Hello again, class! Time to poetry it up again.

Be sure to check out my other favorite poems with Part 1 and Part 2 of this list. I’ve included links to each poem so you can read them for yourself!

- “If—“ by Rudyard Kipling

Kipling isn’t one of my favorite writers, but this is certainly one of my favorite poems. It’s built on a series of almost-impossible virtues, with the father-son relationship tagged on for good measure. The poem as a whole paints the perfect ideal to strive for, and I love it.

My favorite lines are “If you can dream—and not make dreams your master; If you can think—and not make thoughts your aim.” It always reminds me that my introverted delights should have a purpose, even if they aren’t clear to begin with.

- “The Road Not Taken” by Robert Frost

I think that “The Road Not Taken” has more depth than most people give it credit for. There’s the comparison between the two roads, one slightly more worn than the other, but both inviting and undisturbed. I like the speaker’s internal conflict about which road to take.

But it’s the last lines that keep this poem universal: “Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—I took the one less traveled by, and that has made all the difference.” Frost made good poetry, and “The Road Not Taken” is one of his best.

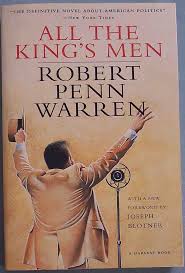

- “Evening Hawk” by Robert Penn Warren

This is one of the weirdest poems I’ve ever read. The word choice gets to me every time I read it—“angularity,” “avalanche,” “guttural,” “hieroglyphics” . . . and the image of a hawk’s wings as scythes cutting down stalks of time to describe the passing of a day is beyond creative.

If there’s anything this poem does wrong, it’s overreaching—poetry for poetry’s sake, one step too far. But for me, before reading “Evening Hawk,” poetry was flowers and love metaphors. This is one of the few early poems in my life that changed the game forever.

- “The Red Wheelbarrow” by William Carlos Williams

If “Evening Hawk” is one of the weirdest poems ever, then “The Red Wheelbarrow” is one of the simplest. It’s one of those that’s simple enough for anyone to read, understand, and analyze, but it’s also complete and complex enough to have layers of meaning.

It’s about the length of a sentence—four stanzas of four words each, painting a brief picture of a wheelbarrow. But if you look closely enough, you see the balance of each phrase, the care in each word, the imagery and the symbolism between the lines. It makes me smile and wonder every time I read it.

- “The Hollow Men” by T. S. Eliot

This Heart of Darkness-inspired poem (blog post pending for that novel) is classic T. S. Eliot—too vague to make complete sense but just beautiful enough so that sense doesn’t matter.

I like Eliot’s artistic choices, and it’s hard to like his work otherwise if you don’t, but it’s not hard to appreciate how powerful his poetry is. “The Hollow Men” showcases the best that modernism is known for—rule-breaking poetry, terror at the collapse of the old world, and a hodgepodge of genre that clashes against itself. It’s pretentious, but incredible.

- “The Names” by Billy Collins

This poem is dedicated to victims of 9/11, and for that alone it speaks volumes. Collins picks the names of individuals who died on 9/11, one name for every letter of the alphabet (though he asks us to “let X stand, if it can, for the ones unfound”). Those names haunt him—or maybe it’s less violent than a haunting . . . it’s more like the names are painted on everything he sees: the rain, the night sky, the shop windows, the bridges and tunnels of the city, and the petals of a flower. It’s a literary memorial; those names, and the lives that they belonged to, remain after the tragedy. Like I said, it speaks volumes.

- “Hate Poem” by Julie Sheehan

Of all of the poems I’ve selected (between all three posts) this one is the funniest. Sheehan wrote the exact opposite of a love poem—there was nothing else to call it but “Hate Poem.” She REALLY hates the subject of the poem. Everything about her hates the other person, from the flick of her wrist to the lint under her toenail to the “goldfish of her genius.”

What’s really remarkable is how beautiful the writing is, which is maybe even because of it’s content—it’s full of passion and exquisite hatred, and it’s one of the most enjoyable poems that’s ever crossed my path.

I’m not planning on a Part 4, but at this point, who knows what’ll happen.

Next up, I’m finishing up The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath. Also by Sylvia Plath, the poem “Lady Lazarus” (found on my Part 2 poetry list) equally deals in the subject of suicide. “Lady Lazarus” and other poems by Plath have a sense of glorifying suicide and death, which certainly makes me uncomfortable, but The Bell Jar seems to be more interested in portraying than glorifying. I don’t think her poetry is better or worse than her novel, but they are absolutely worth comparing, especially since they are eerily close to Plath’s real life suicide attempts and eventual suicide. But more on that next time.

Prof. Jeffrey

Tis’ the season, class.

Tis’ the season, class.

Recent Comments