Good morning, class.

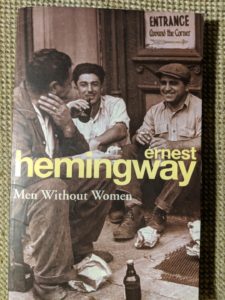

After reading Hemingway’s short story collection Men Without Women, I’m revisiting my previous list of favorite short stories and adding some more. Consider this list an addendum, for a total of 13 short stories that I just enjoy, through and through. You’ll notice they’re in chronological order; just my way of having fun.

James Joyce’s short story collection Dubliners, featuring both “Araby” and “The Dead.”

- “Araby” by James Joyce: Of course James Joyce makes the list again! “Araby” is a short and simple story from Joyce’s collection Dubliners—barely a featurette on a young boy with a first crush. The boy wants to buy a girl something nice at the nearby Araby festival, but his uncle keeps him from getting to the festival in time; he arrives at the festival too late, and he leaves without buying anything, hurt and upset by his uncle’s carelessness and his failure to make the girl happy. The emotions through the story aren’t complicated, but they are pure and childlike, stinging in all the right places—it’s a familiar story, and Joyce tells it amazingly well.

- “In the Penal Colony” by Franz Kafka: Kafka’s novel The Metamorphosis is the tip of the Kafka-iceberg—“In the Penal Colony” is just as twisted, tense, and tragic as The Metamorphosis. An unnamed traveler visits the execution grounds of a foreign land, where the executioner shows off an extravagant contraption used to kill criminals in the most just way possible (according to the executioner). The traveler knows that the contraption is inhumane, and the methods used to carry out executions are unethical—he debates whether or not to bring up his concerns as a foreigner, while the executioner describes the machine in detail. Once the traveler speaks his mind, though, the executioner makes a final decision about his machine, leading to a disturbing and dreadful climax that I won’t spoil here. It’s one of those stories that chills to the bone, while still being thoughtful and enlightening.

- “Big Two-Hearted River” by Ernest Hemingway: I have mixed feelings about Ernest Hemingway (like I mentioned on my Men Without Women post), but this is a Hemingway story I love. “Big Two-Hearted River” didn’t appear in Men Without Women, but it left its mark when I read it the first time six years ago. The main character, Nick Adams—a recurring character in several Hemingway stories—goes on a camping trip, making subtle references to the war he fought in and the trauma he’s suffered. It’s not a very exciting story, but it’s emotional and meaningful in Hemingway’s special way. I don’t see it mentioned often on lists of Hemingway’s best short stories, but I can say for sure that it’s my personal favorite of his.

Joyce Carol Oates, author of “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?”

- “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” by Joyce Carol Oates: Another chill-to-the-bone story, about a girl in a terrifying position with an older man. The girl, Connie, is the youngest in her family and seems to be the disappointing daughter, with flirty behavior and little responsible thinking. But the action of the story builds when a smooth-talking stranger who calls himself Arnold Friend comes to her house, and she’s alone. She carries on a conversation with him but keeps him at bay, until she realizes that things aren’t what they seem with this man at all. Most of the story is this conversation, and Oates writes the story with a kind of narrative science—everything is balanced and thought-out, with a million and one symbols, references, codes, and secrets hidden in the story’s details to fill English-class essays for decades.

- “Entropy” by Thomas Pynchon: Speaking of narrative science, “Entropy” is more a scientific narrative—a story that studies and responds to the scientific theories on Pynchon’s mind, specifically that of the heat-death of the universe and the deterioration of everything into chaos. Pynchon focuses us on a party that has been in motion almost two full days by the story’s opening, and won’t be stopping soon. Various scenes take place at this party—discussions on ongoing and ending relationships, games played, songs sung, alcohol abounding, and even an almost-drowning by a girl in a bathtub. People have existential conversations about language and meaninglessness while the party rages out of control, into the chaos the title hints at. It’s experimental and conceptual, and as a work of art always gets to exist beyond itself—breaking and redefining rules like few stories can.

ZZ Packer, author of “Drinking Coffee Elsewhere.”

- “Drinking Coffee Elsewhere” by ZZ Packer: This story doesn’t quite fit in with the rest on my list, if only because it tells a very contemporary story. It focuses on Dina, a new student at college, who is isolated, obstinate, passive-aggressive, and a red flag for every authority figure and potential friend that meets her. She strikes a teetering relationship with a girl named Heidi, which blossoms into a sexual awakening and—as her therapist claims—an identity crisis. Dina is in denial about plenty of things, not just with her sexuality and how it affects her identity, and it makes her one of the most interesting characters in any story. Through the hints and nods ZZ Packer sets up, we get to learn more about Dina than Heidi or her therapist ever could. It helps that this is one of the funniest short stories I’ve ever read—most of my favorites are downers, and this one is no exception, but it’s funny all the way down.

So there’s my list! Next up, you’ll see my review of Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Until then,

Prof. Jeffrey

Welcome back class.

Welcome back class.

Recent Comments