Hello again, class.

This isn’t a review or a critique of Anne Frank’s Diary—that’s not something I would consider appropriate for a book like this. The private journal entries of a teenager are a certain kind of sacred. There are parts about her Diary I don’t like, but they are a part of Anne Frank’s tragically cut-short life and deserve to be cherished.

This isn’t a review or a critique of Anne Frank’s Diary—that’s not something I would consider appropriate for a book like this. The private journal entries of a teenager are a certain kind of sacred. There are parts about her Diary I don’t like, but they are a part of Anne Frank’s tragically cut-short life and deserve to be cherished.

The reason a book like this is published is not for something like literary merit or artistic value (though, miraculously, it has both anyway). The reason a book like this is published is to imprint the tragedies of history into the minds of as many people as possible, and to cherish the memory of a collective and personal loss. That also happens to be why it makes the list of 50 books to read before you die—not for the value of its content or structure, but for its universal need for recognition.

There is very little of the major story within the Diary, because that story happens mostly before and after Anne Frank’s writings—the text itself fills in the details of a story that’s already in place. I’m not taking any chances here—since we live in a world of Neo-Nazis, Holocaust deniers, and “fake news,” I’m going to recap the moments in history that The Diary of Anne Frank is a concrete part of.

Anne’s story is about a Jewish family that goes into hiding because of the Nazi regime, a radical political party, spreading from Germany. The Nazis declared that Jewish people were responsible for German failures in WWI and were an inferior race, leading to the hunt for and capture of Jewish people. What started as a political movement became the systematic racial genocide known today as the Holocaust.

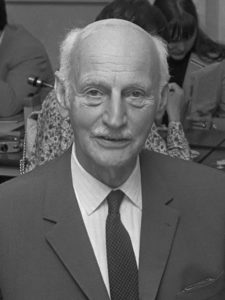

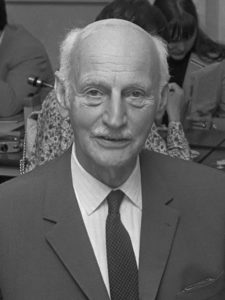

Otto Frank, Anne’s father (1968)

The Frank family hid in a small set of rooms behind a bookcase in a warehouse, along with four other individuals. They hid there successfully for two years, but before the end of WWII, the Franks were captured and sent to concentration camps. All but Anne’s father Otto died in these camps, and after regaining his freedom, he found the contents of his daughter’s diary. He decided to have the contents published.

The book serves as a reminder of the tragedy of the Holocaust and the very human lives lost to history, despite the inhumanity with which those lives were portrayed by the Nazi party.

Which brings us to the Diary. Anne gets the blank diary as a birthday present in 1942, and she begins writing her everyday thoughts and feelings. Not long after, the family goes into hiding—most of her writings are various forms of cabin fever from the perspective of a teenager, which is equal parts boring, frightening, and inspiring. Anne is an amazing writer and an insightful (though never unbiased) person. She seems to always write with a purpose and represents childhood and youth in her own way. Even when the entry is dull, the writing is not.

I review her writing (like I said I wouldn’t earlier) because it was purposefully well-written. She writes about being a writer and about a future in journalism, and the Diary has stood the test of time partly because she wrote so well. This diary was her chance to practice her craft, and her craft is worth reviewing. She writes about her feuds with those hiding with her, her desires for romance, her thoughts on humanity, her daily routine, and her fears and doubts. Reading her diary is watching her transform over the course of two years in hiding.

And then the Diary ends, unceremoniously. The inhabitants of the “Secret Annexe” (as it’s known in English) were captured in 1944, and the writings of a young girl were ignored and left behind. The nature of the book’s ending forces a return to the historical facts of the end of Anne’s life. You’re reading it knowing that eventually, she will die—and then the book ends as incompletely as her life. The ending reshapes the Diary back into a historical artifact, along with the reports of her life in the concentration camp and the details known of her death.

And then the Diary ends, unceremoniously. The inhabitants of the “Secret Annexe” (as it’s known in English) were captured in 1944, and the writings of a young girl were ignored and left behind. The nature of the book’s ending forces a return to the historical facts of the end of Anne’s life. You’re reading it knowing that eventually, she will die—and then the book ends as incompletely as her life. The ending reshapes the Diary back into a historical artifact, along with the reports of her life in the concentration camp and the details known of her death.

The Diary itself doesn’t tell the story of Anne’s life as much as it reflects the vignettes that make up her experience—that of a teenager in hiding (which is special enough). But the statistics of her life and death, while telling a story, are heartless. Anne’s humanity is more alive in her own writing, which gives a voice to the millions of victims of the Holocaust that could only tell stories with the statistics of their lives and deaths. The picture on the cover of The Diary of Anne Frank becomes the face of this period in history.

And as important as that is, it tends to limit all that the Diary can be. The reason to pick up the Diary and start reading is because it represents one of the darkest moments in human history, and the book itself has a tendency to belong to that part of history. But it isn’t as dark as that—this book is one of the bright spots in an era of horror. The reason to continue reading it, once you’ve picked it up, isn’t to remember the Holocaust or the death of a child. The reason to continue reading it is to witness the unabridged beauty of a young girl’s voice.

The time I have put in to reading these books and writing these posts can feel unnecessary at times. Some of the books I’ve trudged through have felt like a bit of a waste. But The Diary of Anne Frank is one of those that restored me—I read it once in seventh grade, and it left very little impact at the time, so I’ve been willing to chalk it up as nothing more than an important piece of history. But reading it again helped me realize what I missed, and how important was. I’m happy I read it, and I’m happier I read it a second time.

Next up, I’m jumping backwards to read Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift. I’ve always liked the story for exactly what it is, even if it was never that special to me, but its effects can be seen everywhere in our society today. I’m excited about diving into it again.

Until then,

Prof. Jeffrey

This isn’t a review or a critique of Anne Frank’s Diary—that’s not something I would consider appropriate for a book like this. The private journal entries of a teenager are a certain kind of sacred. There are parts about her Diary I don’t like, but they are a part of Anne Frank’s tragically cut-short life and deserve to be cherished.

This isn’t a review or a critique of Anne Frank’s Diary—that’s not something I would consider appropriate for a book like this. The private journal entries of a teenager are a certain kind of sacred. There are parts about her Diary I don’t like, but they are a part of Anne Frank’s tragically cut-short life and deserve to be cherished.

And then the Diary ends, unceremoniously. The inhabitants of the “Secret Annexe” (as it’s known in English) were captured in 1944, and the writings of a young girl were ignored and left behind. The nature of the book’s ending forces a return to the historical facts of the end of Anne’s life. You’re reading it knowing that eventually, she will die—and then the book ends as incompletely as her life. The ending reshapes the Diary back into a historical artifact, along with the reports of her life in the concentration camp and the details known of her death.

And then the Diary ends, unceremoniously. The inhabitants of the “Secret Annexe” (as it’s known in English) were captured in 1944, and the writings of a young girl were ignored and left behind. The nature of the book’s ending forces a return to the historical facts of the end of Anne’s life. You’re reading it knowing that eventually, she will die—and then the book ends as incompletely as her life. The ending reshapes the Diary back into a historical artifact, along with the reports of her life in the concentration camp and the details known of her death.

Recent Comments