Hello again, class.

While it’s still Black History month, I want to do a little digging into one of the bright spots in literary history: the Harlem Renaissance. I am not an expert, but I know a little . . . enough to share my favorite writings from the period.

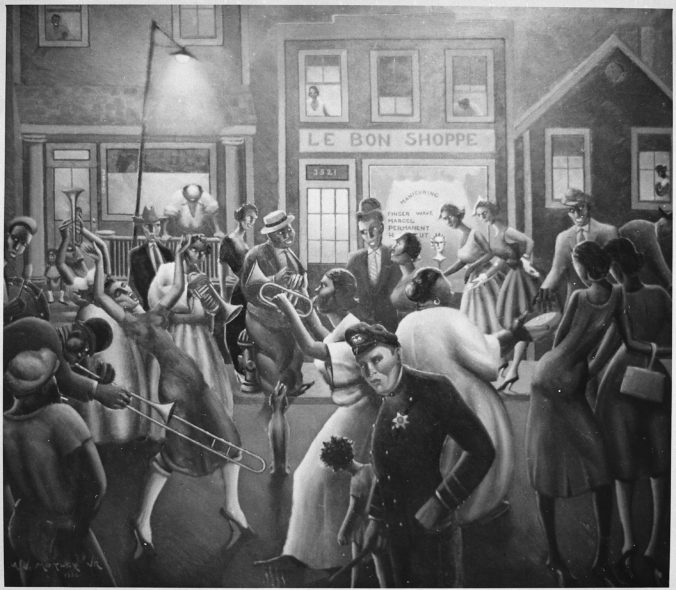

The Harlem Renaissance was an energized rebirth of African-American art and culture. After the Civil War and Reconstruction had dramatically changed (or tried to change) racial relationships in the South, there was a period called the Great Migration—a majority of the black population in America moved North. Within the walls of segregation, black Americans from all over the country began to culturally clash and grow with each other, churning out art, music, and literature.

From about 1917-1936, America’s black population caused a cultural explosion. The renaissance was the wildfire caused by the spark of the Civil War, as well as the prologue to the Civil Rights Movement and race relations in America throughout the 20th Century. And the literature—of which I’ve read a small percentage—is incredible.

I’ve made a list of my favorites (not the best, not the most important . . . just my favorites).

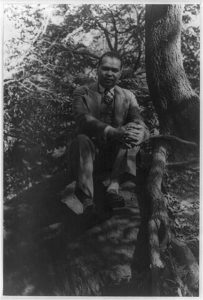

Poet Countee Cullen

- “Heritage” (Poem) by Countee Cullen: To sum up this poem, it’s about a black man struggling with the foreignness of his African heritage—he is an American, no matter how much America wants him to be African. He poetically describes stereotypical African imagery and culture, and it feels strange to him . . . a feeling both awkward and haunting. (Favorite Lines: “Spicy grove, cinnamon tree, What is Africa to me?“)

- “America” (Poem) by Langston Hughes: Few poets capture the dream of America as well as Hughes, and “America” does that and more. It is a celebration of the American melting pot, and the reputation America has had as the outcast whose arms are open to other outcasts. There is a critical tone, but it’s surrounded by hope for America’s future. (Favorite Lines: “You know me, Dream of my Dreams, I am America. I am America seeking the stars.”)

Author Langston Hughes

- “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain” (Essay) by Langston Hughes: This nonfiction piece about art and race is eye-opening, and I can only imagine how much it revolutionized a future for black artists at the time it was written. It talks about the systematic favoring of white people within the black community, and that the only way black artists can succeed is by being aware of—and subverting—that favoritism. (Favorite Lines: “But this is the mountain standing in the way of any true Negro art in America—this urge within the race toward whiteness, the desire to pour racial individuality into the mold of American standardization, and to be as little Negro and as much American as possible.”)

- “How It Feels to Be Colored Me” (Essay) by Zora Neale Hurston: Here is Hurston’s biographical essay about her coming to understand her race, in terms of skin color and culture. She beautifully describes her childhood discovery of her colored-ness, and where that belongs in her citizenship, her spirituality, her art, and her relationships. It is cataclysmically gorgeous. (Favorite Lines: “The cosmic Zora emerges. I belong to no race nor time. I am the eternal feminine with its string of beads.”)

Author Zora Neale Hurston

- Their Eyes Were Watching God (Novel) by Zora Neale Hurston: If I had read this more recently, I’d make a full post about it—as of now, I can’t do it justice, but it certainly belongs on the list. The novel tells the story of Janie Crawford and her three marriages, each of which inspire a journey of self-discovery. Janie’s journey is hard, and Hurston’s prose is beautiful. The novel is usually considered a result of the Harlem Renaissance, rather than a part of it, but it’s worth mentioning nonetheless. (Favorite Lines: “There is a basin in the mind where words float around on thought and thought on sound and sight. Then there is a depth of thought untouched by words, and deeper still a gulf of formless feelings untouched by thought.”)

For my sources, I used The Norton Anthology of American Literature (ed. Reidhead), The Portable Harlem Renaissance Reader (ed. Lewis), and a copy of Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God.

Let me know if there’s something else I should include . . . I’m always looking for recommendations!

Until next time,

Prof. Jeffrey

Recent Comments