Good morning, class.

I remember reading The Crucible in 10th grade. It didn’t change my life, but it felt important—it crossed my mind that in a younger grade or an easier class, this kind of story wouldn’t have been allowed. Before this, the hardest thing I’d ever read was Romeo and Juliet, which may seem difficult to a high school student but is simple in retrospect. I was finally getting to the thought-provoking stuff with The Crucible. I was being trusted with something more challenging.

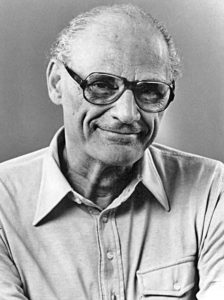

For all the reasons I like it, I have one major criticism: it’s about as subtle as cannon fire. In Arthur Miller’s defense, The Crucible was a direct response to the McCarthyism Era of the 1950s, where the slightest associations with communism could result in unfair trials and defamation—subtlety didn’t abound. The overwhelming panic of the time inspired Miller’s portrayal of the Salem witch trials, where a similar series of baseless claims led to the torture and death of innocent lives. Miller wanted to show America that panic can do irreparable harm to society, especially when we give in to it.

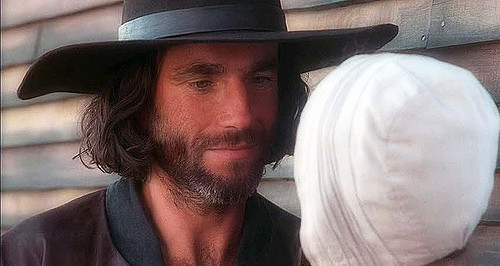

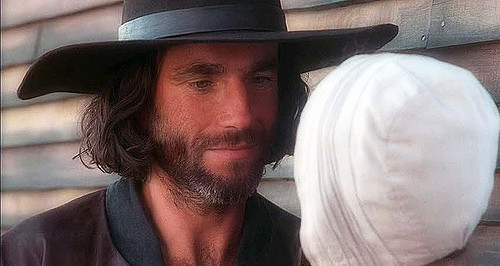

John Proctor, as portrayed by Daniel Day-Lewis in The Crucible (1996)

For students not in-the-know: the story mostly follows John Proctor, a man in a struggling marriage who despises hypocrisy, and Abigail Williams, who’s had an affair with John and becomes the spark that starts the witch trials. Abigail is clever: she uses the Puritan leadership’s fear of Satan and witchcraft to manipulate life in Salem, and encourages other girls to do the same. Abigail wants to get rid of John’s wife so that she can have him for herself, and her lies fool most of the town into thinking the Devil has his eyes fixed on Salem.

My favorite scene of the play is at the end of Act 3—after a poorly placed lie in the courtroom, an opportunity opens up for Abigail to give the performance of a lifetime. She pretends to see a bird, the shape-shifted form of a the little girl Mary (who betrayed Abigail by trying to come clean about everything). The bird Abigail “sees” begins to attack her and the girls on her side. The presiding judge eats up every word and every gesture, eventually convinced that they are under the thrall of Mary’s witchcraft. John tries to make the judge see reason, and Mary and the girls turn their attention on him, claiming that he is allied with the Devil. John gives up completely—he shouts that God is dead and that he and the judge will burn together in the end. It’s one of the tensest moments in literature I’ve ever read.

As far as characters go, Abigail is pretty simple—she wants John and finds a way to get him, with consequences she couldn’t have imagined. John’s arc is more interesting. He torments himself for betraying his wife, and both Abigail’s antics and the town’s response to them are eating away at his faith. John struggles to understand if he’s good or not; was his lust a mistake of immorality, or was it indicative of an evil he can’t help but succumb to? John’s doubt in himself makes it easier to trust him, in spite of his flaws, and that doubt is nowhere to be found in Abigail—her lack of doubt makes her determination terrifying.

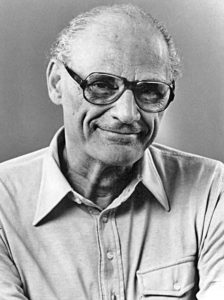

Playwright Arthur Miller

But the real difference between Abigail and John—and the extremes they represent—is the ability to confess falsely. Abigail’s sway over the town came from a confession people wanted to hear, and she gave it gladly. Her lies from that point grow and explode on the town. John’s resistance against these lies make him one of the only sane people left in Salem. Even his own true confession about the affair with Abigail falls flat against her lies—in Salem, lies seem to speak more truth than the truth does.

Everyone else in the story exists between these extremes—they are willing to lie, or believe lies, for their own sake. Sometimes, they’re sympathetic—anyone will confess if there’s enough pressure, which makes John that much more of a hero. In other cases, when a character is lying for their own gain, destroying the town as they go, it’s easy to wonder whether or not Satan did have a hold on Salem.

Historical accuracy is worth noting—Miller made some deliberate changes, the most significant being Abigail’s age raised to make her a more malevolent antagonist. He also removed a lot of extra people (for example, there were more girls and judges in the scene I described), if for no other reason than to make it more feasible on stage. Miller takes some liberties, but they’re in the name of his message—again, not subtle—that panic has the ability to destroy society, if we let it. I don’t know of another story that portrays panic so well, without it being a pale imitation of this, which is why The Crucible should have made the list.

I’m just finishing up The Count of Monte Cristo, so that’s on the agenda for next class. I’m realizing that the protagonist, Edmond Dantès, is heroic for the exact opposite reason as John Proctor—Dantès’ conviction makes him a force to be reckoned with against those who ruined his life. He has no doubt that his aims are governed by God, and that he is a divine tool in God’s works. Just goes to show you how widely stories can vary.

Prof. Jeffrey

Recent Comments