hole-in-one from where I’m standing. The story that follows is a series of funny and dramatic events with a few well-developed and desperate characters and a barrage of side-character kooks to keep things light and interesting. It’s meant to be a delightful adventure story, through and through. But I’ve gotten ahead of myself—the only way this anti-narrative story even remotely works is because it has good characters. Huck is a boy in the American South, and he comes from an impoverished world with an abusive father. He views himself as a wrongdoer, or as trash, so he oscillates between wanting to do what’s right and giving up to do wrong. This puts him directly on the path of running away with an adult slave, Jim, whose relationship with Huck is tumultuous, subtle, carefree, and one of the strongest examples of friendship literature has to offer.

But I’ve gotten ahead of myself—the only way this anti-narrative story even remotely works is because it has good characters. Huck is a boy in the American South, and he comes from an impoverished world with an abusive father. He views himself as a wrongdoer, or as trash, so he oscillates between wanting to do what’s right and giving up to do wrong. This puts him directly on the path of running away with an adult slave, Jim, whose relationship with Huck is tumultuous, subtle, carefree, and one of the strongest examples of friendship literature has to offer.

Recent Comments